Venice Architecture Biennale U.S. Pavilion: American Framing with Paul Andersen + Paul Preissner

reSITE is back with a special two-part Design and the City episode covering the long-awaited Venice Architecture Biennale to explore the question “How will we live together?” Part-one covers the U.S, Pavilion curators, Paul Andersen and Paul Preissner as they reexamine humble softwoods and their place as the literal bones for American homes in their exhibition entitled “American Framing”.

The postponed 17th Venice Architecture Biennale asked its 112 participants to consider the question, “How will we live together?”. A question originally posed in 2019 by curator and architect, Hashim Sarkis far before our collective 2020 experience. Sarkis originally asked participants “to imagine spaces in which we can generously live together” Answers from 46 countries materialized into the exhibition of 2021. After a year spent living apart, the theme is both hauntingly fitting and reifies our disconnection.

Listen to part one of our special episodes on the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale on Design and the City now:

It has signalled something, a community eager to reconnect and a deeper understanding of just how interwoven we are with our spaces spanning the full spectrum of human existence. The exhibition explores that spectrum across five scales: Among Diverse Beings, As New Households, As Emerging Communities, Across Borders, and, As One Planet.

reSITE got the opportunity to attend the preview to speak with some of this year’s contributors on site. In this episode we’ll hear from the U.S. pavilion curators, Paul Anderson and Paul Preissner; exhibitors Lukas Feireiss and Leopold Banchini; curator from Luxembourg, Sara Noel Costa De Araujo; and finally exhibitors for the Nordic Pavilion, Siv Helene Stangeland and Reinhard Kropf–all whose work shares a common thread–wood.

These wood-based installations make cases for their egalitarian and democratic nature. They offer a particular simplicity, humility, flexibility and familiarity coupled with considerate retrospectives, to not only answer the pressing question, “How will we live together?” but “how will we thrive together?”

How will we thrive together?

U.S. Pavilion, American Framing: Paul Andersen + Paul Preissner

Practical, banal and cheap. Descriptors are often used when speaking about wood as a building material. Architects Paul Andersen and Paul Preissner, curators of the U.S. Pavilion, invite us to reexamine humble softwoods and their place as the literal bones for American homes in their exhibition entitled “American Framing”.

Relatively uncommon throughout the world, Paul and Paul are quick to note that over 90% of the houses constructed in the United States are wood framed. While there is undoubtedly a sameness and a certain banality to this style, the curators stress its accessibility. It is with this one material that a diversity of structures are made and yet, it is architecture that is widely overlooked. They posit that it is a representation of democratic values, egalitarianism and pragmatism, as softwood is cheap and offers opportunities for structural improvisation.

The installation itself is unmissable within the Giardini. The curators attached a 3-story tall structure to the outside of the U.S. pavilion, providing a striking juxtaposition given the humble nature of wood framing and the monumental statement its making. I spoke with both of them just outside the Giardini in Venice during the opening weekend.

Alexandra Siebenthal, reSITE: Would you mind introducing yourselves?

Paul Andersen, Curator of the U.S. Pavilion, American Framing: My name is Paul Andersen and I'm one of the curators, I have an office in Denver and I teach at UIC University of Illinois Chicago and where a lot of the people, including Paul Preissner, are also working and teaching, a lot of the people that work, we work together on the pavilion, so it's a pleasure.

Paul Preissner, Curator of the U.S. Pavilion, American Framing:: Hi, I'm Paul Preissner. I'm also a faculty at the University of Illinois Chicago and have my own architecture practice there as well.

The materials that we choose are common, ordinary materials—nothing super technologically advanced or exotic—and more things that most people probably recognize and can relate to.

Alexandra: And how did the both of you kind of connect and start working together? Because I've seen you've collaborated on other projects, if that's correct?

Preissner: Yeah, I guess we've worked together since 2014 or so–13, 14–five, or six or so years ago. We met at the university, teaching together. So I started there in 2007, and Paul started a little bit later, and we met at the school. So we've started I guess, you know, we kind of maintain our own independent practices and have come together to work on installation projects for art exhibitions, or architecture exhibitions.

