The Architecture of Healing with Michael Green + Natalie Telewiak

Michael Green and Natalie Telewiak love wood. These Vancouver-based architects champion the idea that Earth can, and should, grow our buildings--or grow the materials we use to build them on this episode of Design and the City. Photo courtesy of Ema Peter

“I think us moving to the connection of where materials come from, understanding what it means to plant something and to wait, is really the cultural shift that happens to help us embrace the idea that cutting down a tree can be bad, but it can be wonderful as a source of solving, you know, our real challenges of today and tomorrow.”

Listen to Michael Green + Natalie Telewiak on Design and the City:

They are the principals of Michael Green Architecture, or MGA, and have made it their mission to tackle world housing and climate change by harnessing the power of timber, which they call “the most technologically advanced material we can build with,” to sequester carbon, to accelerate construction and reduce local disruption, and to create spaces that foster a more holistic well-being in our built environments.

Founder Michael Green has been recognized for his advocacy of wood use in architecture, which has taken the form of three widely viewed TED Talks, the founding of education and research-focused nonprofits, Timber Online Education and Design Build Research, as well as an open-source feasibility study titled, “The Case for Tall Wood Buildings,” which outlines his mass timber construction model.

Natalie Telewiak, a longtime colleague and collaborator at MGA, brings her unique perspective with a background in both architecture and engineering to the table. In 2018, Natalie became a Principal alongside Michael.

Watch: Why we should build wooden skyscrappers

The two lead an ambitious team responsible for some of the largest modern timber buildings in the world, including The Wood Innovation Design Centre, a mixed-use, research and commercial gathering place in Prince George, British Columbia and T3, a seven-story, LEED Gold Certified mass timber office building in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

In this episode, Michael and Natalie dive deep into the ethos behind their design and material choices in some of their standout projects, like the Ronald McDonald House of British Columbia and Yukon, with reSITE founder, Martin Barry. They weigh the advantages and limitations of mass timber construction and dissect the complex nuances faced when striving for true sustainability.

One could argue, what is sustainability without community? Without affordability? Without connection? As pillars of MGA’s practice, it is the combination of these factors that render their work both remarkable and mindful. Their projects are rooted in the local ecosystem and designed for inhabitants to build connections to nature and to each other--an architecture of healing on many fronts.

Martin Barry, reSITE: Okay, good evening, everyone. And welcome, Michael Green, and Natalie Telewiak from Michael Green Architecture. We're so happy to have you guys, from one of my favorite places, Vancouver, Canada. Welcome to the show.

Michael Green, MGA: Thanks for having us.

Natalie Telewiak, MGA:Thanks. It's great to be here.

Martin: So, guys, I haven't been to Vancouver in a long time. So let's just start really briefly; tell me how it's going there. What are you up to? What's new in the city? And what's inspiring lately?

Michael: Yeah, well, things are obviously strange with COVID, but Vancouver is doing well. And, you know, the city's thriving. We're an interesting city because we've been in growth for a couple of decades now, without really much of a dip with the economy, or even COVID. So, you know, it's thriving, there are a lot of people moving into the city. It's an incredibly beautiful city, as you mentioned, we're surrounded by the mountains and the ocean and a great fortune: a lot of wilderness, a lot of great forests, around us.

Some wonderful, big buildings are going up, but still not enough in wood. And that's something that, obviously, we're trying to change. But we are seeing some real movement there. And we have some pretty exciting projects coming up, here in Vancouver, as well as the things we're doing in the rest of the world right now.

We're so lucky to be knit within our natural environment, and how that's becoming infused within our public spaces and in our urban areas.

Natalie: Yeah, one of the exciting developments has been how sustainable transportation has really evolved to be knit throughout the cities. We've had the addition of lots of different bike lanes, knitting together public spaces, and [we're] seeing, particularly through the summer, how that's even being accelerated through how we've used our exterior space during COVID, and during the pandemic. So it's one of the things like Michael said, we're so lucky to be knit within our natural environment, and how that's kind of becoming infused within our public spaces and in our urban areas. It's just really exciting and provoking a bunch of different design-oriented conversations.

Martin: That's great. And have your like, I guess--you know, I'm always inspired whenever I visit Vancouver, and every time I go, I think, why don't I live here? You're close to the ocean. You've got the bay in the city. It's like a one-hour drive to some of the most beautiful parts of the Canadian Rockies. And, I guess, this has got to inspire your work; does it?

Michael: Yeah, you know, it's an interesting thing with our team, and with Natalie and I; we are all very outdoor-oriented people. So, I think, a lot of people choose to live in Vancouver because they love the outdoors. I think our firm is no different, that everybody's out on the weekends. I just came back from the Canadian Rockies this weekend, doing some climbing with my son, and people are skiing, people are on the ocean, people are running.

I think we are strong in our natural connection, [but] we still have a lot of room to grow, in our cultural connection and our social connections.

And like Nat said, the public space that we have, that connects us with the wilderness, makes us a pretty special city. But what's interesting is we also feel like we have so much more to improve on with that connection. And it's a city that's maturing and, you know, I think where we are strong in our natural connection, we still have a lot of room to grow, in our cultural connection and our social connections. So those are things that we're also really focused on as a practice.

Martin: I think that's a good way to start. And your work is known, a lot of people know you through the work you've done on timber and sustainability. And, of course, the TED Talks you've done have been really popular, and it's been super inspiring for us. But before we get there, I kinda want to step back. And I think it's a good segue, that we just mentioned, how your physical place is tied to your well-being and also tied to your practice. So I want to jump in, maybe from a philosophical level, and start with well-being and wellness. And then, I think, we'll build into the story of how sustainability and timber play into that because materiality is such a big part of how we can make people feel and connect with architecture. But I really liked some of the things you said when you talked about the Ronald McDonald House in Vancouver.

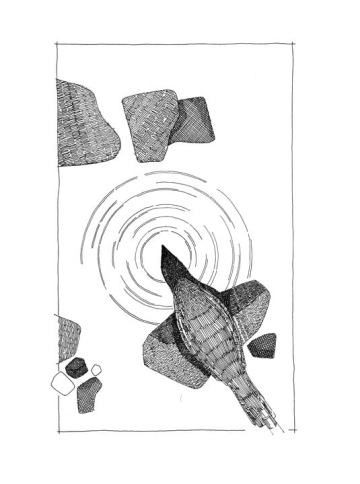

First of all, with Alpenglow and the story that you created, that I think inspired some of the design. But also about this idea of—well, you talk about concentric rings in the design—I would say it's almost like a nesting of scales and how this kind of nesting, or these rings, in architecture, can help us deal with the psychological aspects of the architecture you're creating. I thought that was really fascinating. And how did this building develop? How did you come up with the ideas of the building and these different scales and the rings? Can you talk a little bit about that?

