Beirut: After the Dust Settles with Christele Harrouk + Salim Rouhana

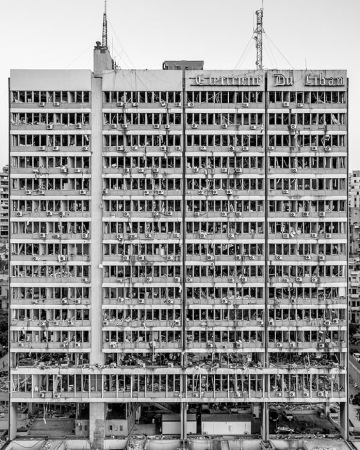

We are taking on the devastating Beirut explosion with two of the city's natives. They will share their perspectives on what rebuilding the city of Beirut could look like after such an unbelievable event. Photo courtesy of Rami Rizk.

"It only took a couple of seconds to destroy 40% of the city of Beirut on August 4th, 2020. A couple of trivial seconds were enough to determine the fate of the urban and social fabric of the Lebanese capital and its architectural heritage. Years and years of accumulated cultural assets fell instantly in distress, causing more harm than the infamous 15-year civil war. These seconds have erased the past, present, and destroyed future aspirations."

Those are words taken from Christele Harrouk’s article published in ArchDaily just one month after Beirut, the capital of Lebanon, sustained two catastrophic blasts that left the northern side of the city in ruins, just 6 months ago.

Listen to Christele Harrouk + Salim Rouhana on Design and the City:

First, we have the author of that article, titled Beirut: Between a Threatened Architectural Heritage and a Traumatized Collective Memory, from ArchDaily. Her name is Christele Harrouk and the description of the devastation captures the shock the city experienced--a shock that followed the country’s economic collapse atop a global pandemic.

Christele is a Beirut native, writer, managing editor at ArchDaily as well as an architect and urban planner who uses her expertise to address issues of the world through a contextual and architectural lens. Some of our long-time supporters and listeners might recognize her from our very first episode, in which she interviewed Thomas Heatherwick at the 2019 reSITE conference.

Alexandra Siebenthal, reSITE: Hi there Christele! Thanks so much for joining us, we’re honored to have you as a guest this time! Would you mind sharing a bit about yourself and your background?

Christele Harrouk, ArchDaily: Hi, Alex, I'm very happy to be again with you. So my name is Christele Harrouk. I'm an architect and urban designer, and the managing editor of ArchDaily. I'm Lebanese, I'm French, and I'm based in Beirut. And from this tiny capital, I reach the world through my work in the biggest architecture platform. So I focus a lot on cities and my writings and on the pressing issues that the world is facing. And those [I] will try to highlight the role of women in the creative field.

Alexandra: That’s great. So, as an urban designer and architect, how did you end up as a writer and now, managing editor at ArchDaily? Congrats on the new position, by the way.

Christele Harrouk: Thank you. So to be honest, I have always been into writing, you know, I've done it without giving it too much thinking. During my architectural studies, I used to use this approach to express my creativity and to reflect on subjects.

And, after I graduated, I contributed to a local architectural magazine for almost six years before I ended up at ArchDaily. So, I started as a content editor, and then as a senior editor, and now I'm the managing editor. So being multidisciplinary in today's world is essential, I think. And you think it's also important to embrace the different aspects of your personality, like whatever makes you who you are, and not fit into like these traditional boxes that you are so used to. So, in a way, I was able to put together both of my passions, writing and architecture, both equally creative for me and equally challenging. So there isn't one without the other, I suppose.

Alexandra: That’s beautiful. I think that sort of multidisciplinary approach is quite helpful in the arena of city-making. As an architect, what is it you love the most about Beirut?

Christele: You know, it's like one of the hardest questions to answer. Like, I don't know, it's hard to explain what I like about the truth. And sometimes I can't help but think that this is maybe part of why I like it. Like I could never figure it out. It's like, I don't know if it's a question of vitality. The city is always animated loud, vibrant, like literally at any hour of the day.

The only thing that I know and I'm sure of is that Beirut makes me feel alive.

"Beirut is technically the smell of the sun, sea, smoke and lemons"--this is a quote by Mahmoud Darwish that I love--I find it super genuine. Beirut has this charming chaos, crazy tastes, mood swings, noises, like it's literally everything and it has it all. And for me also Beirut is the people that warmth, their passion. It's such a flamboyant city, I don't really know how to explain it. It's all of this and so much more. And I don't think you can grasp the idea of Beirut if you didn't come here. And the only thing that I know and I'm sure of is that Beirut makes me feel alive.

Alexandra: You wrote a pretty powerful piece in ArchDaily that was published about a month after the blast. It provided an intimate look into that moment and I really felt like I was there with you; I felt that collective pain, but I also felt your passion for the city shine through. Could you tell us about how this moment played out for you? Where were you? What was your initial reaction?

Christele: Of course, so I actually had just returned home from a meeting in Beirut. I live in the suburbs, it's like 15 minutes away from the capitol. And I was on a zoom call with the whole team at ArchDaily when it happened. So technically, every Tuesday we have our usual content meeting. And we're like 20+ people talking. And as we were discussing stuff, all of a sudden, I saw one of my colleagues, Hannah, she lives in one of those high rises in Beirut. She's the second girl in ArchDaily that works here [in Beirut]. And Lebanon, I see her going under the table, hiding her head. And I was like, just like looking at her face, like what was happening. And then I heard the first explosion.

On that day, I literally called everyone I knew to make sure that we're safe. So imagine you have to call every single person, you know, everyone I ever met in my life. And everyone else was also doing the same.

And, of course, I didn't know what it was, at the time, I didn't understand anything, like the whole house moved, and I was so confused. And then the second sound was so much bigger. And at that time, I seriously thought that we were under attack, and that this was the end at some point. So the internet interconnection broke phone signals, also, like you couldn't call or reach anyone. I just wanted to know what was happening. And I didn't know that at the time, because like, there was nothing. So I went to the windows, and saw everyone on the streets. Also, everyone was like looking super confused, asking each other what happened, trying to make sense of it.

