Trey Trahan on Building Sacred Spaces for Connection

This episode of Design and the City features the founder of Trahan Architects, Trey Trahan on the importance of creating sacred spaces devoid of clutter that make way for that human connection, his definition of beauty, and the potential regeneration holds, presenting a different side of that coin.

“I think that buildings should possess a variety of spaces and should be designed to encourage meaningful human-to-human engagement, human-to-the-natural world engagement, and even spaces for self-reflection.”

Listen to Trey Trahan on Design and the City:

For Trey Trahan, founder of Trahan Architects, human connection, ecology, and unvarnished beauty encompass the core ethos of his work which primarily focuses on creating cultural architectural spaces. With roots in New Orleans, and their global perspective based in New York, they have risen to the rank of the number one design firm by Architect 50, an official publication of the American Institute of Architects. He leads his firm with the conviction of bringing humility and awareness into a mindful design process to create authentic spaces that elevate our lives and the human experience.

His firm known for projects like the Holy Rosary Church Complex, St. Jean Vianney, Coca-Cola Stage at the Alliance Theatre, as well as the Louisiana State Museum and Sports Hall of Fame and the Mercedes-Benz Superdome renovation post-Katrina, just to name a few. As well as his poetic approach and thorough consideration applied to every aspect of his projects.

He views them as part of the natural ecosystem, including the soil. Soil is the repository for all living, organic matter, and for Trey, our buildings should not be separate from it, but constructed in harmony. And, well-constructed spaces foster human connection, both ephemeral and lasting—and it should be no different between architecture and the natural world.

We connected with Trey to hear his ideas on the importance of creating sacred spaces devoid of clutter that make way for that human connection, his definition of beauty, and the potential regeneration holds as he presents a different side of that coin. His primary focus is creating lasting, impactful cultural spaces, with the aim to look at the periphery, examining how architecture builds connections between humans and the environment in ways we may have not considered.

Alexandra Siebenthal, reSITE: Hi, everyone. I'm so excited to be here speaking with Trey Trahan. Is it Trahan; am I saying it correctly?

Trey Trahan, Trahan Architects: Well, it's interesting in South Louisiana where the French people live, it’s Trahan, but I've been referred to as Trahan outside that part of Acadia Parish.

Trey: Yeah, so Trahan or Trahan, or whatever, yeah. Quick story, and then we'll move on. So this elderly consultant came to the office one day, and we met, and he gave us advice about a project type. And as he's walking out, Alex, he's walking out similar to an actor by the name of George Burns in the movie, Oh, God!, I think that was his name—he was kind of shuffling. And as he walks out, he says, Trahan is music, Trahan is not. And it just kind of hit me deep within, because he was suggesting that people were pronouncing my name incorrectly, and that it felt dull and flat—didn't have that kind of cultural richness to it. So anyway, whichever you prefer.

Alexandra: No, no, I appreciate the background so much, so I will try it with, Trahan.

Trey: Yes—sounds much more beautiful coming from you!

Alexandra: My French studies… Okay, so founder of the award-winning Trahan Architects, and I think we have a pretty interesting conversation lined up, so Trey, thank you so much for being here.

Trey: Thank you, Alex. It's a privilege to be with you today.

Alexandra: Thank you, I appreciate that so much. So I want to just kind of start from the beginning. Tell us about your background, where you grew up, how you got your start in architecture, and I'd love to hear also how your upbringing influenced you.

Trey: So I grew up one of four kids, I was the second. My father is French, my mother is Czechoslovakian, and I grew up in a very rural and small town of Crowley, Louisiana. The town professes to be the rice capital of the world, which is somewhat suspect, but it is a beautiful place. They refer to it as the Acadiana prairie, because it was the French that left France obviously and moved to Nova Scotia, and then moved southward to Louisiana. It was a beautiful place to grow up—there is a real openness and honesty there—a place with tremendous integrity. A place where, looking back, there were two basic crops. There were a lot of farmers, people grew rice and soybeans, and that was because the clay content in the soil provided a kind of “pan” condition where you could flood the fields and grow rice.

As architects, we're dealing with a material world which is a measured world, and what I think of as an immaterial world that's immeasurable.

So yeah, I remember growing up along the bayou, which is our “dirty stream'', so to speak, because of all the sediment suspended in the water. I made this connection years later as I was playing in the woods because my mother would introduce the idea of me getting out of the house with three sisters, because of how disruptive I was. I remember watching a crop duster, an open-cockpit crop duster, flying across the bayou because there was a farm on the other side, and seeing that the pilot in the cockpit, but also seeing under the belly of the small plane, this nozzle where I have to believe, there was some type of horrific pesticide. As I said, it wasn't until years later when I made that connection of how bothersome that was, that I was even potentially being sprayed by that crop duster.

I remember years later speaking to my father about it. In the discussion—and this was at a time when the black birds were coming back—he spoke of how once we discontinued the use of these chemicals, that black birds returned in these massive waves as they kind of dance throughout the sky. So I think all those things, whether we're conscious of them or not, in time we make those connections. Yeah, and so I think that had a profound impact—playing in the woods, so to speak, and building cabins and finding discarded or fallen trees. And in the woods there, in the swamps were the cypress trees, which had the Cypress knees, which you connected, intellectually, that the tree root system would then emerge up and create this kind of small city—this kind of pixelated place of Cypress knees.