Natalie: Absolutely, you know, one of the opportunities with that project was to really think about the experience at a personal level, and I think recognizing that many of the families that will be staying and are staying at the house, are going through a tremendously difficult time in their lives. And, so [we're] thinking about, ‘what does wellness support [look like]? And how can architecture impact that?’

So really, we thought about starting at the family, starting at the child, even, and thinking about around that family, and around that child, what would support look like on a social level? So, how can we create spaces that could really encircle that individual, to provide that support? But also recognizing that we need to provide a real diversity of spaces, and recognizing that there's space for quiet, and space for togetherness. And really, ultimately here, the concept expands to think about the province.

What does home feel like in the context of architecture?

So, people that are coming to the house are often undergoing treatment for cancer at the Children's Hospital, which is right next to the site. And so, thinking of our site, not just as that immediate property, but really the province, at a larger scale. So linking then, to the places—the forest, the environments of those different places—within the province, and thinking about what does home feel like in the context of architecture? And connecting to those, we looked at those concentric rings of support also being linked to different environmental factors.

So thinking about how we link to places like our coast coastlines, and to our treetops? and through the art and the spatial organization of those, linking to those natural environments. So as much as looking at the wellness, and calming properties of natural materials, which have been proven time and time again through different studies that we do—our stress levels are lower, our heart rates go down when we're near natural materials—also linking to those stories. So thinking about how to create that feeling of home within the kind of larger design concept.

Michael: You know, Ronald McDonald House, probably for both of us, is one of the most special projects that we've ever done, and also one of the most special projects you could ever do. It's a privilege to work and serve families, they're going through this really terrible time with a child with cancer.

It's a privilege, but it requires a deep investment in [and of] itself, and we were really privileged to get to do it.

And the project, for us, the stories that Nat's talking about were really, really important to connect through the process of the design, and then the end product, to connect people to the meaning and impact that we can have through the project. And, you know, there were literally moments in that project where the other contractors were tearing up over the impact that they were having, just by participating; we felt the same way. And I think when you have an opportunity for design to have that kind of impact, it's a privilege, but it requires a deep investment in [and of] itself, and we were really privileged to get to do it.

Martin: Can you talk a little bit about Alpenglow? I read it, and I heard part of the story that you recited, and I saw the illustrations; by the way, everyone on my team wants illustrations for their home. So, well done. But tell me a little bit about this, because it's not often that architects write stories.

Michael: Yeah, you know, I guess I want to say two things about it. So, for us as a practice, we really are very much a team environment. And there's sometimes a tendency for, I think—externally to architecture—the sense that there's a preliminary sketch that becomes the building, but of course, that's not how it works. There's all this deep thought that goes into it. About halfway through the design process, working with Natalie, and Justin Bennett who helped lead the project with Natalie, the ideas were sort of gelling to a point where the story of Alpenglow just, sort of, popped into my head. I've written, now, 13 children's books and illustrated them—most of which are not published—but they each have a kind of deep story behind them that, honestly, is pretty personal. But in this case, Alpenglow became the story, a metaphorical story, about the way that the design was evolving as it came from the team, came from us as a group.

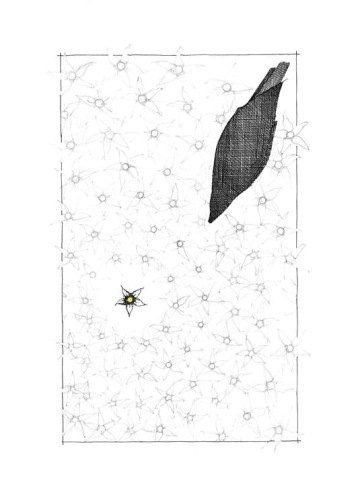

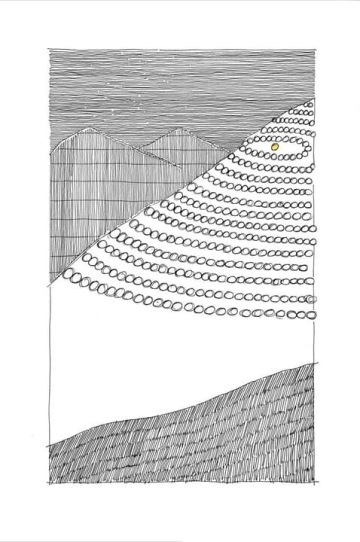

And the story is one about a bird—or a little seed that floats up into the mountains—and a bird that watches that little seed start to grow on the mountaintop, but then start to struggle in terrible winds and start to really be under a lot of distress. And the bird realizes that if she plants seeds around, in a circle, around that little flower, a new ring of flowers will grow up and start to brace her, that little challenged flower, from the winds. And over time, the bird plants ring, after ring, after ring of flowers around that little flower that we call ‘Alpenglow’. And eventually, the hillside becomes a meadow that supports and nurtures that little flower, Alpenglow, such that she thrives and survives.

For us it was the metaphor of what it means for a child to enter Ronald McDonald House, sick with cancer, and be surrounded by their family. And then that family is surrounded by other families, surrounded by a whole house.

And that story, you know, for us was the metaphor of what it means for a child to enter Ronald McDonald House, sick with cancer, and be surrounded by their family. And then that family is surrounded by other families, surrounded by a whole house, the Ronald McDonald House, surrounded by the Children's Hospital, surrounded by, really, the city, the province, and the territory, the Yukon, where the kids all come from.

So, you know, it was this idea that the design, the functional design, also had that sort of layering of stories and rings. And so sometimes those inspirations come in different places. But for me, at that moment in the process, the story of Alpenglow really kind of gelled the idea of where the design was at. But I always hesitate because, you know, I don't like that sometimes that story can overshadow the reality that this is an idea built of a team. I just composed a book that worked for what the team was doing at that time.

Martin: Yeah, that's clear [about] the design; a design, I think, that's so thoughtful can't come from one individual mind. It's clear that this is a team effort. And Natalie, I feel I can maybe cut you off. Did you have something to add to that?

Natalie: Oh, no, I think that one of the real values of the story is how it's been knit throughout the house. And there are little curious moments of the different characters, and the storyline of the flowers and the birds throughout this house, which I think adds to those layers of discovery that are so important when people are staying there for such a long time.

And one of the discussions we had quite early on was, how does this architecture, how does it speak to the feeling of home? How can it connect to that scale, while also housing 73 families? And part of that is it’s broken down into houses, certainly the courtyards and connection to safe, wonderful outside spaces. But the other [part] is this network of stories that link to that experience, over time. And I think that's been something, just talking with families who are experiencing that, that just adds to the overall sense of wellness and connection, the shared experience when they're at the house.

