Vishaan Chakrabarti on Creating an Architecture of Belonging

Listen to Vishaan Chakrabarti on the future of mobility, designing streets as public spaces, and creating an architecture of belonging on this episode of Design and the City

Listen to Vishaan Chakrabarti on Design and the City:

Vishaan Chakrabarti is the founder and creative director of Practice for Architecture and Urbanism (PAU) and recently accepted the position as the Dean of the William W. Wurster College of Environmental Design at the University of California, Berkeley.

From 2012 to 2015, Vishaan was a principal at SHoP Architects. Pior to that, he served under Mayor Bloomberg as the director of City Planning in post-9/11 New York.In this appointed position, he collaborated on several development projects that have evolved the face of New York’s public spaces. The now-realized regenerative effort of the High Line, the rebuilding of the East River Waterfront, and the reincorporation of the street grid at the World Trade Center site are among them.

Vishaan has made some thoughtful arguments against banal, processed urban design being detrimental to our ability to thrive as human beings. In his TED Talk, he draws on imagery from the globe's most iconic cities, contrasting them with the cold anonymity of many modern ones. That effort can be seen in PAU’s versatile, mixed-use village in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia which interprets the region's nomadic heritage through innovative, flexible design that can be repeated and adapted to local communities, climates and construction methods, elsewhere.

His book, however, "A Country of Cities: A Manifesto for an Urban America" is what embodies the heart of his work. He makes the case that well-designed cities are the key to solving the United States' great national challenges, by reimagining them to hold more inclusive, prosperous, and egalitarian societies.

reSITE’s founder, Martin Barry, joins Vishaan Chakrabarti in a conversation about the future of our cities, addressing some of the inevitable evolutions, specifically around mobility, that will come with the rising populations in urban environments.

Martin Barry, reSITE: Okay, hi, everybody. So, we've got a lot of questions for Vishaan, and Vishaan, thanks for joining us.

Vishaan Chakrabarti, PAU + College of Environmental Design, UC Berkeley: Nice to be here. Thanks.

Martin: Sure. So we're gonna weave in between a bunch of things because Vishaan’s interests and his career [fields] are diverse. And maybe I'll just start, really briefly and simply, by asking you Vishaan, how are you doing? What’s up?

Vishaan: I think I'm doing as well as can be expected. I mean, I think we're all struggling through this pandemic. I'm one of the lucky ones. I mean, I have a job and I have, you know, my family nearby; I really worry about all the people who have extraordinary amounts of stress and live in small apartments with small families and are losing work. I bartended my way through a lot of my grad school education, and I kind of know what restaurant life is like. And I think it's really hard for a lot of people right now. So I'm one of the lucky ones, thanks.

Martin: That’s good to hear. I think [for] those of us who are either running our own businesses or have jobs, this pandemic is tough. We have a business, which is kind of at the forefront of the crisis, in food and beverage hospitality, [it’s] one of our entities, and we're definitely feeling the pain there. It's not so easy. But, you started in Berkeley last summer in July, is that right? So you had, kind of, a couple semesters under your belt before we dealt with COVID. Maybe you can just start telling us a little bit about what that's like; you made a big move from New York to California. You have a relatively new practice, and now you're dealing with a ton of disruption— with COVID, there have been racial riots, there have been historic wildfires in California, and now you're sort of starting a new life; it must be challenging. So, maybe tell us a little bit [about] what's happening at Berkeley these days.

Vishaan: Yeah, I appreciate your asking. I mean, it's been a hell of a year; 2020 is going to really be legendary, I think. Yeah, you know, I've been teaching at Columbia for about 10 years and lived in New York for about 27, and started my practice about five years ago. Actually, we just celebrated our five year anniversary, and moved here this summer, with my family, to the Bay Area.

[Almost] immediately, you know—obviously, the pandemic was well underway—Berkeley went to remote instruction last spring, we’re [doing] remote instruction now, and then immediately got immersed in what I would call Johnny Cash’s “ring of fire,” in terms of the Bay Area. Where we are in Berkeley, is kind of the doughnut hole of a bunch of fires that have sprouted [up] all around us. We were actually evacuated from a fire a few weeks ago up in Napa. And we're under the Red Flag Warning, as we speak, meaning the Berkeley-Oakland Hills are under severe fire watch, through the course of this weekend.

This idea that it wasn't just about architecture and planning and landscape, but how those disciplines could, in an interdisciplinary way, attack issues of climate change and social injustice.

And so, you know, I try to think about this stuff, not in terms of how it impacts me personally, but more, you know, “What does this mean for the world? What does it mean for our discipline? How did we get here? How do we get out of this mess we've created?” And [I think] how can, you know, I run a college called the College of Environmental Design. It was named—that college—very purposefully, in 1959 by William Werster and Catherine Bauer Wurster, as this idea that it wasn't just about architecture and planning and landscape, but how those disciplines could, in an interdisciplinary way, attack issues of climate change and social injustice.

That was in 1959; they were thinking about that, which is really extraordinary. So, I really try to look at everything that we've gone through, through the lens of, “how are the professions I represent in the world relevant to the crises we have before us, in terms of both climate change and racial reckoning?” I think they are, I think the disciplines are very relevant to those issues, as we kind of rethink human habitation, coming out of this mess. So that's what I'm very focused on, actually.

Another prominent discussion that has taken place this year, even more so in the wake of the first COVID lockdown, was the return of streets to pedestrian use. New York was one of the first cities to designate streets as temporary public space, to help residents better cope with social distancing. Streets turned into recreational spaces, restaurants spilled out onto streets as “streeteries,” and the idea of streets as public spaces, meant for social interactions, seemed to enter our collective consciousness.