Alexandra: Wow, it sounds idyllic. When I was researching you, New Orleans just sounds like, I don't know, out of a book to me or something. It's so poetic and lovely, so thanks for sharing that. You brought up the soil and the clay content and I know this is a big topic you're eager to speak about. Why is soil such a focal point for you?

Trey: Yeah. Well, I've always, even in school struggled with, 'How do we, with integrity, authenticate our work?' What does that search for?’ Well, I began thinking about it, I started at a certain point thinking, because I have to edit things down in my mind, that it's really simple. As architects, we're dealing with a material world which is a measured world, and what I think of as an immaterial world that's immeasurable.

And so when I think that way, as opposed to a building in a context, it liberates my thinking to question an appropriate balance and hopefully a beautiful relationship that is not about dominating a place, but something that has a rich and meaningful dialogue between natural systems, and the seriousness of the building—of placing anything in a landscape on the planet. It shouldn't be taken lightly, right? It's an awesome responsibility. And so my search, our firm's search has been: it has to be more than just adjacent buildings and materiality—there has to be more.

It liberates my thinking to question an appropriate balance and hopefully a beautiful relationship that is not about dominating a place, but something that has a rich and meaningful dialogue between natural systems, and the seriousness of the building—of placing anything in a landscape on the planet.

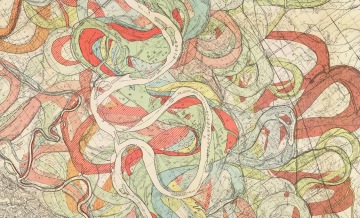

And so as I began to think about and learn more about watersheds and realise that Louisiana is at the end of a watershed that begins in multiple provinces in Canada, and covers a large percentage of the US from Continental Divide the Continental Divide, I think a lot about ‘Wow, what are the different cultures, the indigenous people that occupied these places? What is the soil like? What are the seasonal aspects up North? Fallen snow, the melting of the snow, that movement of precipitation through many tributaries to the Mississippi—all different soil types, mixing together, each with different characteristics, and some falling to the bottom of the river, some being suspended in the water, and those participating in a process of depositing and scouring’.

If you're ever interested, look up the Harold Fisk maps. They're beautiful maps that represent the ancient meanders of the Mississippi, pre-levee. It's amazing how dynamic this river is and how it literally moved throughout the landscape and introduced different soil types. And so then you begin to make connections, especially coming from Crowley of, 'How do we cultivate these soils?' What does that mean when we cultivate a place—to food, cuisine?’ And of course, you make connections to culture. Then you realise that some soils are healthy and some soils aren't, and what does it mean to work on a site with healthy or unhealthy soils? It's all of these connections that I am just deeply moved by and interested in—it's that curiosity within. And how are they affecting who we are—our convictions and how we contribute to others—in important ways?

Alexandra: I really, really love this metaphor that you're using and I've seen it a lot lately—especially as we're kind of coming out of the pandemic and moving into a whole new, let's say era, and hopefully not going back to the way things were—that there is the same sort of regenerative quality that I find with soil. It's literally where life comes from and where it ends, or put another way, a source of sustenance and vitality that comes from food. I think it's super fascinating to apply this in terms of architecture, and also maybe being conscious of, and being mindful of that as a resource for how you're building architecture, if you will. How do you plan to use that in terms of building structures? Is it about just surveying the ecology of the area and applying that, or is it actually physically using soil to create buildings?

Trey: Yeah I think it's both and others. The earliest structures in Louisiana, by the indigenous people and then the early settlers in the early 1700s, were buildings referred to as bousillage, which is clay, horsehair and moss. It's kind of a version of adobe. It's sometimes referred to as 'throwing in the cat,' which I find interesting because they would erect timbers and sometimes it was poteaux-en-terre, the post embedded in the soil. Then there were slightly diagonal, horizontal members and they would mix in the ground clay, horsehair and moss where the black inner thread was removed. And they would create these loaves of bousillage and then stack it, and then it would hydrate. What was beautiful about that is the hydration would leave a slight crevasse, a separation between the mud and the wooden member, and it was like an early form of outside air. And so they were just beautiful.

So there's that physical use, but I think soils are much more than that, because when we think about them, we think about a healthy soil with a certain density of organic matter that has a level of nutrients in it. Those nutrients, the fertility of that soil, is passed on to plants that we eat and that contributes to a degree of health, but healthy soil also results in, or can, result in a healthy economy, and a healthy healthcare system.

It doesn't mean at times some are going to privilege one form of life over other others, but I think we have to be respectful of all forms of life. I think there are deeply meaningful connections between buildings, architecture, and soil.

I mean, I think you can begin to extrapolate all of these, because you have to think about it in terms of cover crops, rotation of crops, and then we begin to think about protection of topsoil. I think I once read that it takes 1000 years to build three centimetres of topsoil. And so there's this precious layer that we build on, we almost encapsulate it recklessly in my opinion, that almost has this, this sacredness to it, because embodied in it is life. And embodied in the soil, healthy soil, are so many different forms of life, from beetles, bugs and worms. If we really want to, I think live healthy lives, we care deeply about all forms of life.