We don't see architecture with these sort of boundaries that we have to stay within.

Michael: Mm-hmm. One of the neat things for us, and for me personally, actually was that Alpenglow, the words of the story that I wrote are written on the front entrance when you come in. And when they started bringing volunteers into the building, they realized it was a great way to introduce what it means to be part of the house, and what it means to be part of supporting and nurturing families and children. So, you know, it became, sort of, the guide for new volunteers to start with.

I think the history of design, and the tradition of design was that we didn't see architecture with these sort of boundaries that we had to stay within. Once upon a time we designed everything, from the furniture, to the clothes, to the building structures. And there's something about a project like Ronald McDonald House, that sort of speaks to that. We were able to be part of every aspect, including literally writing the guide for volunteers that would work there. That's the best of the best for us, when we can have that level of contribution.

Martin: Yeah, I love that, and tell me a little bit, I think Natalie, you mentioned it a little bit before but the wood in this building—how does the wood structure provide the environment for healing? Is it--for those listeners out there that maybe aren't familiar with the material in architecture, how deeply can this affect the physical and mental well-being of the users or the people inside?

Natalie: Absolutely. You know, I think one of the kinds of really impactful uses of wood in this building is that it's really at the places of gatherings. When you look at the diagram of the building, we've got four houses in a quadrant, linked by two central dining rooms, and at the very heart of the building, there's one large family room. And those spaces have CLT, so cross-laminated timber, local Douglas-fir roof structures, therefore, you can see them within the dining room, within the living rooms. And they also link together play spaces outside, courtyards for sitting and gathering.

And that connection to the natural material, it really goes—it's almost something you can't even quite put your finger on. But each piece of wood is unique, each piece has a story, just like each of us, [of] where it's come from in the province, the kind of journey it's taken. And I think that part of that connection to the material is just that it has that unique story and connection to place. And then the other is just that physical warmth. I think more and more, when we see the impact of experience within wood buildings, it's really creating that connection and love of being within a space, that we really see mostly with natural materials. It's that bigger understanding of our world and how we sit within it.

It's creating that connection and love of being within a space, that we see with natural materials.

And how our spaces—some of those are natural, some of those are constructed—kind of shape that. So I think within the building, in those central spaces, connection to that warmth of material is one really strong aspect of the timber. The other is actually more hidden and quiet, and that's the structure of the main houses. So in the four quadrants, actually the vertical walls are CLT. And part of this was really looking at a solution that would endure for, you know, hundreds of years.

This house is really thought of as this real anchor and legacy space, where the exterior facade is brick and sits on these tall, timber walls. And it creates this building that will last for centuries. That was a really important part of how we could create and really honor working with the Ronald McDonald House.

Martin: And you spoke, like moving more towards the technical aspects of wood, you spoke about how the Earth grows our food, and we need to move to an ethic where the Earth grows our homes. And, I don't know, we think that's quite beautifully put. Can you tell us a little bit more about what that means in practice for you guys?

Michael: Yeah, so you know, we're a firm that's really focused on—I think we're associated with—wood, Today we build everything we design as a wood structure. But we're really committed to the idea, broader than wood, the idea that everything should be ultimately organic, that we should move to a truly sustainable world where we can grow what we build with. Obviously, today we use aluminium, which is really hard on the environment; [it’s a] huge energy user. We use concrete, we use steel; these materials have big impacts on the planet, and they’re permanent impacts on the planet.

When you grow something, you know, it replenishes if we manage it well. So, wherever we can choose to use something that's been grown by the power of the sun, leveraging the power of photosynthesis, we want to do that. And that's not just wood; that's other materials as well.

Wherever we can choose to use something that's been grown by the power of the sun, leveraging the power of photosynthesis, we want to do that.

The interesting part of the story is that we are obviously going through massive political, cultural shifts, and the conversation of climate change is challenging all of our conceptions of the future, and encouraging us to change in really positive ways to make it better, but also really challenging ways to change industries.

And the construction industry needs to change in dramatic ways in a very short period of time. That's a responsibility we feel is on the shoulders of architects and others in our industry, to vocalize, to share ideas, to make things happen quickly, to get a little political, to get a little bit out of our bubble, and share with the world why this matters so much. And that's become a big part of us, as a firm, of how we want to communicate. We want to make an impact, not just one building at a time for our clients, but an entire industry at a time, if we can contribute towards that.

The construction industry needs to change in dramatic ways in a very short period of time. That's a responsibility we feel is on the shoulders of architects and others in our industry.

The “growing your home” thing, the concept of that, does require a bit of a cultural shift in lots of places. you know, I think when we, I spent the weekend driving from Vancouver over the Canadian Rockies, which actually, you go over many mountain ranges, and it's quite a distance, about eight hours and you see a lot of cut-down trees, a lot of clear cuts. And it can be heartbreaking to see a forest that's been cut, even for me, who believes that using wood is a really positive thing. But then I reflect on the fact that we all drive by farm fields, and we don't think twice about it. And yet, a farm field is effectively a clear cut that never got replanted.

And I think us moving to the connection of where materials come from, understanding what it means to plant something and to wait, is really the cultural shift that happens to help us embrace the idea that cutting down a tree can be bad, but it can be wonderful as a source of solving, you know, our real challenges of today and tomorrow.

Natalie: I think, too, when we look at the cycle of harvest, when we're thinking about food production, it's just much easier and we're much more familiar with that, in terms of how quickly it's replenished. What's the long-term plan? How is that going to sustain over time? And like Michael said, when we're thinking about growing our building materials, it's kind of wrapping our heads around the years that we can't even imagine just yet, as a society, but we're getting there.

There's this shifting desire and perspective to understand who made it? Where did it come from? How close is it to home? How is it impacting my local economy? And that's, very much now, the opportunity within the construction and architecture industry—that shift of perception.

And I think part of that shift, too, is really, in our food, in our clothing, in our furniture. There's this shifting desire and perspective to understand who made it? Where did it come from? How close is it to home? How is it impacting my local economy? And that's, very much now, the opportunity within the construction and architecture industry, that shift of perception and really wanting and asking for that.

Martin: Yeah, I appreciate that, and I'll push back a little bit on this concept of sustainability in timber. Because I want you to answer it, and all the ways you know how, I think. We get the benefits of carbon sequestration; it's super clear, I think, and I love timber construction for that. But what about the lifecycle and also the supply chain?

You know, I was just reading recently about IKEA, and the timber practices that some of their suppliers have engaged in, particularly in Romania. They've gotten in some pretty big trouble for deforesting parts of virgin forests in Romania, and national parks. And there's some accountability for IKEA, that they need to be a little bit better about tracing where their product is from. But can you get to some of this, how do we—if we're going to be using timber as a truly sustainable building material around the world—how do we deal with the issues of deforestation and transportation?