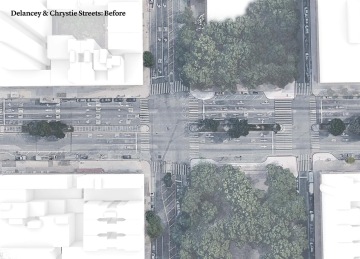

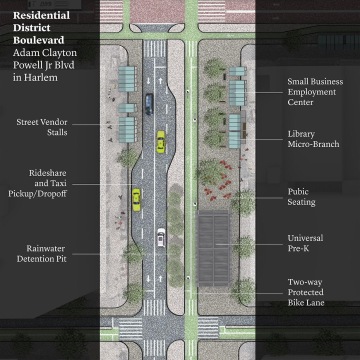

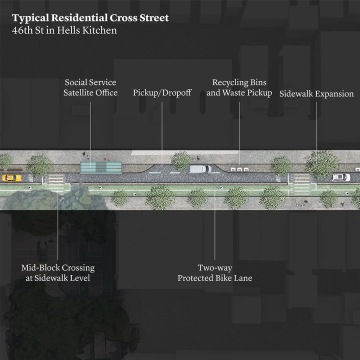

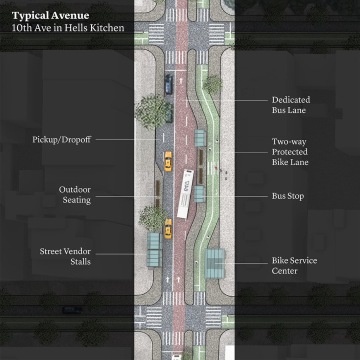

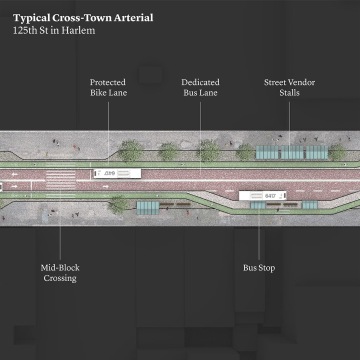

A recently published opinion piece titled “I’ve Seen a Future Without Cars, and It’s Amazing” written by Farhad Manjoo, featured PAU’s proposed visualizations of what a car-free Manhattan could look like, making that idea materialize in a way that was more tangible than before.

Vishaan sees car-dependency as incredibly undemocratic and deeply inequitable. Aside from the number of deaths that lay at the hands of automobile accidents, and how truly detrimental to the environment they are, his plan to reimagine the city without them tackles one of the lesser-discussed implications—their poor use of physical space per person is a profound waste of land—especially in populated cities.

Martin and Vishaan dive into how our car-centric culture influences our cities’ design, the realities of driverless cars as a solution, and what the inevitable evolutions of mobility might look like.

Martin: Yeah, these are big questions for academia and practice. I think [for] those of us—I used to be in practice—and [for] those that are still in practice, I think there are a lot of lessons to be learned in this time, and probably huge opportunities. I think one of them [which] you've commented on recently, is the carless city, and what the future of the carless city might look like. This is one of the things that we started thinking about earlier as urbanists. In this pandemic, particularly in cities like New York, in Manhattan, where I'm from, we saw streets open up for the first time in our lives. You could almost sense the fresh air; even though I haven't been back in New York since February, I could [sense] the space in the air. The feeling was kind of palpable that, “Wow, this is like a new city.”

Tell us a little bit about this. Your comments in the [New York Times] article with Farhad Manjoo recently, were kind of stirring. I think a lot of people were [thinking]. They're provocative; they’re interesting for a lot of us, [who have] thought about how to change New York City’s streets for a long time. Certainly, as you did, underneath Mayor Bloomberg. So what's this like? Is this going to be a permanent change? What needs to happen for cities like New York to transition to more carless cities, and what are the impacts? I mean, obviously, the climate change impacts are obvious, but maybe there are others that we're not thinking about yet?

Vishaan: Well, yeah, I mean, first of all, I think the proposal—and thank you for looking at it—I think Farhad did an amazing, amazing job with it, and I was so grateful for that. I think what we proposed is both radical and inevitable. I think, over the course of the next decade or two, you're going to start seeing major cities—and people really need to hear those words, “major cities.” I'm not talking about everywhere, I understand. There are lots of places that need cars to get around, but I think within the heart of major cities—we're going to see them eliminating private cars.

I think what we proposed is both radical and inevitable. There are lots of places that need cars to get around, but I think within the heart of major cities—we're going to see them eliminating private cars.

The reason I think that's inevitable is, well, climate is obviously one of the reasons but also, you know, we are steadily moving towards a world of 10 billion people by the year 2100. [We are] going to probably reach a steady state of about 10 billion people, and by 2050, 70% of the world's population will live in cities. And so our existing cities, because I don't think this is just about building all these new cities from scratch, will see some of that. But most of it is about how our existing cities take on this influx of population, and we just don't have the room for people to move around in these individual tin cans.

I don't care whether they're, you know, electric cars or autonomous cars. As far as I'm concerned, that's all a distraction. The real issue is a spatial issue, which is why we, as designers, need to get in the mix in this conversation. It's just extraordinarily inefficient, for one human being to be travelling around in this gargantuan, couple of tonne machine through the streets of our cities. And what we really tried to illustrate in that article is that if you took away the private car, which means that you'd still have taxis, you'd still have freight delivery, and still have buses.