It doesn't mean at times some are going to privilege one form of life over other others, but I think we have to be respectful of all forms of life. I think there are deeply meaningful connections between buildings, architecture, and soil. I think that will reveal itself more and more by the use of technology. I, apologetically, initially thought of technology and advancement separate from the natural world, but I'm a believer that the advancement of technology if allocated properly, can contribute significantly to biodiversity fighting climate change, and beautiful soils, soils that contribute that aren't experiencing runoff.

You take, for example, Louisiana. We're losing a football field of land every one to one and a half hours, and that's because we have leveed the Mississippi River, and the process of fresh water distribution and sediment replacement has been lost. All of that is gone off the continental shelf. And so what's happening is, without the replacement of fresh water, the salt water is moving up. It is resulting in the degradation of flora and the loss of land. And so once again, soil and land—they're important.

Alexandra: How do you think this plays into sustainability, especially with climate change and Louisiana itself being most vulnerable? When most people think of sustainable or green buildings they think of the structure itself, and the energy it's using instead of the surrounding areas you're suggesting. What sort of responsibility then do architects have, and how can architects apply that responsibility and build with care?

Trey: Yeah, I think that's a great question. Well, I think as we're experiencing some degree of global warming, and more and more natural events that are devastating to our communities, the cost is overwhelming. We've probably reached a point, if not, we'll reach a point shortly where we just can't afford to rebuild communities along the coast. That's very unfortunate, because there are a lot of rich cultures along many of our coastlines in the US and internationally.

I think that we can continue to build far away from the coast in sustainable ways, but I think at a certain point we're going to have to deal with the efforts of lobbying, and oil and gas, and these entities that we've all benefited from for many years. I think we've reached a time where we have to say, look, we're appreciative of your many contributions, but the truth is you contribute in many ways that elevate the quality of our life, but reciprocally we can't tolerate it—we need to address this. So I think we need to confront reality and deal with the truth, and I think that's where it begins—dealing with some of these issues along our coastlines.

Alexandra: And what about in a more urban context? How does soil inform design or your building process there?

Trey: That's a great question. For me, as I mentioned earlier, we tend to encapsulate all of this topsoil on earth. It just seems like we need to daylight our city, so to speak, you know, return—I love when we stumble upon a building that is no longer occupied. Even if it's concrete, or brick, or masonry or stone, it's amazing how the natural world begins to reclaim it. We talk about integration of the natural world and the built world—I think that's the most powerful precedent—this abandoned building that has a plant growing out of a stair or through a skylight, or through a window. That's kind of the physical expression or relationship that I find most exciting.

I love when we stumble upon a building that is no longer occupied. Even if it's concrete, or brick, or masonry or stone, it's amazing how the natural world begins to reclaim it.

Maybe a process of building is building on an armature and stopping before completion, and allowing the natural world to have a voice and gain some foothold—and then respond again, in completion of the building. I think healthy soils would be integral to that, because I think you would think not in terms of independent silos: the building, conditioned space, and the outside world.

I think what would come about is what I find beautiful about New Orleans. There are degrees of "outsidedness". And that kind of gradient is what's powerful, because depending on environmental conditions, you could define that as a place of comfort, as opposed to internal and external. I think that's where meaningful human-to-human engagement happens—in those kinds of spaces.

Alexandra: Do you see nature as something to learn from more, or mimic?

Trey: Yeah, I think the least we can do is mimic, but I would hope that we would learn from it because it does teach us everything we need to know about life and death. It gives us life, and of course in New Orleans, the ceremony of funeral—especially in the African-American community, is beautiful. I mean, that processional aspect throughout the city, but also our cemeteries are little built cities, right? People are buried above ground.

So I love that aspect of ecology, but I also like thinking about, for example, a nursing log. When a tree falls in a forest it opens up the upper canopy and it falls on the ground, and it becomes this decaying armature for more growth. I think there are many lessons that are embedded in that process—in the act of death of something, the decay of something, is the privilege of new life. And maybe in some ways, although really sustainable, when we build with such a long-term commitment, maybe there's something lost in that, and maybe a building should have an age. What we should pursue, as far as the length of life of a building maybe should be less, so that we actually allow it to decay and become an urban forested area—a small park and ensure that there are financial incentives to someone after so many years to let it go.

When we build with such a long-term commitment, maybe there's something lost in that, and maybe a building should have an age.

Let it contribute to the quality of natural light in an urban setting, the quality of air in a natural setting, a safe place, if handled correctly, for families and kids to play—for levels of engagement. Something is significantly lost when you're relegated to 24/7, 365 urban conditions that are all about hardscape, and lack the ability to reach down and pick up the soil, or even put a blade of grass in your mouth or whatever—touch it, engage with it.

Alexandra: When you say “buildings should have an age," such a statement seems to contrast our understanding of lasting sustainability in architecture, so what is the benefit of assigning a definite lifespan for those structures?