Michael: Yeah, [it’s an] incredibly important conversation and pretty complex one because they are typically in forest practices, well-managed, developed country forest practices, the replanting cycle and the forest management cycle, is increasingly sophisticated and increasingly responsible and is creating. A balanced forest in Europe is actually growing faster than it’s being cut down, but there's more wood being cut down today than ever. And so there is a sustainable model of forestry.

There's also a terrible model of forestry, where, in parts of the world, obviously, in South America and Africa. We mostly think about Indonesia as well, where there's deforestation that's compounding the problems of climate change, because we need the forest also to be our carbon sequestration, as part of our climate program. But in those countries, most of the reason trees are being cut down is not for buildings, it's because they're being cut down to grow crops, or worse, actually, for grazing land, in South America. That's what's replacing the forest; it's not being harvested for buildings.

In those countries, most of the reasons trees are being cut down are not for buildings, it's because they're being cut down to grow crops, or worse, for grazing land.

When we do create a wood industry that's robust all around the planet, especially areas where there's a risk of deforestation, or current deforestation, what we do is actually build an industry that encourages reforestation. So the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization that's responsible for forestry has tried to encourage countries like Brazil, and countries throughout Africa that typically cut down wood for burning for fuel, to plant forests, to aforest, which means to plant forest where trees have been cut previously, often on agricultural land. And they can't find a method to encourage them to do that.

But the answer to that problem is actually to build more in wood. When you cut down a tree, and replant it, and can make money because there's a sustainable industry using the wood to build with, it encourages reforestation, which actually, in many parts of the world, like Brazil, would mean, you could make more money planting trees than cutting them down to bring in livestock. That's the kind of formula that's really important to think about in parts of the world where deforestation is a massive problem. But in the developed world, we do have sustainable forest models; we definitely need to get better. And the example that you cited with IKEA is a really good one. Understanding the source of your wood is incredibly important.

In some countries—and Romania is a good example, Russia would be another example—it's not just a problem that the forest, the wood, is not coming from a sustainably managed forest. It's also a problem that the labor used often—and certainly, it's the case in Russia—comes from forced labor in the forestry sector. So your sourcing choices, as an architect, for wood—and that's true for every other product we choose from—needs to understand the real history and roots of where that material came from, what were the impacts on the environment? What's the impact on people, because this issue of forced labor is something we also don't track currently. And it's an important issue to be thinking about.

But the answer to that problem is actually to build more in wood. When you cut down a tree, and replant it, and can make money because there's a sustainable industry using the wood to build with, it encourages reforestation.

This subject matter is super big and complicated, it's hard to kind of summarize in a short amount of time, but you know, we believe we have to do a lot more—because we believe in using wood—we have to do a lot more to understand, and we spent a lot of energy understanding forestry models around the world. And we spend a lot of time making sure we source really responsibly; that's the most important thing all of us can do, is really understand the chain of custody. And wherever possible, use the forest certification systems, like the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), that do really help us understand the chain of custody involved.

Now, interestingly, IKEA does use FSC wood and has a very strong FSC program. So I have not heard the story of Romania for them. But it shows, if that's the case, that there are still significant weaknesses in the system. But that's also not unique to wood. That's something that every other industry in construction is also facing and needs to be addressing.

Natalie: I think one has to build on that, you know, we have these conversations internally quite a bit. And our main focus, even though we're really known as timber architects, our main focus is actually low-carbon construction, and also the social impacts. And right now, we do quite a bit of research and look at our options, when we're deciding what to build, how to build, and certainly the materials to use. And, you know, over the past decade, when we're evaluating those choices, timber and mass timber has been the clearly more sustainable option. As Michael said, it's part of considering it as the entire cycle. And one of the benefits of wood is that it already exists.

And when we're thinking about lifecycle, and the amount of energy needed to fabricate product added value, you're already well along that chain of how much energy has already been created by the sun, and the Earth, to build that material. But it doesn't stop there, right? This is a growing industry, and there are opportunities along the way to continue to kind of enhance and reduce energy consumption.

Our main focus is actually low-carbon construction, and also the social impacts.

And, you know, as a practice, we just continue to ask that question, how can we influence that bigger picture, in terms of how our materials are created? How are those products? But also, are there alternatives? As we continue to research low-carbon materials over time, there are going to be more and more opportunities to shape how we use those materials. How do we really value when we do use trees and timber? And what are the alternatives? And right now, that answer just keeps coming back to timber, but we will continue to investigate and evolve our practice with that.

Martin: Yeah, I think we appreciate, all of us, as listeners, and also [I do] as a former landscape architect, that this, like any material sourcing question or any issue in sustainability, is pretty complex to answer. So, I appreciate you taking the time to answer this one, because I believe we could do another 10 one-hour podcasts on that issue right there. And I’ve got a bunch of other questions about that. But I think one that maybe is more fun, and just today I think I answered three times. Like, ‘Oh, cool, wood construction! Well, I guess I can't smoke a cigarette near the building’, or, you know, ‘Doesn’t it burn down, if you build a wood tower?’ So, I'm sure you want a play button on your chest for when someone asks you that question, that you just sort of have a canned response. What's your answer to this?

Michael: You mean about wood burning or about people smoking? I'm happy to talk about people not smoking, too.

Martin: I’ve got that habit as well. So, no, more about the tower burning down.

Michael: Okay, fair enough. But wood burns, lots of materials burn, it's true. And the issue is, you know, thick, large members of wood actually are very hard to catch fire. And if they do catch fire, they actually burn in a very predictable and manageable way, that we can actually engineer and design around. That's the shortest version of that.

But I often use the [metaphor]—the best way for the audience to connect to the idea—I describe it as if you were to build up a fire in the fireplace or a campfire, and I handed you a big log and a lighter and said, ‘Go light a fire’, and those are the only two things you had, you probably know well enough that that lighter can't get the big log on fire, and you won't get a fire going. And instead, you need to start with maybe some paper or some pine needles, and then work your way up to some kindling, and then slightly bigger wood, and eventually put that big piece of wood on the fire. The types of buildings we're talking about, effectively are like that big log.

The member sizes, of the physical beams and slabs of wood that we're talking about, are so massive that they're very, very challenging to catch fire. And as they say, they do burn predictably. So we can engineer these buildings to perform to the same level of building code performance as steel and concrete buildings by exposing the wood and just using the scale of the wood itself as a fire resistance member. And we can do it safely. Obviously, we would never promote concepts that we didn't believe in, or didn't feel were safe, fundamentally safe. And you know, the history of this is pretty long.