The real issue is a spatial issue, which is why we, as designers, need to get in the mix in this conversation.

Buses, I think, are really critical, because a lot of people think of buses, these incredibly, sort of, archaic, slow-moving ways of getting around cities. But the reason they move so slowly, is because they're constantly trying to navigate this field of private vehicles. When you take private vehicles away, buses and trucks, or smaller mini-buses, electric mini-buses, can move lots of people around. It's the rubber tire technology; it's flexible, so as different parts of the cities grow and change, the bus routes can change.

I just think there's a huge opportunity for us to move around our cities in a much easier way. So, when you say, “Well, why is this about more than climate change?” [I’d say] well, first of all, the climate impacts are just enormous. You're talking about billions of people around the world in our major cities. Just the heat island effects, the air pollution and obviously the carbon emissions, you know, that come from all those private cars, going away would be enormously impactful.

Then beyond that, there's a huge quality of life issue. People often ask me, “What's the future of cities post COVID?” And I believe in cities, and I worked for Mayor Bloomberg after 9/11, [when] everyone thought cities were going to dive in, and they bounced back with a vengeance. I think they're [also] going to bounce back from this with a vengeance.

I think [cities] are going to bounce back from this with a vengeance.

But we do have a competitive situation, in my mind, that is starkly drawn between remote work, and horrible commutes. Meaning that, the people who live in work in the city, they're all going to go back to their office space, because they tend to be in industries—I think, in my office, most of my employees live in New York City, we're going to come back—we need to meet face to face, [make] models, drawings, the things that architects do, right? A lot of people who work in cities are paralegals or insurance brokers, and they have two-hour-long commutes that are really, really horrendous. Those people have a strong vested interest in going to their employer and saying, “You know, I'll work from home. I'll stay in the area, so I can come in for the occasional meeting, but I really don't want that horrible commute every day.”

So, will you pull all the private cars out of a central business district? Well, we were able to illustrate that it's not just about Manhattan, but it dramatically improves commute times for the entire region. So there's an enormous quality of life issue for all of those kinds of people, who are coming back and forth on express buses and things like that. Then there are the quality of life issues on the ground. In New York City, we recently converted 14th Street into a bus/bike way, and yeah, that was great for transportation. But what I don't think we talked about enough during that conversion, is what it meant for the street to be quieter, for it to feel less polluted, for there to be this kind of ballet of people jaywalking freely across the street, because they didn't have to worry about getting run down by a private car. So there are all of these things that are really joyful.

Private cars driving into cities is fundamentally an elite idea.

You know, how we deal with trash in big cities? Can we provide better homeless services, when we pick up all of this space that's used by these tin cans? I just think that as more and more people illustrate that—you know, just this morning, I saw another architecture firm was doing this for a different part of New York City for a specific project—I think people will start to get more and more of this imagery, and say, “That's not eating your spinach, that's actually dessert. It's great. That's the way I want to live.” And you're going to see-change happen around how people want to think about and use our streets. This also will dramatically affect issues of equity, race, and affordability, because a lot of communities of colour are often in places that have horrible commutes.

There's this way in which what we're talking about would flatten the access to the city, in a way that is very hierarchical and very elite right now, because private cars driving into cities is fundamentally an elite idea. I just think this is inevitable, as we think about a more ecological and equitable world, fuelled by cities where most people live.

Martin: I might challenge you on this a little bit. While I fundamentally agree with everything you say, I'm not sure that every listener will. And one of the things you said is that cars are fundamentally, at their core, kind of an elitist principle or mechanism for travel. Actually, even as noted in the article by Farhad, cars are a status symbol. Where we live, in Central Europe, and even as you go further east, in Europe, the cars are what you buy when you’ve “made it.” You know, you drive a BMW because you got a big job, and that wasn't something that was always available to every society. So, I think making people believe that it's better to, kind of, use a shared car or use a taxi or share a taxi or something, is harder to do, though. How do you do that?

Vishaan: Well, I mean, I always welcome disagreement. But you're actually getting to the crux of something that I think is really important, which is you can talk about these things in terms of data, in terms of climate science, and what people should do. But if you only do that, you're missing one of the biggest components, the cultural component, which is really what you're asking about. That's what the status symbol is, right? It's a cultural artifact. And you then have to say, “Well, why is that the status symbol? Why is owning that BMW..”—and by the way, if you talk to BMW or Ford, or any of these big auto manufacturers, they also see this as an inevitability they're all turning into mobility technology companies, non-private vehicle companies—but, you know, there's two aspects about this.

When the idea of the “American dream” was first born [it] was not about cars and houses. It was actually about equal opportunity.

One is, why is that—car ownership—a symbol of status? That is something that is almost purely an American phenomena that then got spread worldwide. I saw it happen in India, and I've seen it in Brazil, in Saudi Arabia and China, and, interestingly, a bit less so, in a lot of the East Asian tiger countries. You see it, [but] you don't see that same phenomena play out in Korea, in Japan, in Vietnam, in the same way because obviously, more land-scarce countries don't think quite the same way about these issues, right? Because for them, car ownership tends to equate to traffic and congestion and expense in a way that it doesn't if you live in the middle of a vast expanse, like you know, the United States or Canada.

So what I think has to change—you know, what we're talking about—is that status symbol, in my mind, is completely driven by the American dream. And the American dream, as it was concocted—what's really interesting is, if you look at the 1930s, when the idea of the “American dream” was first born, and I talked about this in my first book—was not about cars and houses. It was actually about equal opportunity. The first time you hear mention of the “American dream,” it is about achieving equal opportunity, regardless of a person's status, race, or gender. [This was a] really, really radical idea, going back to the 1930s.