Trey: Additionally, I think we should think about a diversity in the age of buildings, should we think of an urban context, in terms of buildings that are designed with materials that have great longevity of permanence. And, in contrast, design buildings with materials and systems that have a far shorter life to them. And then some that reside somewhere in between. And so similar to a natural forest, maybe some that die early in their lifecycle, they are acting similar to a nursing log, where in their decay or degradation, they are contributing meaningfully to maybe small urban parks, maybe providing in some way similar to the natural world, nutrients to community, to places, but I'm not suggesting that all buildings are designed with such a short lifetime.

I'm suggesting that maybe in embedded in that, that that range of buildings that are designed for literally 500 to 1000 plus years and buildings that are literally designed maybe for 10 to 20 years, that we should explore the way this relationship is in between, of course, maybe they're 50 to 100 or 200. That may be in this relationship of a variety or our opportunities for cities to evolve in response to changing conditions. For example, the pandemic has presented needs, that our urban context does not presently or did not presently contemplate for outdoor space. This strategy may provide for a higher degree of flexibility for unanticipated shifts in climate change, pandemics of the future programmatic changes etc.

Alexandra: Another thing you brought up is human engagement. How do you, how do you see all this fitting into that?

Trey: I am deeply moved when someone grants us the privilege of a level of emotional engagement—that they're emotionally available. I think we have a responsibility as designers to think about that. When we grant someone access to who we are intellectually, emotionally, spiritually—it's a real privilege. If we're responsible with that, we develop a level of security that allows us to express, in a more deeper and more meaningful way, who we are. And that's what an important aspect of life is, ‘Who am I? What do I represent? What are my convictions, right?’

I think that buildings should possess a variety of spaces and should be designed to encourage meaningful human-to-human engagement, human-to-the-natural world engagement, and spaces for self-reflection.

I think that buildings should possess a variety of spaces and should be designed to encourage meaningful human-to-human engagement, human-to-the-natural world engagement, and even spaces for self-reflection. Because, if a place is about reflection and memory, and relationship to a space about action, those are complementary. They both reciprocally elevate life's experiences and the quality of life.

Alexandra: I can really identify with that. I feel very sensitive to my surroundings and spaces, and feel like having that supportive environment is super important for me, and I imagine it's probably a quite universal thing to feel.

Trey: Well, I think that that's one of the beauties that's come out of the pandemic, right? It has reminded us to think outside of ourselves, to think about our community, our neighbours, our family, and question how we contribute to others. As we all know, the beauty of that is how much it gives back to oneself, but I think architecture has a real role in that, and that we should think about that. I think the way architecture is expressed—its spatial quality, its engagement with the natural world, the environmental, uniqueness of place—is significant in either elevating or competing with human engagement.

Alexandra: Do you have any examples of that that you could share from your work, or just in general?

Alexandra: I can really identify with that. I feel very sensitive to my surroundings and spaces, and feel like having that supportive environment is super important for me, and I imagine it's probably a quite universal thing to feel.

Trey: Well, I think that that's one of the beauties that's come out of the pandemic, right? It has reminded us to think outside of ourselves, to think about our community, our neighbours, our family, and question how we contribute to others. As we all know, the beauty of that is how much it gives back to oneself, but I think architecture has a real role in that, and that we should think about that. I think the way architecture is expressed—its spatial quality, its engagement with the natural world, the environmental, uniqueness of place—is significant in either elevating or competing with human engagement.

Alexandra: Do you have any examples of that that you could share from your work, or just in general?

Trey: Yeah, well, for me, personally, I struggle with an overabundance of decor. I think, decoration, whether it's objects in a space or applied without any meaningful performative contributions, devalues the human presence. I think we should privilege life and privilege human presence in our spaces, and I question when someone feels the need, and this is for me personally, to fill a space with stuff.

I think, decoration, whether it's objects in a space or applied without any meaningful performative contributions, devalues the human presence.

Because I think, now more than ever it's important to not only listen, but to be truly present, and that seems to be more and more rare these days. ‘Is someone really present? Is their phone aside? Are they really listening in, or do they care?’ I think spatial definition, expression, materiality, mechanical systems, are the mechanical systems humming, are the lights buzzing? Is there a server running? Do you hear the computer? I think all those things are important to either competing with, or contributing to rich and meaningful human engagement.

Alexandra: It's interesting what you're saying, because lately I felt the same. I tend to do the same with things and decoration, but I've realised it's so much for my brain to process that I have all these things around me—and that's actually just taking away my energy more or less. I love what you're saying and that really puts some of your work even more into context for me. You have this one really beautiful chapel you designed in Louisiana. It's, and forgive me, I'm gonna say it wrong—St. Jean Vianney?

Trey: St. Jean Vianney. Yeah, one of our earliest projects.

Alexandra: Yeah, I was actually speaking with my intern at the moment, we were having a discussion about this, and he brought up some really interesting points, like how your work seems kind of devoid of excess ornamentation versus the more traditional Catholic "art of overwhelming", let's say. I think when you put it in those terms, it's really beautiful. I think it's interesting how you applied that to something so traditionally ornamental. Would you say this is like a theme throughout your work?