Andersen: Yeah, I mean, I think a lot of the things that we've tried to set up here in Venice are an extension of that work. In the end, like all of the projects that we've done together for exhibitions have been, like full scale constructions of some kind. Sometimes they're inside, sometimes they're outside, using different materials. But generally, the materials that we choose are common ordinary materials–nothing like that super technologically advanced or exotic–and more things that most people probably recognise and can relate to, in some way, but then trying to set it up or design a way of using them that that isn't quite so familiar, and maybe allows them to see those materials and maybe the built world a little bit differently.

Alexandra: That's fantastic. Okay, so maybe tell us a little bit about this idea of framing, kind of as a starting point. You mentioned it's for, you know, more for research and discourse and less than looking at what's been done in the past.

Preissner: I think it came from looking at the overall history, not a kind of specific one, but American framing, as is the title of the exhibition. It's more of a kind of a topic show or a subject show, looking at American architecture, not American architects.

We'll live together in wood framing because that's what we do. But we'll also live together in a more wily, domestic type that kind of explores new forms of creativity based on normalcy, as opposed to the exotic.

And the title, in a way, kind of works both literally in the sense that it is the framing that happens within America and accounts for over 90% of domestic construction in the US. But it's also kind of metaphorical or speaks to a particular cultural ethos of America–one that is a little bit more bored with tradition and kind of prioritises, or privileges, expediency and kind of utility or usage over more delicate or slower forms of craft and precision.

Alexandra: What does the question of how will we live together mean to you as designers, as curators?

Preissner: Yeah, it's interesting, because of the artistic direction–because of the schedule of award of the grant to produce the US pavilion–the artistic direction came after we had already developed the project, submitted it, and found out. So in that sense, it wasn't a conscious and direct response to the question asked by Hashim, "how do we live together?" But, but nonetheless, I think it has kind of, you know, the quick answer: “we'll live together in wood framing because that's what we do”. But we'll also live together in kind of a more wily, domestic type that kind of explores new forms of creativity based in normalcy, as opposed to the exotic.

Alexandra: I appreciate that. You also mentioned that the style of framing is rooted in equality. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Preissner: Yeah, so it developed in the early 19th century, and it came kind of from the need for an enormous amount of housing as the American population was expanding. A lot of immigrants within the Midwest–where it started–were from Scandinavia, Germany, and came from those traditions of heavy timber framing, stone work–much slower, more elaborate forms of construction. But the population just didn't have access to the kind of educated skill, the tools necessary to do that. And also, the region just wasn't populated with the same types of wood. So the Midwest–Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois–had a much cheaper kind of disregarded form of woods, off wood. The trees grow fast, and as such, they splinter, they're not as strong. So it wasn't used for the way things were built with elaborate joints, carved joinery and stuff.

By using a lot of really small, cheap pieces of wood and nails, nailing boards into boards, started to produce a kind of architecture that had its own grammar, its own informality.

So it kind of developed as a really quick, easy way to use wood that you wouldn't like by instead of just using less things to produce the, you know, the structural load of the house, they just use lots of them. So instead of four columns to hold up a house, you had 80, or such, and they were all these small studs. And by using a lot of really small, cheap pieces of wood and nails, just nailing boards into boards, instead of trying to slot them in it, started to produce a kind of architecture that had its own grammar, its own informality, but still produced to kind of domesticity.

Andersen: Yeah, like for all those reasons, because it was easy to work with and because the wood was plentiful and inexpensive, it was something that everybody could use. And that is still true. So, today, over 90% of homes in the US, or, you know, like Paul mentioned, are built with wood framing, but it's all the same framing. So, no matter how much money you have, you can't buy a better two-by-four than the one that your neighbour has. So there is a kind of equality, I think, in that that is, you know, interesting, and maybe works on some ideological levels, but also for design, opens up a lot of possibilities that, you know, maybe other construction systems don't allow for.

The improvisation, the quirkiness, the ease of experimentation, and change on the fly, are all things that are part of that ethos of a kind of egalitarian system.

I think that the improvisation, the quirkiness, the ease of experimentation, and change on the fly, are all things that are part of that ethos of a kind of egalitarian system that's cheap and quick and easy.

Alexandra: And you already touched on this maybe a little bit, but why do you feel it's so uniquely American?