If billions of people around the world start living the way wealthy Westerners live, with big cars and big houses, we're screwed. The planet cannot withstand.

By the time we get into the post war era, when the war machine of the United States is sort of corporatized, there's a famous cartel that was formed to get rid of mass transit. And the advertising machine that you see depicted in Mad Men, goes into full force. This idea that success is equated with the owning of stuff, is a dramatic cultural shift that happens after World War II. And then with, I think, technology and broadband in the 1990s, and the opening up of economies and neoliberalism spreading as a kind of ideology, and Deng Xiaoping saying that “to be rich is glorious,” suddenly, you see the entire world gravitate towards that idea that status is about stuff.

The fundamental challenge that presents, of course, is that in terms of climate, we've had 2 billion people enter the middle class in the last two decades in this world. And if billions of people around the world start living the way wealthy Westerners live, with big cars and big houses, we're screwed. The planet cannot withstand the resource demand of billions of people around the world living that way. I see it; one of the scariest experiences I ever had was [when] I took a low flying flight around Riyadh, the deserts around Riyadh, which looked just like Phoenix, these irrigated deserts that are all built around vehicular infrastructure. We can't sustain that; 10 billion people cannot live on the planet this way.

I think, in the future we might start seeing cars as social stigma, that people will start being embarrassed by the fact that they drive places.

So, really, younger generations have to rethink the status idea. You know, you think about the way the water bottle, the reusable water bottle, became a different form of status. [Thinking] “uh, you're using a plastic bottle?,” the way in which we started thinking about cigarettes; it’s [almost] becoming this social stigma. I think, in the future we might start seeing cars as social stigma, that people will start being embarrassed by the fact that they drive places. So, I just think that that's a huge cultural shift that I start to see young people leading.

Martin: Yeah, I think you're totally right. Well, all of your arguments are backed by the data; the precipitous drop in the amount of Gen Zers that are getting their licences is scaring the hell out of Ford and GM, and all these companies. Which is why, as you said, they're becoming mobility companies, and even companies like BMW are getting into housing.

So, I think this is definitely a trend. I think the technology solves some of the issues that you're talking about, but then it gets to the question of: Who's going to own cars in the future? Are cars going to be owned by cities? Are cities going to [have] fleets of driverless vehicles? I think you've got something to say about driverless vehicles, because some of us are frustrated by how long it has taken to get this kind of perfect feature—where the car drops me off, and just disappears into the darkness, and comes back when I need it. So, how does this help or hurt the argumentation?

Vishaan: I’m not at all pollyannaish about driverless vehicles. First of all, I looked at the technology fairly closely, and the problem with it is, it only works in environments where every car is a driverless vehicle. It works fabulously then, if you can set up a Disneyland type of environment where every single car is a driverless vehicle. It works fabulously, as soon as it has to. I love that, you know, Silicon Valley calls regular cars, “legacy vehicles,” now. So, the idea that a driverless vehicle has to interact with a legacy vehicle becomes deeply problematic. And in fact, this could very quickly turn into our next version of the gated community, where there are certain, kind of, elite communities that only have driverless cars.

I just think that people are not thoughtful when they talk about these utopian ideas and the enormous social impact that they may have.

And, a lot of the tech companies are toying with this idea. I've seen drawings where, you know, you'll see a city drawn as a sort of driverless boundary, and then ringing that boundary is a series of parking garages, where you park your legacy vehicle and transfer to a driverless car. And it's absolutely horrifying. It's horrifying. The other thing about it is, driving, in the United States, is the largest employer of high-school-educated men. If you want to create a civil war, and you think things are bad now, when you displace millions of people, when the only answer from elites is, “Well, you should get retrained; you shouldn't be a driver.” ..I just think that people are not thoughtful when they talk about these utopian ideas and the enormous social impact that they may have.

Not to mention, there's all sorts of studies that say that driverless cars could dramatically increase traffic in cities. So, I just think we need to be super, super cautious about all of this stuff. Because, see, in my mind, going back to where we started—because I, for years, taught a class called “Theory of City Form,” and it kind of starts with how cities formed around grids of streets and plazas, and so forth—so, streets are a many thousands of years old invention. The first sidewalks are like 2000 years old. And so that infrastructure, streets and sidewalks, started well before the invention of the internal combustion engine. And it was really about the streets being a social condenser and being a place for, sort of, serendipitous exchange, and for social value.

When the internal combustion engine was invented, it completely changed our worldview around the idea that streets weren't for people, that streets were for cars.

And when the internal combustion engine was invented, it completely changed our worldview around the idea that streets weren't for people, that streets were for cars. Which is why what we proposed in the New York Times looks so radical, even though it's a kind of “Back to the Future” idea. I just think that we have to be super careful about technological panaceas. Because the car was presented as precisely that kind of silver bullet, and I just think silver bullets can be a lot more dangerous than we think they are.

Martin: Yeah, I would agree with all of this. And I get asked a lot about the future of the city. And my answer is kind of disappointing, I think, for people, because I say [that] the future of the city looks a lot like the past, and people don't really understand that. But basically, you've illustrated it in your proposal; it means that there [will be] a lot more walkability, we [will be] living in a sort of 15-minute city, we [will be] able to kind of live, work, and play in the same neighbourhoods; this is what I think. I'm 40, but I think my generation and below, and definitely younger people, don't want to spend time in the car. So I do believe that time is on our side in this argument. And I think, in the next two decades things will have to change.