These buildings help us reduce stress in our environment, improve wellness, and build very safe, very large buildings in an urban context.

This isn't as much—the mass timber, what we call the ‘mass timber industry” is a pretty young industry, of the last 20 years—as the timber, the heavy timber industry, is thousands of years old. And we have examples of 1000-year-old buildings that still stand today, in timber, that have even, themselves, gone through fires, and survived, and been repaired. But also [they] have demonstrated this kind of natural resilience that large, heavy timber buildings have to fire.

And luckily, building codes have evolved to respect and understand that, and that's why you're seeing this resurgence, especially with mass timber, which is this engineered version of wood that uses smaller trees to make big members. That's why you're seeing this resurgence of that in our conversation, not just because it helps us address climate, but also because these buildings do help us reduce stress in our environment, and improve wellness, and do help us build very safe, very large buildings in an urban context, that we need to do affordably, and effectively to solve the human need.

Martin: And how adaptable is the material as a building element? So, can a mass timber element be reused? Does it have a cradle-to-cradle construction methodology behind it? Tell us about that.

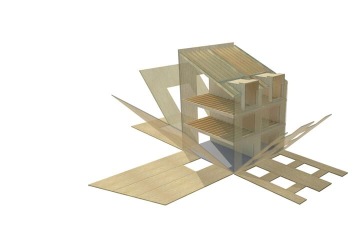

Natalie: I think we can talk and think about that on two scales. And, you know, wood lends itself really well to a deconstructable approach, in that sense, because these are elements, the mass timber columns and beams, these can be prefabricated elements that kind of click together like Lego.

So, you can imagine the reverse of that, in terms of unbolting and deconstructing, that one of the benefits with that approach is just the weight of timber is a lot less than other building materials. Thinking about how it's detailed, how it goes together, and then how simple, really, those elements can be, so that they can have another life, right? The more and more that we can think of things systematically, and appreciating that we really are going to change the way we use buildings and continue to, like we have over the course of history, how we're going to use them.

How we can think about building our buildings so simply and thoughtfully that they can have so many different lives.

In one sense, for sure, we can build them to be deconstructed. One of our big beliefs, though, is how we can think about building our buildings so simple and thoughtful that they can have so many different lives. You know, the most sustainable approach is for that building to endure for centuries and we can see that with older industrial warehouses, actually timber buildings. Our old office was an over-100-year-old timber building, and because of the nature and simplicity of those designs and inherent timelessness, both of the facade, and really the layout, they've had lots of different lives.

Through industrial [spaces], to workspaces, to residential [spaces], they have really proven that, in a way. We do that in different ways now. But I think [there’s an] opportunity for both architecture, and at the building scale, [to say] how is it reusable—that individual element? How can this be thought of as Lego?

Michael: Yeah, there's a just, to add quickly, there's a kind of romantic quality of this as well. And I reflect, around North America, and through Europe, and really around the world, there are these beautiful barn structures. And many of those have just been left to fall apart over time and collapse, and they're lovely on the landscape, but many are actually being salvaged for their wood, because that wood has this inherent beauty that we all love—we often don't understand why we love so much, but we love—and so, wood members are being picked up and turned into other things.

The mass timber that we work with will have that same legacy, not only in the way it's engineered and put together such that it can be taken apart, but also that if it was to be taken apart, the value remains.

The mass timber that we work with, in these buildings, will have that same legacy, not only in the way it's engineered and put together such that it can be taken apart, not only that it has this long life that Nat talked about, but also that if it was to be taken apart, the value remains. And I expect the same thing will happen, just like a barn, that people will salvage these members, and rebuild, and build new things, because the wood is far too beautiful to abandon.

Natalie: And all the while, those pieces contain carbon, right? What's so fascinating about that potential, of the different forms of life of these materials, is that throughout that whole process, these are kind of carbon storage banks, right? And we use them in different ways.

Michael: No, it's just not the case. I mean, I can't speak to the buildings others are doing. But, you know, one of the things we believe in is that part of sustainability is affordability. And as we've invested a lot of time into the research and development of ideas, as much of our effort has gone into how to do this sustainably, as how to do it affordably. That's a core value for us, as a practice, and we know that changing global systems, towards something more climate-sensitive, like this, requires it to be cost-competitive.

And in fact, we, currently in Vancouver, believe that we can do these buildings for less money than concrete—not a lot less money than concrete—but our concrete industry right now is pretty busy and pretty competitive. And concrete is getting expensive, where we live in Vancouver. So, here, we believe we can start to build these buildings for a little bit less than a concrete building.

One of the things we believe in is that part of sustainability is affordability.

In different cities and different places around the world, that story will be different. It depends on the cost of labor, the access to steel or concrete, versus wood. There are a bunch of variables, but there's no question that the future of this way of construction will be completely competitive, cost-wise, with concrete and steel. And that'll come from maturity of the industry, competition in the industry, and the understanding and sharing knowledge, globally. That is, in our minds, an inevitability all around the world.

Martin: I think one of the cost savings, that I would argue is really beneficial, is the transport. You can reduce the number of trips to a construction site dramatically because of flat-pack panel construction, built out of timber. And the prefabrication, I think, also pushes, or condenses, construction schedules—do I have the correct understanding?

Natalie: We are heavily invested in off-site construction, in general. And, definitely, we look at what we can do off-site, prefabricating wall elements and floor elements, having that in a controlled environment, and being able to take advantage of the economies of scale, in terms of really thinking about affordability in a real way.

We look at what we can do off-site, prefabricating wall elements and floor elements, having that in a controlled environment, and being able to take advantage of the economies of scale, in terms of thinking about affordability in a real way.

Then, just like you said, there's that ability, then, of showing up to the site and having a lot of that work already done. So [it’s] definitely saving time and also creating a quieter [site and being] more of a good neighbor. We like to talk about it in the sense that it can be a very pleasant experience. And, certainly, any kind of construction site is exciting, but the ability for that to be also—if you're living right next door, you get not only to see that kind of wonderment going up—it's also not disturbing the immediate neighborhood, both in terms of time and also in terms of sound impacts.

Michael: Yeah, time is the big one, right? So, when we talk about affordability, time and predictability of schedule is something that the industry really struggles with. And these buildings can be built far faster than steel or concrete buildings, especially concrete. And time is money, so that is part of the formula that we're always working with.

As Nat said, impact, right? So, when we talk about the cost of buildings, there's a whole number of costs that never get picked up. One of them is carbon; we don't tend to pay the price in carbon impact, which we should. The other is, as Nat said, noise and disruption. Streets being shut down for concrete trucks has a huge cost to the community, or to a business down the block that has to put up with that traffic. There's no actual cost attached to the cost of construction, for those kinds of social impacts and economic impacts to others.