We had no idea because we were far and we were not in sight of the capital. So we had some damages, but very minor. Like at least 10 minutes passed before [news] started pouring [out]. And, we knew what happened to Beirut. We were not sure we knew that there was an explosion, but we didn't know what caused it at the time.

On that day, I literally called everyone I knew to make sure that we're safe. So imagine you have to call every single person, you know, everyone I ever met in my life. And everyone else was also doing the same. I was receiving random calls from people I barely talked to, just to make sure that I was alive.

Alexandra: Wow. You were definitely the first person we thought of when we saw that. That sounds like you lived a nightmare.

Christele: You have no idea how many emails I have received from like, people that I work with that I talked to online, asking me about this.

Alexandra: Yeah, I can’t imagine. It’s shocking. When you looked out your window what could you see? Could you see any smoke or make sense of anything that happened?

Christele: Like, I could see smoke from where I am, because like Beirut is on the sea. And I'm also on the coast. And Beirut is like this, like a kind of a semi-island. It goes out of the shoreline. And I could see like the smoke. But I had no idea what was going on. And like I didn't know, I thought we were really under attack. And I was like, 'who's attacking us?!' What's happening? At some point, I thought it was an earthquake and something huge fell. I thought about different scenarios, but I didn't even think for a second that this kind of explosion has happened and this kind of damage also.

Alexandra: Can you tell us about the extent of the destruction?

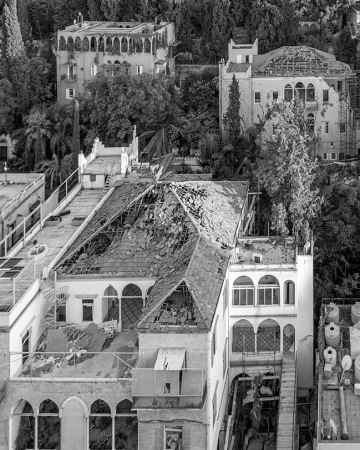

Christele: Yeah, as I said in the article, like 40% of the city was destroyed, because of these two explosions on August 4 the only numbers I have are the ones from the preliminary reports that stated that there was like around 200,000 housing units affected, 40,000 buildings damaged, 3,000 of which were like severely struck. We had 730 historical structures--the ones dating back to the 19th century harmed. 331 in despair and at risk of collapsing, and that's a huge number for a very small country like Lebanon.

So when I actually went on the ground the second day, that amount of destruction was unbelievable. People are even saying that even during 15 years of civil war, they haven't witnessed this much devastation. Literally, buildings were glassless, the city was glassless, and it was so sad that you could feel as if the city had lost part of its soul with this glass. It was kind of soulless.

And really, you cannot imagine the quantity of shattered and crushed glass cladding, wood, metal and aluminum elements on the street. It was really an apocalyptic scene, like one of those apocalyptic movies, exactly. So that's of course for talking about architecture. But you also have like infrastructural damages, economic damages, social, etc.

Alexandra: At a critical time for Lebanon, and for Beirut in particular, this really came as a crippling blow. I understand that the blast occurred in the cultural hub of the city; can you tell us about the neighborhoods which were most affected?

Christele: Of course. So the main shaken neighborhoods are the ones that were directly facing the port like in Medawar, Rmeil, Gemmayzeh, Achrafieh, Mar Mikhael, Karantina and Geitawi. So these areas have the old, the new, the poor, and the rich, they have it all, you know, they had a mixture of Ottoman, French mandate, modern, post-war structures, like everything was in there. And the first actually to receive the shockwaves from the blast, were the post-modern structures, the contemporary structures, I would say, that are facing the port directly. They were stripped down completely from their non-structural elements.

Everyone drank in Mar Mikhael, had their first kiss on the stairs of Gemmayzeh, worked in Ashrafieh, partied in Karantina, went to school in Geitawi, had their grandparents living in Rmeil—a big part of Beirut was in these particular neighborhoods, and losing them meant losing part of us.

Also, these areas have a lot of restored architecture gems, like the Sursock Palace and the [National] Museum, etc. It’s a very rich area. More than the architectural heritage, these neighborhoods were part of everyone’s memory and experience--and this is why it was also so devastating.

Of course, part of mine too. Everyone drank in Mar Mikhael, had their first kiss on the stairs of Gemmayzeh, worked in Ashrafieh, partied in Karantina, went to school in Geitawi, had their grandparents living in Rmeil etc. A big part of Beirut was in these particular neighborhoods, and losing them meant losing part of us. That part that kept us holding onto this country and holding onto Beirut. They were a hope for a better future.

Alexandra: That's devastating. There is certainly a fair amount of grief that follows such a loss. At this point in time, what does the city look like? How have people handled it, how have they carried on?

Christele: Well, you know, that since day one, like, people were mobilized, people we're trying to do something about, they're going to the streets helping each other, etc. So, there's a lot of initiatives, but they're initially like, they're initiated by people, and then not governments. So you have like, a lot of re-construction work going on. But of course, these reconstruction works are like, very punctual on certain houses, etc. Because, if you don't have these huge funds that are actually restoring a whole city. So, Beirut after three months is like the same thing, just cleaner, I would say. The streets are clean from the debris that was there. A lot of people have returned to their houses, of course, because of private initiatives or NGOs and organizations. But it's still a very sad apocalyptic scene at night.

A city is a mere reflection of its inhabitants

Alexandra: Wow. Yeah, it's, it's pretty unbelievable. So you said in your ArchDaily piece, “we get the city we deserve”. Can you maybe talk more about what that means for you?

Christele: Well, I always say that a city is a mere reflection of its inhabitants. So when I said we get the city we deserve, I wanted to have a provocative statement in a way, especially in the context of Beirut. I used it because I wanted everyone to question their actions and to reevaluate the situation and to think again—is this what they deserve? Like by saying this, I'm making everyone who is reading the article, especially, Lebanese people think, ‘wait, is this what we deserve’?