Vishaan: I have an 18-year-old [son] and he doesn't have a driver's licence. He has no interest in getting a driver's licence, and none of his friends have any interest in getting a driver’s license. And people say, “Well, sure, that's because they're young. Wait till they have kids.” I don't know. I'm not sure that's true.

Martin: I sold my car like 15 years ago, and I never looked back, you know. We rent a car occasionally, and we love that. We can change cars every couple months for the weekend.

Vishaan: Yeah, you know, that's one of the ironic parts about my existence. I actually love cars, I just don't drive them in cities. I've driven across the United States three times. And I just think when you're talking about these larger landscapes, especially rural landscapes, cars are extraordinary. And I do think we need, obviously, cleaner cars, right? And that sense of open road and freedom.

It's going to turn into a, kind of, rights and freedom argument—the freedom of movement, the freedom to go where I want to go.

You asked a question a while back, which is: Do you imagine all cars will be owned by municipalities? And this is going to turn into a political issue akin to guns, because it's going to turn into a, kind of, rights and freedom argument—the freedom of movement, the freedom to go where I want to go. And now I've got, between government and big tech, kind of, “Big Brother” saying what car I can drive and where I can go. And, you know, that's going to turn into a huge political fight. I've already seen it in the United States; there's an enormous correlation between Trump voters, gun ownership, and the ownership of very, very large cars. Because they're all expressions of freedom, as they see it.

So I think we need to be careful, because I do think, in a big city, that most cars should be fleet vehicles, shared, electric, solar, you know, all of that good stuff. But, you know, do I want [to have the] ability to go drive a [Porsche] 911 on a back country road? Yeah, I do. And I think we need to understand and balance this conversation with that, because without it, we're losing a huge segment of the population that I think would otherwise be on our side.

Martin: Yeah, the political argument is going to be tough, and it's going to take a long time. But I think the natural course of the consumer is kind of leading us in that direction. The places to look, I think, are like Singapore; you know, if you live in Singapore, it's tremendously expensive to own a car. So, it does become, sort of, an elitist symbol or status symbol. On the other hand, I think the city has done a good job of controlling the amount of car ownership, so you get there by, unfortunately, taxing it and making it prohibitively expensive for everyone to have one. But, I think that's generally the way it's going to go.

The way in which I think it makes it easier to get there and to get to a proposal like you have, is in cities like New York, which have an unbelievably efficient public transit system and robust one. Of course, as New Yorkers, we all know, it needs to be better, but it's robust. And I think the pandemic is showing that public transportation is also not everyone's preferred route of transportation. I think dense cities have gotten a bad rap, and so has public transit. Do you think that's a long term issue? Or do you think people are going to sort of say, “Okay, I definitely don't want to drive two hours from Suffolk County to Manhattan this week for work. So, I'll hop on the Long Island Railroad.” Again, this is going to be a long term problem: Are we going to see [people] driving just because they're scared?

Vishaan: I don't think it's going to be a long term problem, because people aren't going to have a lot of choices. You know, there are 83 lanes of traffic that come into Manhattan, and there's not going to be [an] 84th anytime soon. So, people need to get to their jobs; most people are going to have to return to their jobs. You know, there's still headquarters buildings being built in New York City right now. I think that all of that will return. But the one return problem is, first of all, the pandemic is creating a huge budgetary problem for mass transit systems. Right? So, metro systems are going bankrupt, and unless there [will be] federal bailouts, we're gonna have huge problems with them.

I think that's the much longer-term issue; for people to use mass transit, again, it's a quality of life thing.

On top of that, most mass transit systems, especially in the United States, much less so in Europe, are archaic; they were built 100-plus years ago and they’re simply not in a state of good repair. They haven't extended out to places where people live in; cities have grown. I think that's the much longer-term issue; for people to use mass transit, again, it's a quality of life thing. That's why I place a lot of my faith in the future of buses, especially smaller buses.

You know, in India, they use a lot of mini-buses that are gasoline driven, but they're 20-passenger buses, you can only sit in a lot of them. And, you know, those provide great point-to-point last-mile solutions with relatively cheap technology. And if you can then turn those into electric, zero-emission vehicles, I think you can do a lot with that. I think it's a very adaptable, very flexible technology that can be very, very fast if it’s not competing with cars on the road.

Martin: Right. Janette Sadik-Khan is a huge proponent of this idea.

Vishaan: Yeah. Well, she and I were, of course, colleagues in the Bloomberg administration. What Janette understands is [that], when you ban private cars from the central business district, it has a huge knock-on effect for 100 miles outside of that central business district. That central business district is what's generating the majority of the private car demand. So you take that demand away, and all of a sudden it erases a huge number of cars on the road, all over an enormous region. That's what is hard for people to imagine, I think.

When you ban private cars from the central business district, it has a huge knock-on effect for 100 miles outside of that district. That district is what's generating the majority of the private car demand.

Martin: I think you do a really good job of giving visuals that people can kind of hold on to. They can get a sense of what this might feel like to eat on the street and not have tons of cars honking their horns and disrupting their dinner, which is one of the worst parts about having a meal on the sidewalk in a place like New York. Part of this conversation is about street equity, and you talk about street equity and silent majority; it's not really being represented properly. Can you talk a little bit more about that before we get on to the next topic?