Trey: I think it is. I think it's fair to say we privilege life, we privilege human presence. And for us, there is some would say, a lack of colour, but I would argue that there's pigmentation—a variety of pigmentation in the pouring of cast-in-place concrete. If you choose to stop and look, there's almost a skin-like quality to the way concrete hydrates. To me, there's a beauty in that.

I like thinking about that, that someone's life's experiences and choices have affected their physical presence as a reflection of their journey, and how that plays in relationship to the canvas that the building is.

Furthermore, there's a beauty in that the human being, the occupants, bring the colour. I like thinking about that, that someone's life's experiences and choices have affected their physical presence as a reflection of their journey, and how that plays in relationship to the canvas that the building is.

Alexandra: Yes, I love this metaphor of a canvas. So then how would that apply to you? What sort of experiences and influences have affected your canvas?

Trey: Wow, that's an interesting question. I realised this recently, that I'm in search of places that are of quiet reflection. And it's not that I think of myself as this religious person, but I yearn for places and time—I am very much aware of the anxiety I feel in certain spaces and places. And I am very much aware of when I'm in spaces or places where my anxiety is reduced or eliminated. I'm very much aware of the way I think and the things I see, and more importantly, the things I feel about life and others when I'm in those places.

At the same time, I don't want to control life. I want to embed myself in experiences that have a high degree of unpredictability and that's found in the art that I collect. For example, I love the Raku family's tea bowls in Japan, or Shiro Tsujimura's tea bowls in Japan, because the artist there retrieves from the soil the clay—a soil of a high clay content, and he shapes it. But he has such a decency, such a humility, that he gifts the clay to the kiln, to the fire. He allows the kiln to take the shaped clay and elevate it to a far more beautiful place. He is very much aware, that although he may have been given talents, that the creation of beauty is far beyond his hands.

The beauty of is that unpredictability. You never know where the conversation is going to start and you're not even sure how it's going to evolve, but you know that it's going to be authentic and true, and serve as memory for the uniqueness of those collaborators.

I think that we should think of architecture in those terms. That's why I'm hopeful that the starchitect is gone and that we've become a profession with an elevated level of humility, and that we believe that maybe building is creating a framework to make some of the decisions, but not all of the decisions. And you might say, well how? Well, let's say we're going to build a poured-in-place concrete building.

Instead of the forms being so engineered, where they don't move, the formwork is attached through a series of hinges, pivots, rollers, and devices that allow the process of pumping concrete into it to have a conversation with the formwork—and the formwork moves in a way that results in a far more beautiful expression—a far more interesting internal space. Then, it hydrates unique to that form, because of its relationship to the sun and those atmospheric conditions. There's tremendous integrity, maturity, and wisdom in letting go, and trusting.

Alexandra: You spoke in another lecture about letting go of one's narcissism in the same context of the clay in the kiln, but I was just curious as to how that plays out in some of your projects?

Trey: That's a great question. As a young architect I wanted to control the engineers, I wanted, in some ways, to control the client. I wanted to control the conversation, the dialogue, on every level, and that's really ridiculous, and terribly immature—and actually disrespectful. So I think moving to a place where you're no longer threatened by the individual voices of all collaborators, but you find embedded in their life's experience in each contributor, that is important to the conversation.

The beauty of that, once again, is that unpredictability. You never know where the conversation is going to start and you're not even sure how it's going to evolve, but you know that it's going to be authentic and true, and serve as memory for the uniqueness of that group of collaborators. That's what I find interesting—is arriving at the office and not controlling things, but being granted the privilege of participating in conversations that may take us to a very different place.

You quickly realise that beauty, as we define it, should be about dignity, respect, empathy, and compassion, and physical beauty without a dignified process of creating, lacks beauty.

In recent years, it has taken us to a place where—are we architects? Yes. Do we love and are we passionate about architecture? Yes. But we realised at a certain point that more importantly, our role is to be humanitarians—and humanitarians that have chosen the profession of the material world in this natural world, and questioning what the role of the architect is, and believing truly, that we are in the early years of defining what an architect is, because I think, like all professions, there's just an inherent beauty in the way we think and see the world.

I think we need to move outside of these silos and really in the most radical way challenge not only what the architect does, or how the architect contributes, but the definition of beauty—because I think we're born into a world of defining beauty as the physical. You quickly realise that beauty, as we define it, should be about dignity, respect, empathy, and compassion, and physical beauty without a dignified process of creating, lacks beauty.

Beauty has to be far more, and it's my personal opinion that if there's one thing that can save the planet, it's how we redefine beauty. And beauty is the "we" right? Not the "me". It's thinking of others in our community and how we can contribute. Those are just a few ways of how we are challenging what the role of the architect is and how we think. Hopefully, embedded in those conversations, is potentially a far different way of thinking: about space, about relationships, about expression, and about building on this blue ball, right?

Alexandra: I really like what you're saying about this ‘starchitect’ and how you are approaching working with your team, you know, you get what you put in. I imagine this translates really well to this peace architecture that seems to be a pillar of your firm.

Trey: Yeah, it is. Yeah. And just to kind of finish up that thought of the starchitect—isn't it very disingenuous to suggest one person is this brilliant thought leader and responsible for this piece when so many people at every level in the office, consultants around the world—and as important, or maybe more importantly, the client and community are contributing to this?