So at the end of the day, cities don't exist without people, and governments are formed by people. So it's a way for me to make them rethink stuff and make them like in a way also think about the power that they hold, because the power is always in people's hands. And like about that, I would also want to add that political regimes come and go, but cities are here to stay. So for me, it was kind of a wake up call, or for me it was, I had to wake other people.

So at the end of the day, cities don't exist without people, and governments are formed by people.

Alexandra: I think this commentary strikes a familiar chord for many cities and their inhabitants and it's a sentiment I can relate to, given a lot of current events and their general atmosphere.

Christele: So definitely, like, I think it was an example of Beirut, because I know Beirut, but this can work anywhere else. And the wake up call is for everyone out there. And for everyone, not just living in cities or anything. It's just for everyone to know that it's time to make a change. And it's time to take actions, and it's time to acknowledge the power that you hold.

Alexandra: Yes, yes! Absolutely. I think that's really, you know, what we want to do with these conversations—create calls-to-action for more than just urban planners and architects—I like the idea that everyone who lives in a city can be an urbanist, we just need to activate that power, as you said.

A large part of the creative and academic community considers that the post-civil war reconstruction of the city center carried out in the 90s by real estate tycoons, has completely eradicated the previously existing urban and social fabric of the center.

In your article, you wrote about some of Beirut’s lessons from the past in terms of urban governance and the challenges they face with a lot of institutional dysfunction. You said, “A large part of the creative and academic community considers that the post-civil war reconstruction of the city center carried out in the 90s by real estate tycoons, has completely eradicated the previously existing urban and social fabric of the center”

It seems like this is a moment to redirect that and take a more people-centered, participatory approach to the city's development. How do you envision a corrective path, and what steps can the Lebanese people take toward a more stable future?

Christele: Okay, to tell you a bit more about what was happening in Beirut. So since day one, after the blast, the civil society has mobilized all of the efforts hoping to lead like proper reconstruction attempts. And because I also wanted to avoid the repetition of past mistakes, similar to what happened to the city center after the war, when we had top down imposed rebuilding schemes, and a lot of expropriation privates, is privatization and complete destruction of an existing urban and social fabric.

NGOs and organizations are actually leading these community efforts to avoid, again, a change in demographic, a demographic change, displacement of people, and of course, something that was happening before, and that was starting to happen, which is property speculation.

So these organizations are the ones actually who are fighting, everyday, to keep the original dynamics of neighborhoods and to keep individuals in their houses. And they were the one, and they are still the ones working towards rebuilding heritage buildings, and also purpose preserving the urban fabric.

We knew that in order to generate the radical change, we needed to be in the driving seat.

So in fact, these people, us, I would say, we have become a substitute for absent and corrupt corporate, governmental institutions. We knew that in order to generate the radical change, we needed to be in the driving seat.

This approach, like, was completely born out of frustration of needs, and it was very organic at first and it was individually formed. And after three months, these groups were capable of coming together and actually having a tremendous impact. While governmental entities, after three months, have only shown a great deal of negligence, lack of motivation and action. So the problem is, but the problem is when it comes to cities and planning, these people driven entities have limitations. And a lot depends on institutional decisions to lead huge scale initiatives. So we're still stuck at this point.

Alexandra: Its a moment for bottom-up initiatives to step up. How are the residents of Beirut responding as a community? What do they have the power and the ability to do, given the current situation?

Christele: So yeah, I would say it wasn't just about the residents of Beirut. It was the whole country that was mobilized. It was heartwarming, seeing everyone on the streets together, helping each other. Coming from villages and other cities to lend a hand. Like, since day one, I was there, I was on the streets trying to figure out how I can help. And a lot of people were also like me, trying to literally lend a hand to anyone in any way possible.

This tragedy somehow brought back a whole nation together. And for a minute, they all forgot their differences, and they focused on similarities.

I actually worked with a lot of people who didn't know how to help, but just wanted to do something. A lot of people used to come up to me and say, okay, we want to help but we don’t know what to do. Tell us where to go, who to help, what to do, etc. So it's this tragedy somehow brought back like a whole nation together, and for a minute, they all forgot their differences, and they focused on similarities.

So August was a tragic month, but also August, and I would say also, like September. I'm saying August, because people were on site, on the streets in August. August brought back also a new hope for the future. You could see this community coming together, and in a way they had these same ideas, and they knew that together, they could make anything better.

Alexandra: That's beautiful to hear—at the end of the day, the structures are burnt down, but there are still people.

Christele: Cities are the people.

Alexandra: Yeah, yeah. We embody the city. And it is only as good as its people.

Christele: Yeah, that's what I wanted to say. Thank you, Alex.

Alexandra: Ah ha sorry I didn’t mean to steal your words. Is there something, particularly urban designers, architects, and investors from abroad can do to help?

Christele: You know, that first, I actually think maybe it's time to look inside, rather than always look on the outside for help. Like, especially for Beirut, and especially for Lebanon, because we're so accustomed to ask [for] help from the outside or be influenced by the outside, by the west.

No one knows the city better than the people living in it-maybe this tragedy is actually teaching us to go back to what matters and to contextual solutions.

No one knows the city better than the people living in it, the artists, the architects, the craftsmen, etc. Maybe this tragedy is actually teaching us to go back to what matters and to contextual solutions. And I think it's time to reevaluate everything, totally everything from planning to construction laws, to reconstruction approaches.

And of course, it's time for change on a governmental level, because at the end of the day, cities also reflect systems and cities are the product of these systems. So in my opinion, reconstruction efforts should be driven by local perception and local vision and local craftsmanship with local materials, in order to truly reflect the people of Beirut and to reflect everything they face, and they are still going through every day.

Alexandra: Absolutely. I like what you're saying with that. I agree. The investment in local-based reconstruction could help in many ways, to restore the economy as well as some of the city's soul. I think many communities could benefit a lot from that same kind of mentality, so thank you for sharing that.

Christele: I don't know why I found it as I just want to say something more. I don't know why I see it as it's kind of like time to go back to two sources to essentials to context, you know, to the community, to the territory, etc. Like, I feel like it's the opposite of actually going global but maybe, like, be more focused on inside shoes, if that makes sense.