Vishaan: Sure. Well, it's fairly straightforward. I mean, the majority of city dwellers in most big cities don't own cars; only about one-eighth of New Yorkers own a private car. And so that seven-eighths has no, or very little, political representation in terms of how the major public spaces in their city, the streets, are used. So, the street equity conversation centers on that political reality, as well as just the fact that, again, it's a spatial thing. If you look at 50 people and 50 cars, versus 50 people on a large bus, the amount of space they take up is enormously different. We have some diagrams that show that.

As designers, one of the key things we can do is help people visualize ideas that are really hard to otherwise grasp.

The other thing about equity, you know—and I'm glad you mentioned the visuals because I think as designers, one of the key things we can do is help people visualise ideas that are really hard to otherwise grasp—we work really hard in those visuals for the times, to not connote some twee, boujee fantasy of what the city can be. But really working with the grit and reality of New York City, like the garbage cans, not just dealing with rich parts of the city, but all parts of the city, rich and poor. I'm dealing with existing street furniture typologies, because that all connotes equity, too. It's about, you know, there's too many of these fantasies that are really driven by a, kind of, upper-middle class that wants to grab their sensibility under what a city is, or should be. So we have worked really hard to avoid that.

Martin: Yeah, and we've talked a lot about New York; I think we both know it really well. So let's talk more about something I don't know as well, because I only lived there for like six months in my life—California. You recently commented about degrowth, and California wildfires, and you talk a lot about sprawl, I think, in this conversation. And I love this, I think you've said it, a Henry David Thoreau quote, “If you love nature, you stay away from it,” or “you shouldn't live in it.” And you say this to support the claim that cities are not responsible for climate change, but sprawl is. What do you see as being effective in disincentivizing sprawl and keeping people in the heart of cities?

Vishaan: Um, I think it's a carrot-and-stick [policy]. The “stick” has to be regulatory, and the way which it’s regulatory is that people have to pay for the negative externalities of their behaviour, which is a fancy way of saying that, you know, when someone pollutes a river, we expect them to pay for the cleanup of it. So, if someone is polluting our atmosphere by living in a McMansion and owning four [Cadillac] Escalades and driving to work every day, they should be taxed extraordinarily heavily for gas taxes, real estate taxes, highway tolls; it should be extraordinarily expensive to live in a sprawling lifestyle. And all of that is not some outsized taxation; it's basically to pay for the pain they're causing the world. So that's the “stick” aspect. And, of course, related to that there's all sorts of regulatory stuff about zoning, about allowing multifamily housing, around transportation, all of those kinds of things.

I should be extraordinarily expensive to live in a sprawling lifestyle.

And then there's the flip side, the “carrot,” which is to say, “Well, do you really want to spend your day, you know, an hour and a half, each direction, in a traffic jam?” Right? So the quality of life argument that I can give you—the most valuable thing that human beings have, which is time—I can give you time back with your family, with your friends, to exercise, to read, to eat well, you know. So, I really think that carrot-stick balance is really important in how we talk about this.

Martin: Do you think this is a national conversation that needs to be had? Like, do we need an urbanist for president or is this going to have to happen on the local level?

Vishaan: That's a really interesting question. You know, it's interesting, I do think Joe Biden gets it. Because he talks about infrastructure more than I think most candidates do. But, look, I am a big believer in cities having a lot of local autonomy and local control, and especially strong mayors. I think mayors are the most important political force in the world right now, in terms of climate change, and social equity. They can work with a lot more alacrity and nimbleness than the federal government can. And so, you know, I'm just a big believer in mayors. You look at what Anne Hidalgo is doing in Paris; it's extraordinary work.

So much of the founding documents of the United States are based on a kind of vicious anti-urbanism.

It'd be nice to have an urbanist as President, but also for the United States—look, Jefferson was a deeply anti-urban man. And so much of the founding documents of the United States are based on a kind of vicious anti-urbanism—with the Electoral College, you know, we're going to have a situation in this country in the not-too-distant future, where 30 senators are going to represent 70% of the population. That's a recipe for disaster. So, we do need federal leadership on all of this, to help unwind these things that the founding fathers either had extraordinary bias about, because they wanted to keep the slave trade and their version of agriculture available to them, or just didn't understand what was gonna happen in the future.

Martin: I definitely want an urbanist for president in the near future; I think Joe Biden does get it, and a lot of the work he did with Obama was on the issues that we care so much about. I almost want there to be a president that understands it, but doesn’t talk too much about it, and just does it quietly.

Vishaan: Right, and it could happen the first time we elect a mayor as president. We had a couple in the running this time; that’ll be an interesting moment, if we can get a mayor into the White House.

I am a big believer in cities having a lot of local autonomy and local control.

Martin: Yeah, I think Mayor Pete [Buttigieg] is our guy, in the future. We talked a lot with one of his advisors, Christopher Cabaldon, and he’s doing a lot of these things in West Sacramento, which isn’t too far from you. So, I think you’re right; a mayor in the White House will do a lot of good, to green and improve our lives in cities. The wildfires have been dramatic—I don’t know what to talk about [that’s] been more dramatic in the past six months—but in California, it seems from afar this is really dramatic. It has upended a lot of my friends’ lives; the story you told earlier has happened to at least three of my friends. They were evacuated, either from their homes or some place they were staying for a weekend.

Vishaan: Yeah, we were evacuated from a hotel; it was really scary, actually.

Martin: Yeah, a friend of mine had the same situation. I’m seeing—you know, my friends send me photographs—the sky is orange over San Francisco; these are kind of apocalyptic scenes. In this analysis, you’ve talked a bit about degrowth as something that California must do altogether. What does degrowth mean?