When we talk about the cost of buildings, there's a whole number of costs that never get picked up. One of them is carbon; the other is noise or disruption.

Fast buildings, wood buildings, allow us to start really reducing those uncaptured costs, that as a society, we need to actually start to own a bit more responsibly. If the mental health of the neighbor, because they're having to hear loud steel construction for nine months, is being impacted, where's the cost of that being captured by society or by the building itself, these wooden buildings give us a chance to really start thinking about those issues and making them better.

Martin: In that sense, it sounds like timber construction at scale has a lot of benefits to add to the affordable housing crisis and the need for building housing in lots of our cities, including European cities, which struggle with affordable housing and availability of housing in downtowns. So, you see this very much as the downtown, center city building material, and you think it will help us solve the affordable housing crisis?

Michael: Yes, but not alone. I think, the most, in our minds—and this is why we invest a lot of time and why we're partnering with Katerra, here in North America—off-site construction is the critical part of affordability. We currently build the way we did 100 years ago largely, with very modest changes in the character of construction, globally. Compared to 100 years ago, the evolution to offsite construction really allows us to engineer design differently, engineer away waste in the design, as all other manufacturing happens. And, you know, by doing that we're engineering away costs and reducing costs.

Off-site construction is the critical part of affordability.

What's interesting, when we look at off-site construction, especially in urban contexts, where you need robust materials to build large buildings, we really have come to believe that this is the other place that mass timber becomes the most exceptional material. And that's because steel and concrete are very heavy materials to build off-site with, to lift panels onto trucks, and drive them to the site, and lift them into place. It's very expensive with heavy materials like those.

Light wood frame, or light steel frame, construction is a little too flimsy for a lot of big buildings. You know, you can't build a very large building with those. And also, when you're transporting them to the site from an off-site location, they can be so flimsy that you can't fully finish them with plumbing, and finishes, and so forth.

Mass timber sits right in the middle, it's robust enough to be moved really well to site, but it's also light enough that you can transport it to site and lift it into place.

Mass timber sits right in the middle, it's robust enough to be moved really well to site and be a completely finished panel. But it's also light enough that you can transport it to site and lift it into place. So, as we think about reducing costs, as we think about moving towards off-site construction, mass timber just sort of resides in the perfect sweet spot of where we think we can tackle exactly what you talked about. It’s [tackling] increasing issues of density in inner cities, but also doing so in a much more cost-effective way.

Natalie: I think, as Michael mentioned earlier, there are opportunities across the typologies. And, right now, the sweet spot in North America, when we're talking about cost comparison and affordability, is in the higher range, so kind of ten-plus-stories [tall], and that is because it's been comparative from a cost perspective to other materials like concrete and steel.

When we look at other typologies, certainly lower rise and even more remote locations, the ability to think about how the material is transported, how we take advantage of that kind of lightness but also strength, it exists within smaller buildings as well, and in some ways, offers a really rich opportunity to take advantage of the experiential qualities.

How can we think about these opportunities of off-site construction within that building type, to provide the most responsive and sensitive solution?

So, I think one of the items we haven't touched on yet is the beauty of not having to add a lot of finishes. And when we think of that, the natural material, this the structure itself, being the interior experience; that's true amongst all kinds of different building scales.

And we've explored this in smaller townhouses—as you can see in Ronald McDonald House, that's actually a much smaller building scale, up to four stories, and was successful for kind of a wide variety of reasons, of the benefits of timber—and so, you know, the answer really relates to where are you in the world? Where are we in the world? What are the alternative building materials? And how can we think about these opportunities of off-site construction within that building type, to provide the most responsive and sensitive solution? And that can exist in mass timber for a range of building scales.

Michael: In our practice, I think we are often talking about tall wood, we really largely leverage tall wood—as a way to push the engineering conversation to create a global acceptance and almost global race for ideas—which, in a way, was captured by that idea that tall is exciting. But the truth is, in our practice, an enormous number of our buildings are mass timber, but 1, 2, 3, 4 stories, and ranging, as Natalie said, from public libraries, to art galleries, to gymnasiums, to public swimming pools, and, you know, small resorts, and smaller residential buildings.

In North America, we don't build a lot of single-family homes in mass timber. We do some, and they do tend to be higher end. And that's really because our culture in North America around light wood frame construction—what we call a ‘light wood frame’, which is really the dominant construction type for smaller buildings here—is extremely cost-effective. And it's challenging for mass timber to be competing against light wood frame, where light wood frame is allowed. But light wood frame isn't allowed on bigger buildings. And so that, again, is where mass timber starts to become really cost-competitive. And light wood frame isn't as effective for public buildings, so that's also where it becomes really effective.

Martin: So the perception's changing, at least from what I can tell. And also, I think, the technology is changing in terms of how many suppliers we can find for mass timber. I remember working as a landscape architect in Calgary on a bunch of projects and at the time, I don't know, even 10 years ago, it wasn't so easy to find this kind of timber. There are a couple of suppliers in BC, British Columbia, that were supplying it, and a couple on the East Coast, as well. But I guess, are perceptions changing in the public also, are client perceptions changing? And are you finding the availability, [to have] more options in the market?

Michael: Yeah, I mean, we're really lucky. There's been a huge change in the last five years around the supply chain. So, whereas for quite a long period of time, for the last 15 years, really there were only two Canadian suppliers for all of North America. Now you have a host of new suppliers coming into the US. You have the Canadian suppliers actually opening up CLT plants in the United States. And groups like Katerra, who again we have a partnership with, have built the largest cross-laminated timber plant in the world, in Washington State.

We are often talking about tall wood, we really largely leverage tall wood—as a way to push the engineering conversation to create a global acceptance.

So, now with that level of material production, the issue isn't really the supply chain. Now it becomes a demand chain issue. And the demand chain comes from a couple of different places. One is consumer education—I think people know that there's an alternative way to build an alternative home for them to live in, and all the benefits that come along with that, especially around wellness, and obviously climate—but also demonstrating examples of it.

So, we're huge fans and supporters of anybody that's diving into this industry, and the architects who are choosing to work in the material. The best part is that there is just a hugely-uphill spike in popularity right now around mass timber, not just in North America. So, we really expect that the consumers increasingly are going to demand these kinds of buildings, and that'll be great.

Martin: I'm really enjoying the conversation so far. And I love the conversation about wellness and how timber can help us with the way we feel in buildings, and also how it's going to help us solve the climate crisis. A lot of these ideas came through, I think, in a competition that Michael was the chairman of the jury for, the competition was called City Above the City. Can you explain what that was? And maybe some of the ideas that were inspiring, which came out of that, Michael?