The destruction of the capital is not limited to physical losses, but the two explosions struck to the core, shaking the Beirut ideology, and shattering everything the city stood for.

Alexandra: It’s a theme I keep seeing or hearing about in a lot of communities. People moving around less and therefore are getting more acquainted with their surroundings, getting to know their neighbors, helping each other out. My local coffee shop was making masks for everyone. In this age of globalization, I'm happy to see that value find its place-it's so important.

Christele: And major also.

Alexandra: Yeah, absolutely. And I think this is how cities can retain identities in a lot of ways. You wrote something quite powerful in the ArchDaily piece, about the collective Lebanese memory and resiliency. It really helped me feel what you, and the Lebaneese people, were feeling, so I’d like to read it.

You said: “Getting tired from romanticizing the notion of resilience, the question tormenting the Lebanese revolve around an unknown and unimaginable future. How much can a population endure, before reaching its breaking point? The destruction of the capital is not limited to physical losses, but the two explosions struck to the core, shaking the Beirut ideology, and shattering everything the city stood for. A beacon of hope, the city has always been the personification of optimism and inspiration for all its inhabitants and for all the Lebanese diaspora, longing to return. However, Beirut today is not the Beirut of yesterday, and the collective memory of its people is in serious peril”

Christele: Well, I wasn't very hopeful, now that I hear it again. So I wrote that article, just a month after the tragedy, like for a month, I couldn't write anything, and just after it, and just after this month, I wrote the first article that went out on ArchDaily. To me the idea of resilience has become so outdated and unwanted. Like, we didn't want to be resilient anymore, we didn't want to adjust anymore. Because it was part of our pattern. It was part of the Lebanese pattern in a way, but we just want but just for this time, people were like, refusing this idea. And the future seems that it's um, really unimaginable.

Beirut was losing its past at the moment, its present, and future for a second. And we were losing Beirut, which was actually unthinkable for us because losing Beirut meant losing ourselves.

It felt like all of our memories were being destroyed, because technically, the places that recreated these memories and were gone. So these spaces that tied this community together, are shattered. And this new image that doesn't feel like us where it just was just being shown in a way.

So I always repeat something that I read once and say that to destroy cities to eliminate its past, present and hope for the future. Beirut was losing its past at the moment, its present, and future for a second. And we were losing Beirut, which was actually unthinkable for us because losing Beirut meant losing ourselves. I also think that we need the city more than the city needs us, in all cases, not just in Beirut. And because as I said before, Beirut was the personification of hope, especially for the ones that had to leave and look for a better future, but always had to return.

We need the city more than the city needs us.

Today, I would say that I'm more optimistic. And just because signs of promise have emerged here and there and I've witnessed, like these driven initiatives by the people for the city. And I don't want to say this friendless hope that we have, but I also want to say it is really established by the people and for the people. We know humans adjust and move on, but I just hope that they don't forget. That they just take a step forward, keeping the same ideas or keeping these events in mind to know how to act in the future. So these people, Beiruty people, are actually restoring what is left of our faith in a better future.

Alexandra: Restoring faith in a better future; that's crucial at this point—and I agree with you about how sometimes "resiliency" can get over romanticised, when in this case it really just means survival. There isn't space for grief and reflection when the nation is at such a crux, and it sort of sustains that collective trauma. So, what do you think the reconstruction of Beirut's cultural center, heritage buildings, and more contemporary structures will look like

Christele: Well, you know that it's true that around the world, we know how to restore traditional buildings, there are rules for that, etc. Okay, this is set, but actually how to rebuild relatively new constructions, like that's something that we never tackled before. Especially that some of these damaged contemporary architecture is like, three and five years old-—very, very recent. So I think this is a very new topic, and I actually had the chance to discuss, to discuss it with several architects that had their buildings damaged, and some of their buildings were directly facing the port, and they actually absorbed all the first shockwaves. Actually, I will be featuring their views and articles about 21st century reconstruction processes.

One thing for sure is that they all agree that you cannot, or should not, rebuild a structure as it was before the incident. Because that way, you will be eliminating old scars or marks of this tragedy. I mean, like this new reality should be in a way interpreted and integrated into our structures, we cannot just forget it. And we cannot just erase it.

I think that our buildings are like us, they go through time, experiences and occurrences and just like us, they should be the result of everything they went through.

I think that our buildings are like us, they go through time, experiences and occurrences and just like us, they should be the result of everything they went through. So of course, this is a very conceptual approach, but, when it comes to like onsite action, the decision is for developers and tenants who live in these buildings. And of course, what is not helping is the lack of funding and the economic crisis. So, I don't know how much these ideas are going to be concrete, are going to be interpreted or are going to be real.

But to my surprise, I have just learned that one of the major high-rises facing the port, the one by, that was the most affected, and where a lot of people lost their lives will not be restored exactly the way it was. So, the architect told me that people were actually keen on having a new approach. And so they work together, the people of the building with the developer with the original architect, they wanted to have a different approach, they wanted to find a new way to rehabilitate their buildings.

So utilizing materials from the blast, upcycled and recycled. Of course, I also wanted to think about local stuff, like local craftsmanship, local know-how, local materials, etc. And to me, I find this super motivating and enlightening that these people are actually thinking this way. And this is not just an architectural approach, and that this might lead into something super interesting.

Alexandra: Absolutely. It will be interesting to watch—what comes of Beirut. I don't want to say it's a blank canvas, but it definitely has some, some new pieces to work with to truly reinvent itself.

Christele: I agree, also, and I think it's just time to rethink everything. So everything that happens has to be taken as an opportunity to evaluate and to draw conclusions and move forward, like forward with very short steps, I would say.

Alexandra: Yeah, absolutely. And Christele, we touched on this briefly, that this incident being a real tipping point for Lebanon, as the country was already dealing with a great deal of other stressors, including a pandemic, and an economic crisis. Can you set the scene a bit more of what the city looked like pre-explosion?