Vishaan: I’m not sure degrowth is what I mean, as much as just the right kind of growth. I mean, California has to grow; it’s just that it has to grow in multifamily housing in its cities, not in sprawl. It’s funny, my wife isn’t from here, and as we were walking around she was just flabbergasted by how low-rise it is. The entire Bay Area, here in Berkeley, it’s extraordinary how low-rise most of California is. It’s all built around the suspended disbelief of the automobile.

All of our cities are going to grow. All of our urban areas are going to grow; the question is just going to be about how they are going to grow, and the qualities with which they grow.

You know, California has a huge amount of income in growth—and again, it goes back to that larger point I was trying to make, about [reaching] 10 billion people by the year 2100—and all of our cities are going to grow. All of our urban areas are going to grow; the question is just going to be about how they are going to grow, and the qualities with which they grow, which is what my TED Talk is about. It’s about quality; I never argue for “degrowth,” per say, it’s just that I argue against sprawl, because obviously, if 10 billion people try to live that way, we’re screwed.

Related: Vishaan Chakrabarti "How We Can Design Timeless Cities for Our Collective Future"

Martin: Yeah, we have [about] 10 minutes left, Vishaan, so I’ve got a couple of questions that our audience submitted before this. I think a lot of people were excited that you were coming on [the podcast]. A lot of them we have touched on—carless Manhattan, and other climate change issues. One of them we haven’t discussed at all, and it might lead into our last topic, about inequality and racism. One inequality maybe we can touch on, before I open it to you to talk about things you’d like to share with us, [is] how are you incorporating the female experience into urban design? That’s a question from one of our listeners.

Vishaan: That’s a great question. I think that the clear answer is [to] ask females. Ruchika Modi, is the Managing Principal of my office; I work with women all the time. And Berkeley is practically led by women; actually the campus is run by Carol Christ. To me, this is similar to the race questions that we have in our society. I think a lot of dominant culture in the form of single white men—what they’re trying to do right now is maintain their dominance by saying, “Well, you know, we’re just going to hear a bunch of voices.” And I actually think that’s not the answer; the answer is, sometimes you’ve got to step aside and let other people lead.

That’s why I’ve been promoting women in my practice; the three department chairs of my college are all women. And the harder part, frankly, is around race because in our field, only two percent of licensed architects in the United States are African American. So, you can’t just read a bunch of books and somehow substitute for that experience. It means that folks who are marginalized have to lead, and people who have been leading have to step aside, which is a big statement. [It’s] very hard for a lot of people to swallow, but it’s just the reality.

Catherine Bauer wrote the National Housing Act for FDR, she was a vehement anti-racist well before her time, and invented public housing in the United States. She’s, in my mind, way more important than Jane Jacobs, and yet most people haven’t heard of her.

One thing we’re doing in particular, as I mentioned—the two co-founders of my college, William Wurster, the Dean, and his spouse Catherine Bauer Wurster, who is arguably the more important person between the two. Catherine Bauer wrote the National Housing Act for FDR, she was a vehement anti-racist well before her time, she advised five presidents, and basically invented public housing in the United States. She’s, in my mind, way more important than Jane Jacobs, and yet most people haven’t heard of her.

So we have this whole thing called the Bauer-Wurster Initiative going on right now in our college about helping people understand her history, but also understanding why what she spoke about was so relevant to the people of our day. You know, she understood things; she wrote about people’s domestic lives and how families interacted in housing, things that I think men wouldn’t have written about during that time. So, I think it’s about putting those perspectives into leadership.

Martin: And what kind of actionable measures can we take now? The things you’ve done in your practice are admirable, of course, and in academia, also; you’re setting an example for the rest of us. Anything else that can be done by anyone out there that would lead to more equitable representation up ahead?

It means talking to people who don’t agree with you, hearing out their perspectives, and then pushing for the change you believe in.

Vishaan: Well, I would just ask people to think about how to organize large scale action, because I think too much environmentalism or racial consciousness has turned into this personal mission. It’s what lightbulb I use, what food I eat, and what books I read. That’s fine, but people can’t expect that that’s going to have a scale[able] impact. So what’s really important for especially young activists to do is to figure out how to organize and push governments, push society, push academia, push our institutions toward reform.

It’s a long, hard slog, and a lot of these things do not have binary answers. It means talking to people who don’t agree with you, hearing out their perspectives, and then pushing for the change you believe in. And it’s not easy, it’s a lifetime’s work. It’s an asymptote; you’re never going to get it right. So, that’s a hard thing to stomach but I think it’s critically important to understand.

Martin: Yeah, in fact, it’s kind of a nice way to wrap up. The whole reason that I founded reSITE was to bring people together, to talk about things that [we] might not necessarily want to talk about. But, those are the issues and those are the frictions that will help us develop a better city. In that, what would you like to talk about? There are only a couple minutes left now. Is there something that I missed or something that’s, kind of, burning for you? Is any of this influenced by your recent move to California? What’s next?

I think that so much of what gets built around the world is this kind of banal, homogeneous stuff that makes people reject density and reject urbanity.

Vishaan: Well, I guess, maybe the only thing that we haven’t talked about much is design itself. Design, as a pedagogy, as an ethos, is undergoing huge change. We’re having conversations about how racialized the teaching of design is, how design actually directly addresses climate change, and kind of the tropes of green buildings and fluorescent light bulbs.

I really believe that design is a huge part of this mix, because you can’t talk about fighting urban sprawl and transit-oriented density and all of these things again without quality, and without creating a sense of belonging for people. I think that so much of what gets built around the world is this kind of banal, homogeneous stuff that makes people reject density and reject urbanity.