Michael: Yeah. So there's a neat company, a large forestry company called Metsa, out of Finland, that was inspired by the idea of stimulating conversation around the world through competitions, and through some pretty neat exercises to see what wood could do, especially to some of the iconic buildings. What if they were built in wood? So, they've been doing these sorts of fun exercises, and we've been involved in a few of them.

The City Above the City competition was a competition for architects and students to come up with ideas of how do we densify? How do we take a city like Berlin, and instead of just tearing buildings down and building new buildings, how do we add more density to existing buildings? So, the concept was really about the fact that mass timber has that unique quality of being both strong and light, you know, reasonably light, let's say—it's not light. Therefore, you could add a floor to the tops of buildings without requiring all new foundations to support the weight of the building. And you could do that in a way that's safe, from a building code and fire safety point of view, and a structural point of view.

We're still in a time where our building culture is one of tearing things down and rebuilding.

And so the idea was to kind of stimulate that conversation, what does the future of the city look like if we don't keep tearing buildings down and building bigger ones? And the ideas that came through were amazing; you know, as with any competition, they were all over the map. And they ranged from really simple ideas to really, really huge, complicated ideas that perhaps were stretching the limits of imagination of structure. But what it did was exactly what it should do, which is just broaden the conversation to say that there are so many applications where this new material can be applied.

This is an important one that can solve a really serious issue, especially in cities, like European cities, where the infrastructure and the existing building stock is good, but perhaps [we] need to add density to it. I think in North America, sadly, we're still in a time where our building culture is one of tearing things down and rebuilding. I think Europe has a unique opportunity to show us the way that preserving and building in addition, like the competition did, is a better path forward, where we retain structures and all of the embodied environmental impacts of those structures.

Martin: One of the projects where I think some of these principles were exhibited really well was Sidewalk Labs' Quayside, in Toronto. You were part of that project, right?

Natalie: Yes, we were.

Martin: We presented it with Thomas Heatherwick at one of our conferences. And then we also had the other side of that argument arosund the project, about data security and transparency on the project. So we've dealt with this issue before. And I, personally, was so excited about this project. I know the guys at Sidewalk Labs that were running it. I know Dan Doctoroff. And I thought some of the initial principles were interesting. And we had never really approached city building like this before.

I was particularly excited about the way they talked about sustainability, the way they talked about using better building materials. I liked having a kind of networked city. There were lots of thorny questions about the data ownership and stuff like that. And I did like the innovative way they were thinking about financing it. But of course, there are lots of questions that came up, which eventually killed the project, recently. So, I think that's pretty well documented, but tell us about your participation in the project. Did you learn something? Are any of the ideas that you pitched to them, or that you were working on, are they moving forward? Are you gonna use them somewhere else? What's going on there?

Natalie: I think, as you mentioned, there are so many compelling aspects of the approach that Sidewalk Labs took; it was a massively ambitious endeavor. I think in that ambition, [we were] asked some questions, that we in the industry, and within our communities, we need to be talking about right now. And our involvement had two phases.

How do you create a sustainable building stock with repeatable parts, but really allow for diversity of expression, and diversity of different points of view, from a design perspective?

The first was really about, ‘Hey, look, there's a massive opportunity to create a timber neighborhood at scale’, and thinking about that as a kit-of-parts. So, the question of how do you create a sustainable building stock with repeatable parts, but really allowing for diversity of expression, and diversity of different points of view, from a design perspective? So, from the beginning, we were part of the team and really led the development of the mass timber kit-of-parts. That was then tested by architects around the world to say, how could this recipe book or different array of components really come together in a variety of ways to create diversity of experience?

And, for us, one of the really compelling themes of the project, and the effort, was that it expanded well beyond one building. The network of public spaces, the idea of multi-generational living, the idea of different uses being built together, and thinking about how overlapping those, de-siloing of the uses, could fit within one neighborhood.

So, our first effort was really about working with the Sidewalk Labs team and the greater project team to develop that kit-of-parts playbook. And asking the questions, not only about the mass timber part of that kit, but also the other components, like wall panels. How could we think about a floor plate that could evolve and change over time—there's a couple that has a child, but then an older family member moves in—how can that residential unit really grow and change, along with the way that we live and the way our family structures are changing. So, that was our first endeavor.

The network of public spaces, the idea of multi-generational living, the idea of different uses being built together, and thinking about how de-siloing of the uses, could fit within one neighborhood.

And then the second was working with Sidewalk Labs on really proving out a prototype of a 35-story tower, from a code, some building code, technical, and also constructability [standpoint]. So, it was an opportunity to get a lot more detail on certain aspects of what made that timber tower unique to traditional construction methods. And that was, working within the parameters of building code, how to work with the local government and find those solutions, to address that opportunity and challenge.

So, the two roles that we played offered different opportunities to engage in that conversation. I think that beyond just ourselves, one of the really compelling aspects of that project is how widely shared the process [was], the takeaways that Sidewalk Labs released to the general public. And, you know, we're big believers in sharing ideas and building on those ideas together. And that's actually a really good thing. Sometimes there can be a sentiment in design that, ‘That was unique, now we have to do something totally different.’ But with mass timber and this evolving industry, there is this real cultural approach to sharing ideas and celebrating that.

Martin: Yeah, I think you hit a lot of the points that I was excited about for the project. And it's a really interesting approach from Sidewalk Labs that they took. As an urbanist, which is what we consider ourselves here at reSITE, I was super excited that they were approaching lots of different industries and saying, ‘We want to build a city in the way that you imagine cities.’

So, for you guys, it was mass timber construction at scale, at the neighborhood scale. For technologists, it was the fully networked city. For people interested in sustainable energy or renewable energy, you know, there were initiatives for them. So I really appreciated this super ambitious approach. I think that they probably, knowing who was running the project, underestimated the fact that not everyone was as excited about change as they were.

I think that was one of the, maybe, “hiccups” that they didn't realize would come—that they needed to deal with communication with the public in a better way about the data side of the project. [It was] kind of disappointing that it failed. But I think, as you said, lots of things can come out of that. And now, I think people are talking about timber scale neighborhoods. And I think that's a good thing.

Architecture is going through this exciting period of shifting from that ‘master vision’ kind of concept, to a more collaborative, process-oriented approach.

So, knowing that we're sort of running short on time, I want to maybe jump to the last segment. There's been some interest in gender diversity in architecture. And I appreciate this conversation, because I hear two really sensible people talking about design and sustainability, both from different perspectives. Natalie, can you illustrate some time in your work, where you think that a purely female point of view has added a certain sensibility to your design process, or to the projects that you're working on?