Andersen: I mean, I think there is the very direct, literal answer to that, which is that we build primarily out of wood framing, whereas, there's quite a bit of it in Canada also. But outside of North America, there are examples of it, but at least when it comes to stick-built, lightweight, soft wood framing, there's not a whole lot of it around the world. It tends to be more of an exception or an anomaly in most places than the standard way to work.

So, it is very straightforwardly an American way to build that, for whatever reason, is not, for lots of reasons, the way to build in other places. And I think maybe both that kind of the egalitarian sense of "it's all sort of the same stuff for everyone, no matter what they're building, no matter what type of building, no matter how expensive", that seems to be quite American. Then there's the kind of anti-tradition part of it, which comes in, in a lot of ways, in through artistic practices. But also, we tend to think of architecture as being stable and permanent and heavy. Wood framing is lightweight, kind of flimsy.

Out of that has come some very American cultural practices that have embraced that fluidity.

There's always been sceptics who questioned whether or not it's a good system for building in because is it durable, and is it gonna last? But out of that has come, I think, some very American cultural practices that have embraced that fluidity.

For example, the idea that you would just move a wall on a house, or change the location of a window, or at a skylight, or something like that, it's really really easy with wood framing. It's not so easy if you have some of that building built in concrete or steel or masonry. So I think that that sort of sense that things are not permanent, that they're shifting, that they can always be new, they can always be different, and always be changed, seems to jive with American life, too.

Alexandra: Why do you feel the style is often overlooked? One thing I really liked is that you seem to be really interested in maybe the more plain and simple and humble practices of architecture. But, when you walk up to the pavilion there is quite a statement, a structure that you installed. I think that's quite powerful, just the commentary and the humbleness of it, but with like, very arresting structure.

Preissner: I mean, I think it's, it's overlooked in the sense that everybody knows about it, over 90% of the homes are built by it. So it's overlooked in a kind of intellectual sense, or overlooked as a way of producing architecture that's open for new forms of creativity or expression. In a sense, it's utterly normal, and therefore gets disregarded. It's something worth spending time on, either intellectually or creatively, in a sense.

It's overlooked in [an] intellectual sense, as a way of producing architecture that's open for new forms of creativity or expression.

I think Paul and I have always–one thing we've done when we've worked together is always try and work with anonymous histories or anonymous materials–things that are vaguely familiar that you grew up with, and you see it everywhere and you see it anywhere–but to try and produce a kind of new form of profundity with those methods, in a sense.

So, we think it is profound, and it's consequential, and it's big, but it's also done in a way that is a little bit disarming because it's familiar and approachable and you understand it, but it's also utterly new simultaneously. That kind of conflict of emotions or responses or experiences, we think, is a little bit more special and consequential than to produce something immediately exotic that you're then trying to normalise. We're doing the inverse, which is to take the normal and kind of make it weird.

Alexandra: Building on that a little bit, I read your interview with Kate Wagner–Kate actually spoke at one of our conferences, or last conference. Really incredible, I really appreciate her work. It was the interview for ArchDaily, and you discussed with her some of the urban/suburban divide. A lot of what people find distasteful about the suburbs, you find fascinating.

Preissner: Yeah, of course. I mean, I think that the suburbs get demeaned within a higher level of architectural discourse or something–it's considered tasteless, tacky, in the interests of people with no idea of what proper architecture is. I think what has always been, what's interesting to Paul and I about the suburbs is that within that tackiness, or within that tastelessness, also, is an enormous amount of weirdness and kind of creative choices that are made that aren't orthodox choices, in a sense.

What's interesting to [us] about the suburbs is that within that tackiness, or tastelessness, is an enormous amount of weirdness and creative choices that are made that aren't orthodox choices.

And so I think that type of unorthodox nature of formal expression or organising a plan–the house plans–for suburban developments are really weird in ways too, because a lot of them are just willful, or sometimes overly excessive, or just organised in ways that you wouldn't do it with other forms of construction. You can do it because it's wood framing. So I think we kind of like that out of fashionable weirdness that exists, and feel that that's a kind of form of creative expression too, that is enormously valid and actually produces something much more consequential, in a way.

Andersen: Yeah, I totally agree with that. I think there are a lot of reasons why the suburbs are worth taking a look at or spending a little bit of time on. For sure, one of the main main reasons is what Paul said, that there's a kind of low or pop culture development of ideas and forms and organisations there that can be really fascinating and can be actually very rich if you are patient and look close enough and don't dismiss things so quickly.