And I think designers have a very, very disciplinary-specific fight on their hands, having to do with creating—again, not just quality—but how one creates an architecture of belonging.

And I think designers have a very, very disciplinary-specific fight on their hands, having to do with creating—again, not just quality—but how one creates an architecture of belonging. So, that’s something I’m focused on; I don’t have any clear answers yet. Again, I think it’s a life’s work, but it’s something that I’m focused on in my next book, and that we’re focused on in the practice. To me it’s kind of an interesting question mark to end the conversation with.

Martin: Yeah, one what scale can design really impact us? Because, I think, getting back to the original proposal we talked about, oftentimes when we’ve heard about these kinds of proposals from Enrique Peñalosa or others that wanted to see greener streets, or cycling streets, in large cities, it was like a really, kind of, planned discussion. And it didn’t really show us what the city might look like, and I think maybe that’s what you’re getting at, that if we’re going into these conversations as designers, as architects, it needs to have a physicality that resonates with people, that elicits emotion, and that maybe can help drive the conversation. Is that design’s role, maybe?

Vishaan: Yeah, exactly, and design is very relevant to that, I think. Designers, and others [in disciplines] like landscape architecture and architecture; we’ve been struggling for relevance for a long time. I think this could be our moment.

Martin: Ok, thank you so much, Vishaan. Hang in there; I know that you have added complications as the dean of a school that’s now [conducting] remote learning and dealing with the wildfires, while we’re dealing with everything else. Keep your head up, stay positive, and keep inspiring us. Thanks for joining us.

Vishaan: Thanks, I really appreciate it.

That was Vishaan Chakrabarti, Founder + Creative Director of Practice for Architecture and Urbanism (PAU) as well as the Dean of the William W. Wurster College of Environmental Design at the University of California, Berkeley.

Design and the City was recorded at the WeWork offices in Prague, with the support of the Czech Ministry of Culture and Nano Energies. This podcast is produced by Alexandra Siebenthal, with support from Martin Barry, Radka Ondrackova, Elizabeth Mills and Elizabeth Novacek and edited by LittleBig Studio.

Podcast is supported by

More from Design and the City

Winy Maas on Dipping Our Planet in Green

Design and the City is back with the first episode of our second season featuring co-founder of MVRDV, Winy Maas, in conversation with Martin Barry on greening our cities, his latest projects, and how constructive criticism leads to productivity. Listen now!

Design and the City is Back!

Throughout 2020, many thoughts and questions have arisen in the cities close to our hearts. We’d like to discuss what challenges define the discourse today. In the new season of reSITE’s podcast, Design and the City, we will revisit all aspects of future-proof city-making.

Giving Design a Higher Purpose with Ravi Naidoo

Ravi Naidoo, the driving force behind Design Indaba, arguably the most influential design event in the world. The event takes place annually in Cape Town is only the tip of the iceberg. Listen as he pushes the boundaries of the purpose design holds with the simple question—what is design for? Photo courtesy of Design Indaba

Regenerating Cities, Transforming Communities with Christopher Cabaldon

Throughout Christopher Cabaldon on-going, 20-year-long seat in office, West Sacramento underwent has undergone and incredible transformation from a former industrial town to an urbanized, livable community. Hear from the man behind the city’s outstanding urban regeneration.

Related Talks

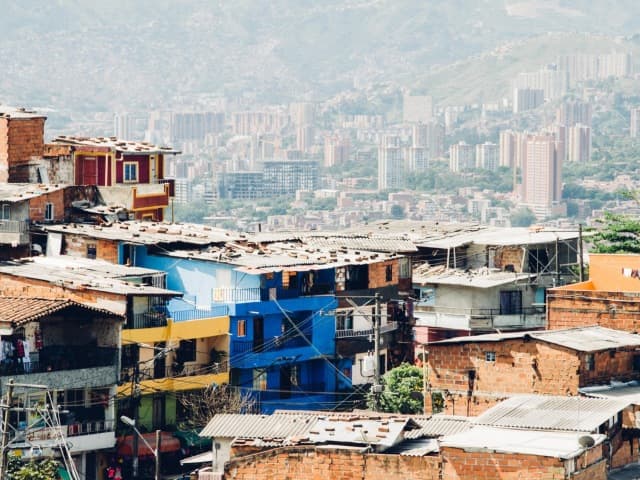

Enrique Peñalosa on Why Equality in Cities Begins with Sidewalks

In order to create equitable urban spaces, citizens ability to move freely and safely throughout the city is paramount. Enrique Peñalosa, the former Mayor of Bogota, Colombia discusses the importance of learning from the disastrous mistakes of 20th-century urbanization.

Obstacles to Building Equitable Cities with Enrique Peñalosa

For Enrique Peñalosa, improving cities means increasing the quality of life in public spaces that create equality between citizens. He argues that inequality is the biggest obstacle to creating cities with a healthy democracy, especially when the last hundred years we’ve built our cities for cars and not people.

Michael Sorkin on Developing Urban Autonomy

Architectural critic and urban designer Michael Sorkin speaks on how the idea of urban autonomy permeates his projects. Rather than developing a uniform model for international urbanism, Sorkin calls for an appreciation for the people who inhabit informal urban areas.

Ravi Naidoo on Creating a Better World Through Creativity

Ravi Naidoo, the founder of the South African "think-tank, do-tank"- Design Indaba - brings about the idea of a better world through creativity with the fundamental belief that design has the power to enhance democracy, elevate cultural identity, improve the quality of life, and act in the service of people.