So yeah, so as it relates to peace architecture—so to back up a few years. For some reason I've spent the past 25+ years travelling the state of Louisiana visiting historic buildings—the earliest ones constructed of bousillage—and I think it's because they are such beautiful examples of rootedness: Extracting timbers from the site, the cypress trees, the clay, horsehair and moss from the site, and then the cedar trees on the site, the cedar shakes for the roof. You feel that. You feel the materiality of place organised in a way that creates a level of conditioned space that feels so connected to place, both internal and external.

That's always been an inner struggle for me. How can, as a person that hopefully appreciates the physical, elevate that to a place of contributing, knowing the horrific atrocities that took place?

As I travelled the state—and there are many plantations in Louisiana—that in a physical way, devoid of the culture, and the atrocities that took place on the plantations, [they] are beautifully proportioned. They're beautifully rooted and created from clay, and kilns that make the bricks, and created these places where these oak allées take you through, on this axial condition, to this place of arrival and they feel very much connected to the landscape. That's always been an inner struggle for me. How can, as a person that hopefully appreciates the physical, elevate that to a place of contributing, knowing the horrific atrocities that took place?

The more you study these you realise that some of the early pink colours were blue, and that was indigo—and you think of indigo as a crop of oppression. So you start connecting all of these dots and you realise, that we probably practice architecture, the process of practising architecture, not only the physical expression, that is so rooted in those days of oppression, of a small group—controlling, manipulating, and shackling—so many. How can you not question if the birth of our country was not born out of that level of greed, of material possessions and wealth—whether it was wealth of land, of money, or of artefacts? How would we have evolved? Would our cities be different? Would our neighbourhoods be different? Would we think about the threshold of arrival and the sequence of progressing on to a site differently?

I have to believe that if we can find a way to go back and interrogate, truly with deep conviction and honesty—unearth, as archaeologists, the truth and commit to accepting the truth, telling the truth, for both the victim and the perpetrator—but to just with dignity, recognise this period in history and ask ourselves to go back, and hopefully almost begin again—not in an attempt to erase that history, but to acknowledge it.

Maybe, just maybe embedded in that truthful confrontation is a way of thinking of place and space that leaves each of us feeling elevated in a far more impactful way. So I'm interested in that. I believe that's not only the physical properties of place and architecture, but it's our role as architects to now think about crops that bring peace. We recently flew in Boubacar Fofana from Bamako, Mali, and he brought seeds of indigo, and we're planting them on a property we purchased.

How can you not question if the birth of our country was not born out of that level of greed, of material possessions and wealth—whether it was wealth of land, of money, or of artifacts? How would we have evolved? Would our cities be different? Would our neighbourhoods be different? Would we think about the threshold of arrival and the sequence of progressing on to a site differently?

He related that 6000 years ago, indigo was a crop that was used for medicinal purposes, and so it was in West Africa. So now in southern Louisiana, a crop that's thought of as oppressive, is now a crop for healing. You can rub an indigo leaf on you if you have a cut, and it contributes to the healing of the cut. You can put a few leaves in your mouth and they contribute to the healing of a toothache.

So for me, it's once again the soil providing conditions for—so we heal the soil, it provides us with plant life that can can heal the body and hopefully, the act of all races growing indigo, cutting indigo, using it for medicinal purposes, or maybe for dyeing purposes—beautiful Indigo dyed pieces are just magical. Maybe these are all ways of bringing communities together to deal with healing the community. For me, they once again go back to the soil and the importance of soil.

Alexandra: So what role then do you see architecture playing when it comes to, reparations and institutional reform, like in maybe more concrete ways?

Trey: Yeah. Well, I think first of all, we have to define reparations, and reparations come in many forms. Yes, most associated immediately, with money being transferred from the perpetrator to the victim. But, you know, the truth is marginalised people want, I think, first and foremost, acknowledgement of what took place and for that truth to be known, and that truth told, that story told, it documented in history, as opposed to another somewhat misleadingly, disingenuously recorded historical narrative. That does a disservice to all of us. It's so irresponsible to our kids and grandkids, so I think the truth must be established.

It's about stillness and quiet, and this almost inner universe that can serve as just an uninhabited vessel, that allows the element of mystery to embody this place—and for someone to enter and not find themselves entertained by decor, or artifacts that are about expressions of wealth, but more natural light.

I also think we need to make connections between the enslaved people of the past and modern day slavery—or what we refer to as the plantation to prison pipeline—and understanding all of these connections. I think it's fair to say that most of us, beginning with me, are just simply unaware of the things we do and say that are terribly insensitive. I have to believe that in confronting the truth and speaking the truth, we will think differently as architects. And so I care to know these things, I want to know these things. I want, at the end of my life, to know that I gave time and energy to exploring the truth, and participating in defining who I am and how I allocate my time, and my talents and contributions to the community. I can't imagine not confronting or fearing that, because if you don't know, I'm not sure you can be held accountable, but you can be held accountable for not wanting to know, and not seeking out the truth.