I was just reminded of a conversation from a couple of years ago that I hadn't thought of in a long time with a guy named Bob Brueggemann, who was an amazing historian also based at UIC, and very much a provocative person who goes against the grain in some really interesting ways a lot of times. We were having a casual conversation one day, and he happened to mention that a lot of the architecture that he was seeing, that's avant garde–or was at the time–for example, some of the Libeskind buildings, were basically the same as McMansions. They were both aggregations of self-similar parts, it's just that the parts were a little bit different, they were a little bit different form. But they were all kind of the same parts just repeated and globbed together in some way.

That correspondence was amazing, I never thought of that. I thought of those worlds as being so far apart, and people really would at that time take a stand for the kind of architecture that Libeskind was doing, but not ever definitely for the McMansion. It made me realise that, first of all, all of these preferences are cultivated and cultured, and biased, but also you can't dismiss the suburbs as being uniform and always one thing and always abhorrent, and that, actually, you should look closer, because they are different. Houses are different from different eras in different places. Absolutely, there's some very interesting things there that go against the unwritten rules of contemporary and traditional architectural design. So, yeah, it's good to take a closer look.

Alexandra: So, what will become of the structure once you dismantle it? Do you have plans to sort of reuse the materials in some way, or readapt?

Preissner: So we don't have anything definitive as to what will happen. We're in conversations with a couple of different people right now who want to absorb the structure and repurpose it either in the way it is now or in some kind of reassembly. So it won't just be burned, in a sense, or just thrown into the lagoon, but we'll find a home somewhere else in some kind of configuration.

Alexandra: That's great. Yeah, it seems to be kind of a theme, and a lot of the installations that we've seen are actually using this timber and these timber installations. Have you seen some of the other pavilions?

Andersen: There's a lot of correspondence for sure, there's a lot of overlap. It's funny because our immediate neighbours, spatially, on one side, we have Norway's contribution. Their work is also with softwood, and more like a configurable interior, and how that relates to community life, and maybe can open up some different ways for people to live together and form their environments together. Then, just kind of across diagonally in front of us is the Finnish pavilion, and they are looking at a prefabricated wood housing system from the 1940s and 50s.

How did they customize them? [The pavilion examines] the differentiation of these houses that were all identical to start with, and how that became a project of the people who lived in them.

Also, [the installation used] soft wood, also looking at what part of that was designed, what part of it was then later changed by the people who lived in the houses. How did they customise them? [The pavilion examines] the differentiation of these houses that were all identical to start with, and how that became a project of the people who lived in them. It's very interesting–the issues of authorship and materials. We've talked with them and it's been a good exchange of ideas for sure.

Alexandra: One thing we've explored in some of our other podcasts, or just interviews, is just the sustainability aspect of it. But one thing why I asked about the reuse that I find very beautiful about it–and maybe this is also something that's uniquely American– is that just as wood ages, it really becomes more valuable. You see these places, especially in the Midwest, where they salvage barns and people come and buy that wood because it has this textural quality. I don't know if you have anything to add to that, but that's one part I really love about particular wood structures.

Preissner: I think there is the kind of patina of wood that people appreciate, especially with the kind of old growth, forests, woods, oaks and chestnuts, and things you get that are a little bit better. What's interesting, I guess, about the soft woods–like spruces and Douglas firs that are used in the stick construction or American framing–is that the trees grow really quickly. So, you can kind of sustainably manage forests.

It's not as deleterious to the environment as using, say, hardwoods, which take half a century to grow. [Softwoods] can actually keep up with the kind of domestic need in ways that other materials can't.

While you're producing the material for the houses, you're also growing trees, which has a kind of additional benefit. It's not as deleterious to the environment as using, say, hardwoods, which take half a century to grow and take much longer. So, it can actually keep up with the kind of domestic need in ways that other materials can't.

Alexandra: Is there anything you hope to influence with your installation?

Andersen: The influence might be... I don't know if I'd put it in those terms. I don't think we had ambitions to influence anybody in a particular way. But we definitely thought of it as a project of opening up a topic, trying to try to look at it a little bit more closely and give a thoughtful presentation of the subject matter to other architects and to people in general, whoever is the audience of the biennale, whoever comes, any visitor.