Christele: Well, of course. So actually, the whole country was going through a lot of things before the pandemic. So we started having a crisis, I think, since October last year. So there was this economic crisis. People were revolting. They were taking the streets, taking their demands to the streets. We were protesting all the time. Like similar stuff that is happening in Chile and China, etc. So, already the country was not stable, I would say.

On top of this, we had an economic crisis, the currency has lost its value. Around February or March, we started having lockdowns from COVID-19. A lot of people were like, not working, etc. So I think after that also, like we had the blast that happened in August. So if I actually retraced the whole year or so, we had the economic crisis, we had the protests, so we had COVID, and then to top it all, we had the blast.

Reconstruction efforts should be driven by local perception and local vision and local craftsmanship with local materials, in order to truly reflect the people of Beirut and to reflect everything they face, and they are still going through every day.

I would say I don't know if the Lebanese people can still take anything. And I don't know how much they can still endure. I don't know how much we can still endure. But it has been a very, very tough year. And it's also impressive to see people still adjusting and still trying to figure out things. A lot of people, to be honest, have left the country for better opportunities, but I feel like the whole word actually is not a good place to be right now.

Alexandra: It's tough. Christele, thank you for sharing your time and your valuable insights with us. It was great to have you again on the podcast.

Christele: Thank you, Alex. It's always my pleasure.

That was the managing editor of ArchDaily, and Beirut native, Christele Harrouk.

Alexandra: It was really special to have [Christele] back to address such a critical topic—a city at a breaking point. While there certainly are glimmers of hope, the threat that Beirut faces is still tremendous and shouldn’t be overlooked.

Following our recording, Christele has since published another piece on the city, titled The Contemporary Approach to Rebuilding Cities Post-Disaster: The Case of Beirut. Interviews featuring architects "who’ve recently completed newer, contemporary structures which are now facing reconstruction dilemmas, and raising existential questions such as: How should reconstruction efforts of “new” damaged buildings look like? Should architects rebuild them as they were before the blast, erasing everything that has happened or should they leave scars to portray the new reality?"

How should reconstruction efforts of “new” damaged buildings look like? Should architects rebuild them as they were before the blast, erasing everything that has happened or should they leave scars to portray the new reality?

One of the architects interviewed, Paul Kaloustian quotes a philosopher, Alain Badiou, and his proposal to “take some distance, think of new possibilities, of a new world, and not just get busy with reconstruction without taking the time to invent something new.” It’s a poetic exposé of visions for Beirut’s future made possible by taking a moment to truly recalibrate with purpose.

For the second part of our podcast, we’ve asked another Beirut native, Salim Rouhana to join us. Salim is a Senior Urban Governance and Resilience Task Team Leader at the World Bank Group.

With a background in architecture and political science, he considers himself an activist for better urban living, focusing primarily on areas related to decentralization, city competitiveness, urban resilience, disaster risk management and urban and local governance, all throughout the Middle East. Salim was involved in preparing the Beirut Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment, along with the Reform, Recovery & Reconstruction Framework on behalf of the World Bank following the August 2020 blast.

Alexandra: Hi, Salim, thanks so much for joining us on Design and the City.

Salim Rouhana, World Bank Group: So first of all, thank you, Alexandra, for having me. And I'm very happy to be on your platform. I think this is really a great opportunity for me to share, particularly on this you Beirut explosion experience and what's happening afterwards.

Alexandra: You are most welcome. We’re happy to have you. So I guess let’s jump right to it-were you in the city the day of the blast? What was your experience like?

Salim: So just to, to maybe give you a little bit of a background on what happened, and I'm pretty sure you covered that pretty well. And almost all people do know what happened in Beirut this summer. I was there in Beirut, I was sitting in a cafe working and really the explosion destroyed almost the entire cafe where I was sitting. And I went out and I was looking around, and seeing people screaming and walking. And, and really, there is no there is no way to explain, if you will, the amplitude of what happened. You can see that in videos and pictures, but it's just a really traumatising experience for me, and for many people who were in Beirut.

And I have to say, for all people who love that city, which is a very particular city; very energetic city, very creative city, and a city that always managed to bring the best out of people. Since the explosion, despite the lack of government intervention and capacity and willingness even, to intervene, to react and to respond to this crisis, I have to say that civil society and people of Beirut and Lebanon managed to really respond in a magnificent way.

The same day, the second day, I was there on the streets, and I saw thousands of young women and men going down to the streets, supported by the Lebanese Red Cross by existing established NGOs. And really just to help people who are on the streets, to pick up their wounds, their immediate wounds, and respond really to the immediate shock that this explosion had.

I have to say that civil society and people of Beirut and Lebanon managed to really respond in a magnificent way.

Very, very rapidly after that, we saw the creation of a lot of civil society organisations and movements that are specialising in recovery and reconstruction and rehabilitating, what I call houses and souls. So a lot of focusing on, you know, vulnerable communities and vulnerable households to be able to help them rebuild their windows, their shattered houses, but also trying to help them with medical support, with post-traumatic support, psychological support.

And really, we saw a lot of a lot of innovative initiatives happening on the ground to be able to really bring that dynamic and to have to leverage each other's skill and an interest to really help the most vulnerable. And in that area that is affected, which is Medawar, Gemmayzeh, Achrafieh, Karantina—there are tons of vulnerable households, be it elderly, be it poor, Lebanese and refugees, among others, women-lead households, who really have been hit the most out of that, from that explosion, and that the impact of that crisis.

Alexandra: I keep hearing that—how people have come together. Were you able to get involved?

Salim: So, I have to say that, you know, in addition to that kind of very amazing drive and energy of civil society, I had the opportunity or the occasion to be in Beirut at that point in time and I mobilised as well immediately, with the World Bank, which I work for. That was also a great opportunity for me to really do something and immediately. So that next day, we put together a large team to prepare, with the European Union, with United Nations, something that we call the Rapid Disaster Needs Assessment, Damage and Needs Assessment, so the what we call the RDNA, the Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment, that really brought together a lot of stakeholders that are doing assessments that are interested in assessing the damage.