Alexandra: It seems like you do and I think authenticity is a word I would definitely use to describe you, Trey. I think that's a beautiful way of putting it. On the same note of authenticity, how do you apply that to your architecture to ensure a place is authentic to its locality, or community?

Trey: Yeah. So for us, we start with the watershed. I want to know what the watershed was, I want to know the soil type, I want to know the flora, I want to know the fauna, I want to know the topography, I want to know at the scale of soil, dirt, I want to know for example, if it's in a part of Louisiana—that's the low soils—that they are stable, sectionally speaking, in a vertical condition, least stable in a horizontal or a slope condition, because these particles of soil have a coating of clay on them. So when they're in a horizontal or a slope section, their surface area exposed to precipitation, they lose their frictional qualities. And so they experience degradation of the soils or exhaustion of the soils, or runoff.

There's tremendous beauty in the complexity of natural systems and their unpredictability, which is kind of like our urban cities.

And then I love thinking about how they are suspended in water and move on rivers, tributaries, distributaries. Then what are the tree species that grow out of that soil? So that's the most available species type. And how the forest in those places that soil has resulted in a variety, biodiversity. And how a building can have a dialogue with biodiversity where it is not singular. And that's where we struggle—how can it be authentic, but have that kind of complexity?

There's tremendous beauty in the complexity of natural systems and their unpredictability, which is kind of like our urban cities. That's the beauty of urban, there's so much diversity—which is real richness. Our search is not complete, in fact, it's early. I wish I would have come to this point many years back. I think embedded in that is a way of thinking that has the potential to result in a profession that contributes to our personal lives, our family's lives, and our communities in ways that touch us deep within that are unimaginable now. I believe we'll get there. My thinking is, if we know we're going to get there let's kind of accelerate this thing, and accept that it doesn't threaten us. It elevates us all. I just want to elevate it and expedite things as much as we can while I'm here.

Alexandra: Yeah, it has to be. I guess maybe the better question would have been like, how can it be preventive or proactive instead of reactive? I think you kind of got that. You made this other—and I think it was a metaphor about kind of sacred spaces, and I think you were describing, or maybe the person you were talking to was describing actually, like a football stadium as being the sacred space and this place where people connect, and to me that seems like that kind of space where all walks of life can come and maybe see each other in more of those human terms. I would love for you to talk more about that.

Trey: Yeah, that's a great example. So we're interviewing early in my career—we were selected for the LSU football stadium addition, which was an incredible client. So years later, we were interviewing for Auburn University's football stadium. The athletic director at the time was a wonderful man by the name of David Housel—and we're in this presentation room and about five minutes into the interview—I'm speaking—he stops me and he says, ‘Trey, I'm fascinated, by the way you think and the way you speak of architecture.’

He said, ‘I read once that you designed a church.’ I said, ‘Yes, sir.’ And he said, ‘Can you tell me what it's like designing a church for a community?’ I said, 'Well, you know, I mean first, the most important threshold is your private dwelling, when you choose to leave your private place, then you cross that threshold to the public realm, and you drive or walk to church and then there's the forecourt, and you arrive there and you meet others that are in the community, and then you cross that first threshold.' And I said, 'You arrive in the space.' And he goes, ‘Well, tell me more about that entry portal.’ This went on, Alex, for 20 or 30 minutes and I'm thinking my goodness, I mean, I love designing sacred spaces, but I wanted to really master plan this campus stadium.

And then he said, ‘When you design this church—this article spoke of equality, and bringing dignity to each member of the congregation, tell me about that.’ I said, 'Well, I don't think there should be varying degrees of participation. Every seat should be volumetrically in a singular space.' He said, ‘Well, speak to me about that.’ So we did. At that point, I'd given up on the potential selection as an architect for the stadium.

He said that arrival sequence entry and people-gathering of equality around the sacred table in a church, or the sacred field, is precisely the same. So your understanding of that commitment to community is very much a part of sporting events.

Then Alex, he walked to the window—this was 3540 minutes into it—and he pulled the curtain back and there was Jordan-Hare stadium, their campus stadium. And he said, ‘There's my cathedral.’ He said that arrival sequence entry and people-gathering of equality around the sacred table in a church, or the sacred field, is precisely the same. So your understanding of that commitment to community is very much a part of sporting events.

Obviously, I was taken aback by his brilliance to make such a beautiful connection between those two distinct building types. To kind of share more about that—then the conversation we had off-record, so to speak, was both of our intrigue with how someone can belong to the Republican Party, or someone can belong to the Democratic Party, and they can sit next to each other in the same colour rooting for the same team, and that which separates them in the most unpleasant way, is dissolved. They're so united against a common enemy—the other team.

All those experiences leave you thinking about how architecture can bring us together. I think that's where we've arrived in this conversation. Here, a collegiate stadium in the SEC takes people of all colours, and of race, ethnicity, cultural backgrounds, political persuasions, and if you're rooting for the same team, you are unified, and you embrace each other, against the other in the most profound, and at times horrific ways, but it speaks to the architecture right? On one level.

Alexandra: I would love to hear more about just how spirituality plays into your work in general—if you have more to share on that.