For us, I guess we're trying to make a case for the field to take a closer look. We think that there's some interesting work that could come out of it, and hopefully it will. But, if and how that happens is out of our hands now. We've put it out there and hopefully some people pick it up and do something with it. It's provocative for some people in terms of their ideas and questions about how to work.

Preissner: Yeah, for me, I guess maybe influence isn't the right word, but [rather] alert people or kind of make visible and understanding. I think what we wanted with the installation in the front is we kind of think of it more as an addition to the existing US pavilion from 1930. So, it kind of literally completes it in the sense that it produces a formalised courtyard space, a kind of protected courtyard space, a private social space on the interior.

Then metaphorically, it also kind of joins the early 20th century cultural aspirations of the United States, made visible through this kind of adoption of European Palladianism in the way of the structure, and then completing it with the most ubiquitous form of domestic structure. And so it works for us more like a completion to the building and a way to kind of alert you to what's at stake and the consequences of the exhibition, to see something that is both kind of monumental and anti-monumental simultaneously, and that there's nothing special about it, but it's like nothing you've ever seen.

It works [as] a completion to the building and a way to alert you to what's at stake and the consequences of the exhibition—to see something that is both kinds of monumental and anti-monumental—that there's nothing special about it, but it's like nothing you've ever seen.

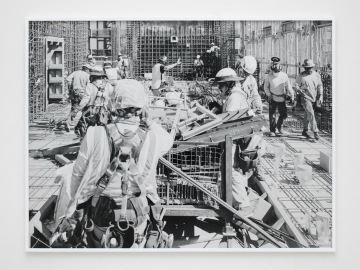

And that in a way conditions you to what's at stake and allows you to then explore the interior, the galleries, and the exhibition, where we start to look at the kind of traditions of the history; the way it was packaged as either kit homes, the kind of details of the site, the kind of messiness of the very temporal construction process that only takes a number of weeks to go from no framed house to a fully framed house; to explore the kind of natures of labour and the kind of social aspects of labour, the precarious parts of undocumented workers and day labourers, to the more professionalised labour that you have with union carpentry; and then to kind of get into the myths and the origin stories of trees and texture, seeing the trees for the forest instead of the forest for the trees.

We have a set of models that kind of track the history and explore different types of housing, from the kind of euphoric and utopic conditions of countercultural developments in Colorado, to the more brutal, oppressive instances of the architecture being used for the more unkind reasons, like US military outposts in the Midwest, to kind of really explore the periphery and the margins as a way of getting a deeper understanding of what's at stake with architecture in general. So for us, I think the show was always meant to be about architecture, not architects. In a way, that also might be how we respond to how we live together, because it's about a kind of social project that architecture participates in.

Alexandra: What do you feel will define our generation architecturally?

Paul: I mean, that's hard to say. I know we're currently–I mean, this isn't new, this has been [around] for a while, but it seems to have stuck pretty hard, I think. There's a strong backlash against signature. I think it's clear that no matter what your project is, what your ambitions are, very few people are invested in signature form or signature, like a signature sensibility in their works. Maybe that's what it will be in the end. But, yeah, at the moment, it's pretty hard to say.

Preissner: I think Paul's right in the sense that there's one thread that's a kind of backlash against more exotic works. But, it seems like we're also just kind of caught in a moment where nobody knows what is good, or nobody knows what to do. There's a lot of competing interests and competing inquiries into both what's possible and what we should do. It's difficult.

I think architecture, unlike art, and unlike other forms of creative practices, is a much more compromised field. Even cheap architecture isn't really cheap in absolute terms. I think people struggle with what architecture is supposed to mean and do, and who it's supposed to be for and who it's supposed to represent, and how it's used as symbols of power or oppression, or how it's used as things that are inviting to develop new social spaces or conceptual spaces for people.

I think people struggle with what architecture is supposed to mean and do, and who it's supposed to be for and who it's supposed to represent, and how it's used as symbols of power or oppression.

I don't know what this generation or the next one will do for architecture, I don't think it'll be defined in terms of a formal style. But, I don't think it will be anti-formal in that sense either, where it just dematerialised into things that aren't architecture, that are actually more policy driven or something like that. So right now is, I think, really interesting for me because it feels like we're trying to figure these things out and wrestle with our own histories, and what the future could be, and how architecture can produce and condition that and be conditioned by it.