Because the first thing to do, in addition of course, the humanitarian support that needed response to be able to really quantify and mobilise resources and understand the level of damage of this explosion—on people, on households, on individuals, on businesses, on small and medium and micro enterprises—which the area is extremely rich [in], to really understand what are the damages, what are the needs and how to recover from from that impact.

I felt that this purpose and my existence, at that point in time in Beirut.

And I had really the opportunity to mobilise immediately, I felt that this purpose and my existence, at that point in time in Beirut, that at least a lot of my personal trauma, because I was mobilised, I tried as much as possible with my colleagues, my friends, everyone around to work with civil society with other stakeholders. And then the government as well, to be able to really bring this assessment together and also have it as an instrument to allow everyone around to understand the scale of the impact of that explosion.

So really, immediately after that, as explained, everyone mobilised, you know, there is a lot of excessive and I think I have to give a lot of credit to the Lebanese Red Cross also mobilised an exceptional way, not only humanitarian aid, not only on the disaster response, but also doing a lot of the assessments that are extremely important and extremely crucial to mobilise donor community and others.

I saw a city rising from ashes.

A lot of Lebanese living abroad and in Lebanon, also mobilised, a lot of fundraising happened, tens of millions of dollars were immediately mobilised by private individuals, to be able to respond to the most vulnerable households. All of that dynamic, I think, and I believe, helped the city cope better with the shock that it was hit by.

And also, of course, it also helped a lot of young people, young women and men, find purpose, particularly with anger or frustration. They really managed to find the kind of purpose and to be able to deliver and to work on the ground directly with a lot of those that organised civil society groups and movements and NGOs.

To be able to allow the local economy, particularly in those affected areas that were completely destroyed, to be able to rise again, to bring value, and to really put Beirut where it belongs.

I left Beirut in October, so I live in Tunis, I left Beirut in October to come back in December. I saw a city rising from ashes. It's not only metaphorical, it's very visual—bars, pubs, cafes, businesses are reopening progressively at a speed that you know, you can't but admire. But there is much more to do. And I think that is something extremely important with private initiative, with private goodwill—it's not enough.

There's a lot to be done to be able to recover effectively from the shock, to be able to build back better, to restore faith in institutions and government, to be able to allow local economy, particularly in those affected areas that were completely destroyed, to be able to rise again, to bring value and to really put Beirut where it belongs—in a competitive place economically, culturally, socially among among others.

Alexandra: What would you say were the biggest takeaways? What was learned?

Salim: First of all, what I learned is that this is not only anecdotal, but it really takes a village. It's not [just] one's business to rebuild to recover from this disaster. Everyone has something to do in this recovery because this explosion didn't only affect Beirut, it didn't only affect people's lives and you know, more than 200 people lost their lives. Thousands among them, my friends and my relatives, were wounded and had to be hospitalised. So [it] didn't only affect those, it didn't only affect those who lost their businesses, their jobs, their houses, or you know, or had damages and all of those; this explosion affected the entire country.

What I learned is that this is not only anecdotal, but it really takes a village.

This collusion is first of all, a testimony of failure of governance. Neglect. Corruption. But, it's also a testimony, and it led to a complete loss of faith, of politics and governance or, and it will also lead, of course, to another compound impact to many of the impacts that we've been witnessing, and many of the crisis that we've been witnessing in Lebanon—economic financial, security, fragility, refugee crisis, the financial again, non-banking sector collapse, among others. So this shock really was a and then the COVID crisis, of course, not to mention the revolts on the streets—this explosion came to give it a final head.

But I have to say, this is also an opportunity to decide on what path Lebanese citizens, organised groups and government, where do they want to go? What scenario do they want to take to recover? Do they want to go for the collapse? That's a scenario. Because, that kind of explosion with the COVID crisis we're witnessing and the political crisis, usually could lead easily to a full collapse of the economy, which we’re witnessing parts of it, but not only full collapse of the economy would also have the social contract and the social stability that we know.

Can we use this crisis, this tragedy as an opportunity to rise better? To recover sustainably, inclusively, efficiently? Is there a way to recover better?

The second scenario is to try to come out with the most mediocre of situations trying to say, well, let's try to recover with least damage and least opportunity possible—go back to the status quo. That's what I call the missed opportunity. So the first one is a disaster. This is a missed opportunity.

And the third scenario is to say, and that's part of RDNA and our RRF, and how we build that kind of recovery framework, is to say, “well, can we use this crisis, this tragedy as an opportunity to rise better? To recover sustainably, inclusively, efficiently. Is there a way to recover better?” And that's where you need everyone—you need a village to do that. You need, again, individuals, civil society, government, politicians, groups of interests, syndicates, universities, you need everyone to be mobilised to be able to move this country forward and to use this opportunity to recover better.

And that's where you need everyone—you need a village to move this country forward and to use this opportunity to recover better.

And then the three RF and RDNA present a little bit the framework in which you could use and you could leverage the financing, the reconstruction, and recovery effort to be able to build a better country broadly. So how to move forward with reforms, how to move forward with transparency, accountability, how to build sustainably—a lot of things I think are there, and those frameworks, they're not the solution, but they give you an idea of how you can really recover back?

Alexandra: So we know the Lebanese economy was already crumbling prior to the explosion—and we already touched on this a bit with Christele—but perhaps you can add more insight. Can you speak on the state of the country leading up to the explosion and what other factors played a role?

Salim: So, prior to the explosion, the country was going through multiple shocks. The Arab Spring had its ripple effects on the country-the destabilising of Damascus, the destabilisation in Syria, the refugee flows are more than around a third of the Lebanese residents in Lebanon today. That's what you know, there's a lot of numbers that say between 20 and 30% are refugees. So those are extreme pressures on your economy, and also an opportunity, I have to say. Particularly the Lebanese managed to, and they have to say that, you know, the stability and the, and the peace that was there I think is a testimony of the close ties and relationships between the two people, but also of the hospitality.