Natalie: Yeah, I think maybe I'll tackle that from, as you said, the way that Michael and I have developed to work; [there’s] really an aspect of, not only that we’re male and female, certainly, but we have different perspectives, for a lot of different reasons. But we deeply respect one another, and welcome and encourage debate and different perspectives to challenge each other. That learning has taken shape in lots of different forms, throughout our almost 15 years, now, working together. And a part of that is our different genders, but I think it's also just different points of view.

Within our practice, we're deeply process-oriented, and within our team also, the balance of genders has always been a really important part of our office structure. I think what we've observed is it can create a kind of environment that nurtures collaboration with that balance. And thinking beyond our project teams, it’s a fact, the construction industry as a whole is very male dominated. And when we look at the larger clients, and the leadership coming to us, there's still quite a skew in terms of the voices [toward] the male perspective.

Michael: Yeah, there's something—from the inception of our firm, we've always been 50/50 or, from time to time, more women than men—something really wrong with our industry, that it's notable. But, but we do notice, for sure. That should be the norm; that shouldn't be a special thing. But 'how do you build for society if you don't represent the voices of society?' is the way we see it. And it's not just about different perspectives of the sexes, but different perspectives of age, different perspectives of race, and sexual orientation.

And in the microcosm of our office, just observing how valuable that balance is, it’s something that we just continue to invest in and also seek to expand, going beyond just male and female, all different types of diversity of voices. Architecture is going through this really exciting period of shifting from that ‘master vision’ kind of concept, to a much more collaborative, process-oriented approach, which doesn't mean compromise. It actually means taking advantage of different perspectives to build on them, where the idea of like, two months together can equal five [apart], if we're building on that, and I think we invest in that kind of concept really deeply. And we certainly appreciate that Michael and I have different perspectives and life experiences, and part of that is gender.

How do you build for society if you don't represent the voices of society?

The full diversity of issues that we deal with in society should be issues we're both addressing through design, but should come from a process and a collaboration of people that actually represent that diversity of views. So, we constantly want to increase diversity. But in a weird way, this balance we have between men and women in the firm is strangely unique. It's also just what should be the case in the entire industry. And we know that it's part of our success, that we care about this balance and diversity in our practice. But it is strange, that is something that we do recognize we're quite unique in the industry for.

Martin: I think any of us who’ve sat at a table with real estate developers, or clients, or municipalities, or planning commissions know that the testosterone level needs to be lowered a bit. I always felt really strange at these tables that were dominated by men and I always worked for a woman-owned firm, before I left to do reSITE. So, I always felt really strange for the owner of our firm, who had to sit at these tables. I really appreciate this level of discussion. I think it is remarkable, what you're doing with the gender balanced firm or how you're approaching projects. I feel very similarly, that this shouldn't be remarkable. But it is, and I think you should be proud of that.

I think it's one of the ways in which we can start to build rings. And I think this is where architects have the responsibility to grow the rings, as you discussed, that can help, let's say, give us a better process and protect the diversity of the city. Maybe [I’m] stretching the metaphor a bit, but I think it helps, having this diversity of views for projects, and particularly for architecture. And [do you have] any last points on this, or anything else that we missed today?

Michael: You know, one of the things that we also feel is important is to constantly check in on ourselves, on what we're doing well, and what we're not doing well, and really own the concept that we can improve. There are areas around this issue of diversity that we're working on improving, and one of them that we feel is really important, as Canadians, and in our part of Canada, is to really develop a stronger connection to our First Nations people, our Aboriginal community, and see representation from that community in our process, in our work, in a much better way.

We feel it is important to constantly check in on ourselves, on what we're doing well, and what we're not doing well, and really own the concept that we can improve.

And it's an area of decolonization in our practice; that's something that's become really increasingly important. And it's something that, truthfully, we neglected for too long. So, we see all these areas for improvement, and we try to share the idea that we're getting certain things right, but we've definitely got a ways to go, as a practice, to keep getting better. And hopefully, everybody else sees that within their own practice.

Martin: Yeah, agreed. And I think this gets to the point of all of us having the responsibility to grow the rings and create a more inclusive environment, to be more open, be more friendly. So, I really appreciate this conversation. Both you and Natalie, thank you so much, Michael, we really appreciate talking to both of you and learning more about your practice, your expertise, and particularly, I enjoyed the conversation about the sensibility in which you bring to the design process.

So thanks so much, and and I hope you hope you're all doing well.

Michael: Great. Thanks so much for having us. It's really fun to chat with you.

Natalie: It was a great conversation. Thanks a lot.

Michael: Have a great day. And thanks to the audience for listening.

Michael Green + Natalie Telewiak, Founder + Principals of Michael Green Architecture located in Vancouver, BC

What we can draw from this conversation, as Martin said, is that we hold responsibility—for our environment, for our communities, for each other—they are the factors that build rings of support and inclusivity into our cities.

Another takeaway is that sustainability is a deeply complex issue, but it is not unsolvable. Just as we’ve begun to care more about the sources of our food and our clothing, we should apply that same mindfulness to how we source the materials that build our spaces, and our communities.

Natalie and Michael’s passion is evident and inspiring. We hope you’ve been energized by these changemakers and their vision of a healthier, greener, and more equitable world. MGA’s leadership and commitment to the use of natural, renewable materials can set an example for city-makers working to provide a brighter future for generations to come.

This episode was directed by Elizabeth Mills and produced by myself, Alexandra Siebenthal with the support of Martin Barry and Radka Ondrackova as well as Nano Energies and the Cech Ministry of Culture. It was recorded in the reSITE office in Prague and edited by LittleBig Studio.

Listen to more from Design and the City

Michel Rojkind on the Social Responsibility of Design

reSITE's podcast, Design and the City, features Rojkind Arquitectos founder, Michel Rojkind in conversation with Martin Barry on how he uses design as a tool for social reconstruction.

A New Generation of Architects with Chris Precht

Chris Precht’s aim to reconnect our lives to our food production by bringing it back into our cities and our minds can be found throughout his architecture. Listen as he discusses the importance of authenticity, creating spaces that activate our senses, and looking at our objective reality to solve the problems of our time.

Giving Design a Higher Purpose with Ravi Naidoo

Ravi Naidoo, the driving force behind Design Indaba, arguably the most influential design event in the world. The event takes place annually in Cape Town is only the tip of the iceberg. Listen as he pushes the boundaries of the purpose design holds with the simple question—what is design for? Photo courtesy of Design Indaba

Creating Emotional Connections to Nature with Yosuke Hayano

Yosuke Hayano, principal partner for MAD Architects examined how the studio approaches every project with a vision to create a journey for people to connect with nature through architecture. Listen as he draws on specific projects that embody that connection on a macro and micro level. Photo courtesy of MAD Architects