The follow up to this episode will feature a special interview between the curator of the Venice Biennale, architect Hashim Sarkis in conversation with reSITE’s own former curator, Greg Lindsay. We will then continue to explore this year's question, “how will we live together”, but through the lens of accessibility with the curators of the Austrian and British pavilions.

We have loved getting to create this podcast, and we hope you’ve been enjoying it just as much. Reaching a new audience, on a new platform with the same mission—elevating people and ideas to improve the urban environment—in the middle of a pandemic has been what we feel to be an important action. Also important to us is that these ideas remain accessible and free.

As a nonprofit, we are only able to produce this podcast thanks to the generous support of the City of Prague, the Czech Ministry of Culture, corporate sponsors, private philanthropists, and our network of passionate architecture and city lovers, like you. If you would like to support us as a patron, sponsor or strategic partner, please get in touch with us at podcast@resite.org. Your support allows us to continue sharing ideas to inspire more livable, lovable cities.

This episode was directed and produced by myself, Alexandra Siebenthal and Radka Ondrackova and with support from Martin Barry, Nikkolas Zellers, Weronika Koleda, and Anna Stava, as well as Nano Energies and the Czech Ministry of Culture. It was edited by LittleBig Studio.

More Venice Biennale curators featured in this episode:

Venice Architecture Biennale: How Will We Live Together? [Part 1]

reSITE is back with a special two-part Design and the City episode covering the long-awaited Venice Architecture Biennale to explore the question “How will we live together?” Part-one covers the U.S, Nordic and Luxembourg Pavilion curators for their use of timber and wood construction to answer this years pressing question.

Venice Architecture Biennale Luxembourg Pavilion: Homes for Luxembourg with Sara Noel Costa De Araujo

reSITE is back with a special two-part Design and the City episode covering the long-awaited Venice Architecture Biennale to explore the question “How will we live together?” Sara Noel Costa De Araujo designed Homes for Luxembourg, to explore modular, reversible wood-based designs ideal for a country whose land prices render housing unaffordable and out of reach for much of the population.

Venice Architecture Biennale Nordic Pavilion: What We Share with Siv Helene Stangeland + Reinhard Kropf

reSITE is back with a special two-part Design and the City episode covering the long-awaited Venice Architecture Biennale to explore the question “How will we live together?” We spoke with exhibitors of the Nordic Pavilion, Siv Helene Stangeland and Reinhard Kropf, entitled What We Share about the inspiration behind their co-living experiment in Stavanger, Norway, which they not only designed, but also occupy, along with 65 other tenants.

Venice Architecture Biennale: There Are Walls That Want to Prowl, Lukas Feireiss + Leopold Banchini

reSITE is back with a special two-part Design and the City episode covering the long-awaited Venice Architecture Biennale to explore the question “How will we live together?” with curators Lukas Feireiss and Leopold Banchini to discuss their definitions of shelter, application of wood structures, degrowth models and retrospectives to rethink how we will live together.

More from Design and the City

Vishaan Chakrabarti on Creating an Architecture of Belonging

Listen to Vishaan Chakrabarti on the future of mobility, designing streets as public spaces, and creating an architecture of belonging on this episode of Design and the City

Why is Birth a Design Problem with Kim Holden

Can rethinking and redesigning the ways birth is approached shift the outcomes of labor and birth experiences? Can it be instrumental in improving our qualities of life--in our environments, in cities, and beyond? Architect and founder of Doula x Design Kim Holden join Design and the City to explore how she sees birth as a design problem. Photo by Kate Carlton Photography

Tim Gill on Building Child-Friendly Cities

A city that is good for children, is good for everyone--and idea we explore with Tim Gill, author of Urban Playground: How Child-Friendly Planning and Design Can Save Cities, on this episode of Design and the City. Photo by Els Lena Eeckhout.

Beirut: After the Dust Settles with Christele Harrouk + Salim Rouhana

We are taking on the devastating Beirut explosion with two of the city's natives. They will share their perspectives on what rebuilding the city of Beirut could look like after such an unbelievable event. Photo courtesy of Rami Rizk.