And on the other hand, you had, of course, a political crisis that is enduring. I don't know, those who know, and I'm pretty sure a lot of people know what's happening in Lebanon, but we're inheriting a lot of political issues for decades. Major divergences and political opinions, perspectives, and visions, that are hardly reconcilable. lack of trust in government—full lack of trust in government—due to real and perceived corruption, due to weak governance structures and models. Really, very weak states, I think we're also weakening that further, because the political tensions and divergences state is just weakening further and further.

Also, Lebanon is not away from the economic shocks that are hitting the world, but particularly Lebanon, because of, again, the the weak governance, a lot of mistrust, a lot of mismanagement of, of public resources, the country is facing also one of its worst economic crisis, in particularly with the collapse of the financial system in Lebanon.

So all of those, in addition to the COVID crisis, which is just, you know, I think the last nail in the coffin put it that way, our compound of risks that no country is able to manage, particularly when you have a humongously divided political elite and a very weak governance and a full lack of trust and the political system, political and governance system. So that is the situation before the explosion, so the explosion just gives it a hit, that you know how to flip it around and build better, or you're just going to go into full collapse.

Alexandra: Lebanon has really been through so much. So, how do you rebuild, where do you start? How do you set your priorities?

Salim: First of all, there is value in vision. Today, the country, as I mentioned, lacks complete consensus on what its future should look like. And that by future, I mean, its economic future, its social future, and its political future. There is really a complete vacuum of vision today on where this country can go. Same thing could be said about the recovery and reconstruction that is a complete lack of vision of what recovering from this current shock should look like.

So really, compensating people for losses of assets, loss, supporting those who lost and were affected by this crisis, who lost, particularly those who lost their loved ones. Really being in their support, supporting the most vulnerable. And then on the other hand, because Beirut is particularly the area that was affected was by sum kind of somehow the heart of Beirut's creative industries, which are very well known in the region and globally. t's also trying to support those to become even better than they used to be.

So recreating creative industry value chains, linking producers to designers to, to markets, really use this opportunity to say, well, this used to be the heart of Lebanon's creative industries of Lebanon's even artisanal industries, of Lebanon's small and medium enterprises. How can we do that better? How can we rebuild that better? How can we reshape that better? And I think there's a great opportunity there today, the Beirut brand on any type of an item is really appreciated, globally. How can you support those? And there's a lot of programmes that you can do.

Government led civil society to really recreate jobs because people are then once you fix their homes and fix their neighbourhoods, and you build better, what they're interested in and they need on the longer term is those jobs. They need to feel involved economically. And I think that's something you need to think through while thinking how to rebuild that infrastructure, the services, the quality of life, the house, the houses. Also how to rebuild the economy, how to rebuild those small and medium enterprises that were extremely affected and damaged in this explosion.

Alexandra: Something I’ve seen a lot of — and I’d love to hear your take on it — is how architects and other designers should go about rehabilitating buildings, with discussions on both modern buildings where the architect is still practicing versus heritage buildings.

Salim: So I have less of a concern for modern architectural buildings because you know, the architects are still there, a lot of the enterprises that build them are still there. So there will be ways of rehabilitating them, and stabilising them, and making sure that people can go back to their homes safely and rapidly.

My real concern is on the heritage, and relatively the post-heritage buildings, which are in a catastrophic situation after the blast, and also the that do house a lot of you know, middle, lower-middle and poorer communities in Beirut. And I think there's a lot to be done there. And there's a lot of creative ways to rebuild while keeping those vulnerable households in their homes. And I think that's extremely important. Because the wealth of Beirut is a mix of two things. It's built heritage and its people. You can't lose one of both, you cannot afford to lose any of those two.

So as we mentioned earlier, the people we want to preserve them, we want to keep them, we want to make sure that they are there, they arere strengthened. And also the built heritage needs to be restored and be the kind of recipient for the creative industries that we spoke about but also for the communities-vulnerable and non-vulnerable. There are a million ways to do that, through specific interventions, funds to restore heritage. Hopefully the donors such as the World Bank and you know, the international community will also mobilise the resources to rebuild that tangible heritage or beautiful architecture that the city holds.

Alexandra: Beyond the physical damage, what do you feel is the “unseen” damage to the city and its economy? How are people and city makers facilitating the long term emotional recovery?

Salim: So that the unseen damage as you say, it is particularly the psychological damage? So the people from Beirut and from Lebanon are going through, maybe one of their worst traumas, and a lot of my friends that I speak to, and my family, they all tell me that this is, even as a trauma, might be even worse than the civil war that we've been through for 15 years.

I believe, you can restore anything, except for the loss of people, those are generations lost.

It was so sudden, so shocking. people, young people are losing hope. So we're having maybe today, one of the worst brain drains in our history. Those are the unseen impacts--people's well being, people's psychological well being. And also the entire skills and resources and young women and men just leaving the country in waves, because they don't see any more future for them there.

I believe, you can restore anything, except for the loss of people, those are generations lost. And when you lose generations, it takes you manage generations to build that back. And I think that's really, there is a lot to be done, to try to reduce that flow of talent, emigration of talent. That's just going not because they want to go because they're pushed to go, you know. I'm someone who left the country, but I had a great opportunity, I was very excited and eager to travel and discover the world. But it's sad to see people who want to stay being pushed, continuously pushed. And those are the last generations of this country of Lebanon, that will never be recouped, again, that will never be found again.

Alexandra: Where is the trust, or hope, for Beirut's future coming from?

Salim: So I feel that, you know, I really, personally, I feel that there is an important role for the government to play in the next five to 10 years. We can't win the country without the government without an existing and new political elite, a transparent and accountable government, and inclusive, sustainable.

I do believe that there is a way to rebuild better. And that starts from government, working very closely with civil society, with academia, with individuals—really working very, very closely to build a collective vision on how we want our city, first, and our country to look like in the next 5, 10, 20 years, and then really work together in that direction.

So the way forward, and the only way forward is to collaborate.