Trey: Yeah. Well, I think that—I mean, all our life experiences are one thread or another, right? Some beautifully contribute, in some ways, to who we are. Some challenge us to think about how that experience contributes, beautifully, to who I am and what I represent, and how I can contribute. I'll share something very personal. When I was 30, my older sister of 15 months, who was a beautiful, healthy, young woman, discovered she had cancer. She was engaged, and she married two weeks later, and she died two weeks after that. So within 29 days, at the age of 31, I lost a very close friend and sibling, and so the choice becomes, through all of that pain of loss—of what are my options? This can destroy me, this can result in a person that becomes introverted and fearful of life, or a person that chooses to celebrate the beauty of life.

We all have these threads of experiences through life that form a unique tapestry of who we are.

I think it's important to make those choices. We all have these threads of experiences through life that form a unique tapestry of who we are. I think embedded in those is the formation of who we are, and what we believe, and how we contribute, and how we contribute to others. It's not that I would ever seek to experience those days again, but I have to tell you at this point in my life, reflecting back, there is a tremendous beauty in that loss that some may find problematic to understand, but that is worthy of celebration, because it contributed in so many ways to who I am. I think it requires that I become a steward in many ways.

Stewardship is important and we don't talk a lot about it, but we have to be stewards of the land, a land ethic, stewards of the soil stewards of our community, stewards of our relationships. I think all those are born out of life's experiences and I try to give adequate time to thinking about all those experiences, and the importance of those, and how they contribute to human-engagement—relationships at all levels.

Alexandra: I'm so sorry to hear for your loss, and I definitely can understand how that would shape you. Very formative.

Trey: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

Alexandra: I think it's important to hold space for those sort of, like, conflicting emotions, let's say. And I think that's kind of the complexity of life that you were talking about. And I can resonate with that.

Trey: Absolutely, yeah. Yeah, I, as I said, find tremendous beauty embedded in these things. Once again, it's a reminder of the importance of celebrating life at all scales every day. And that, once again, reminds us of all of life embedded in healthy soils and the importance of being stewards of the soil, or stewards of the planet and our neighbourhoods. I'm confident that the trajectory of our planet and species will be far greater when we privilege all forms of life.

Alexandra: I 100% agree. Just so poetic. Everything you've said today and shared with us—I'm super grateful. So maybe, is there anything else, you would like to say that we didn't cover? That you feel like it's important to add to this conversation?

Trey: Yeah. I can't think of anything. Can you? Is there something else we should do? I think I've given you my all.

Alexandra: You've given me so much and I'm so grateful. So thank you so much I'm really excited about this conversation.

Trey: Well thank you, Alex. It's, it's been my privilege. And yeah, To be continued, right?

Alexandra: Yes, I like that—to be continued. And the pleasure is truly all mine. Thank you. Yeah.

Trey: Thank you, Alex. Take care. Have a good evening.

Alexandra: You as well. Bye.

Trey: Yeah. Bye-bye.

Trey Trahan, founder of Trahan Architects.

Trey’s emphasis on how architecture brings us together, not just with one another, but in communion with the natural world, is an idea worth contemplating. Through his work, he makes plain that architecture should foster equality and equal participation for those who enter the structures and the landscapes on which they are set. His role as an architect is not delimited by the boundaries of blueprints. Stewardship, he says, “of the land, of the soil, of our communities, of our relationships” is paramount if we are to heal the wounds inflicted by our past and current divisions.

For Trey, it is incumbent upon those within and without his profession to engage as stewards of their built and natural environments, for we must press forward together to really create an ‘architecture of healing’. Be sure to catch our published transcripts complete with images and visuals along with all other referenced works in this show’s description. Thanks for joining us today.

Design and the City is a reSITE production. reSITE is a global non-profit connecting people and ideas to improve the urban environment. This episode was directed and produced by myself, Alexandra Siebenthal and Nikkolas Zellers with the support of Martin Barry, Radka Ondrackova, as well as Nano Energies and the Czech Ministry of Culture. It was recorded in the reSITE office in Prague and edited by LittleBig Studio.

Listen to more from Design and the City

The Architecture of Healing with Michael Green + Natalie Telewiak

Michael Green and Natalie Telewiak love wood. These Vancouver-based architects champion the idea that Earth can, and should, grow our buildings--or grow the materials we use to build them on this episode of Design and the City. Photo courtesy of Ema Peter

Julia Gamolina on Breaking the Architect's Mold

A rising tide that raises all ships—Julia Gamolina’s efforts with Madame Architect in building a culture of community and collaboration give the diverse stories, perspectives, and the women they belong to a seat at the table. Listen to her episode on Design and the City. Photo courtesy of Sylvie Rosokoff

Winy Maas on Dipping Our Planet in Green

Design and the City is back with the first episode of our second season featuring co-founder of MVRDV, Winy Maas, in conversation with Martin Barry on greening our cities, his latest projects, and how constructive criticism leads to productivity. Listen now!

Michel Rojkind on the Social Responsibility of Design

reSITE's podcast, Design and the City, features Rojkind Arquitectos founder, Michel Rojkind in conversation with Martin Barry on how he uses design as a tool for social reconstruction.