And work particularly transparently and inclusively. Because, you know, that's something we don't know how to do near Lebanon or in other countries in the Arab world. We are very weak when it comes to really building systems of comfortability and inclusion, and but this is something we can do. They're easy, the techniques are easy, the tools are easy. So the way forward, and the only way forward is to collaborate. Put the resources needed, and we are talking about hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars—put those resources to build back better. Because, economically, in the future, we would recoup that.

So we need to recover. We need to build, we need to do it the right way. There is no ‘you can do this twice’.

So we need to recover. We need to build, we need to do it the right way. There is no ‘you can do this twice’. This is one of the lessons we learned from the post-war reconstruction in Lebanon, is that you cannot reconstruct twice, you do it once. So you have to do it well. So Beirut deserves to be built back in a very, very inclusive manner, really to have the voice of people living there and involved there heard while designing the city of the future. And then think through the reconstruction architecturally, aesthetically, economically, socially--really think creatively on how you're able to build that city to become a beacon of hope, not only in Lebanon, but also in the Middle East. As it always has been.

Alexandra: Absolutely. Urbanism and good governance are just so deeply linked. What lessons can we learn from good examples of regrowth and recovery after natural and manmade disasters in other parts of the world—ones that Beirut can adapt to?

Salim: So one lesson, I think, that we take from all of those examples is one that I've already mentioned, which is you only have the chance to rebuild once. So the kind of trial and error doesn't work with the construction. You really have one chance to do it, to do it well. And because you have one chance to do it, I think you have to do it in a very inclusive manner. Because, you might think that you know what people want, but you really don't know anything.

You cannot reconstruct twice, you do it once. So you have to do it well.

So really, I encourage anyone convening in the public space in Lebanon, is to really be the most inclusive possible, and the tools and instruments—be it online, be it physical, virtual, [there are so many] numerous and so [many] creative ways of engaging with kids, with youth, with women, with men, with elderly, with different marginalised groups as refugees and more gender-based, vulnerable groups. There are a million ways of building this collective vision and really working together into achieving it.

Because, you might think that you know what people want, but you really don't know anything.

So you have one chance, and you have the chance to do it very inclusively. I think that is what I would take from a lot of the experiences we had in Lebanon. We have rebuilt Beirut multiple times, and have rebuilt our country multiple times, particularly during and after the Civil War. You mentioned the Haiti—very different case, but also quite dramatic, traumatic, also disaster. The second world war you know, cities across the world that faced different types of damages and disasters, really, you only have one chance to do it well.

Alexandra: So, Beirut in 10 years—what does that look like for you?

Salim: That's, I think that's the most that's the toughest question, but I'm gonna, you know, like, I don't know how much you know about Lebanese culture, but we love reading and coffee cups, you know, fortune telling, we love those things. A lot of old traditions into fortune telling. So, if I'm, if I'm reading a positive cup right now, and I'm seeing Beirut in 10 years, I would say that I would see a city filled with light.

I would say that I would see a city filled with light. The city where people have an amazing access to public services. A city that is clean, green with clean air. A city that is inclusive for all, created for all. A city of innovation, which it continues to be but it can be much more than that. A city that inspires. A city that is the heart of freedom of expression.

The city where people have an amazing access to public services. A city that is clean, green with clean air, which is nothing of what it is today. A city that is inclusive for all, created for all young people—men, women, vulnerable communities, refugees, migrants—and attractive to all of those groups, so that it's really a city that is just a hub, a city of innovation, which it continues to be but it can be much more than that. A city that inspires, a city that is the heart of freedom of expression, which is one of the rare spots today in the Arab world.

And it continues to be, again, a city of light. Today, it is not a city of light. So I hope that in 10 years, this has messaged to a lot of people to go visit Lebanon, a lot of Lebanese who are aiming to leave, to rethink, because I believe that with the energy I saw when I see and I continue to see, there is hope for the city to become all of what I've mentioned above. That's my vision. That's my dream.

Alexandra: That's beautiful. I think that's a good dream to have. Salim, thank you so much for sharing. Is there anything else you feel we didn’t speak on, or that you’d like to add?

Salim: Honestly, you know, I think that, first of all, I want to thank you a lot for this opportunity. I really am. I'm so passionate about what they wrote about Lebanon, about architecture, what economic recovery and social recovery. So I'm really very grateful for this opportunity today. But I have to say that there is hope, there is an opportunity.

Those inhabitants have proven more and more not to be particularly resilient, but to be creative, to be forward-looking to find solutions to climb out of there.

And I am one of the few today who see light at the end of the tunnel, not because the political, economic, or geopolitical situation allows it, it's just because, you know, Beirut is all about its citizens, its inhabitants. And those inhabitants have proven more and more not to be particularly resilient, but to be creative, to be forward-looking to find solutions to climb out of there. The challenges that they've confronted, and that really gives us hope for the city.

For its content, and for its economy. So I'm really very hopeful that in a few years, time and few months, I have to say, in a few years, we'll start seeing recovery of the current of the Aveda that we know of loving and that we know, despite the time that it will require to recover fully. Thank you.

Alexandra: Thank you Salim, it was our pleasure.

That was Salim Rouhana, Senior Urban Governance and Resilience Task Team Leader for the World Bank Group.

I think it’s safe to assume if you are listening to this, you care about cities, and their communities, etc, and probably feel a deep empathy for what has happened to Beirut. If there’s one thing we’ve taken away from both Salim and Christele’s powerful testimonies, it’s this bright, bold hope that seems to be rising from the dust, by way of the Lebanese people—a hope that feels contagious. And, I’m grateful that reSITE is able to use our platform to be a steward of these stories. It is truly as Christele said, that cities are really just people.

A special thank you to our guests for their collaboration as well as both Elizabeth Mills and Elizabeth Novacek for their contributions in creating this episode.

Design and the City was recorded at the WeWork offices in Prague, with the support of the Czech Ministery of Culture and Nano Energies. This podcast is produced by Alexandra Siebenthal, with support from Martin Barry, Radka Ondrackova, Elizabeth Mills and Elizabeth Novacek and edited by LittleBig Studio.