Race, Space, and Urban Transformation

With urban spaces under the control of protests against police brutality, questions of who gets to utilize a space and who feels comfortable in a space are at the forefront of international attention. Spaces do not randomly appear, and are shaped by their designers, begging the question of the role of urban designers and architects in perpetuating racial injustice.

The eruption of protests in the wake of the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers, spreading as far as Paris, which has seen protests over the killing of Adama Traoré by police in the city in 2016, has brought about a long-needed conversation about how our shared spaces are experienced drastically differently based on the color of one's skin.

The viral video of a white woman in New York City making a false claim to the NYPD on Christian Cooper underlines this phenomenon. Her emphasis on the color of his skin as a means to draw a quicker reaction from law enforcement demonstrates the mutual understanding that black men in public space are perceived as more dangerous. As CityLab pointed out, “policies intended to foster feelings of safety and liberation can also invite more anxiety for black people so long as they are viewed as threatening, or, at best, with suspicion in public spaces. This becomes more magnified under the mandate of wearing masks, which under any other circumstance would invite an even more prejudiced view of black people.” While that interaction could have ended much worse than it did, we can see how another call made to police ended in the unnecessary death of an unarmed black man.

Related: The Diversity Matters in Vienna: Ursula Struppe

A multitude of “urbanist fantasies” as Alissa Walker’s criticism argued, have emerged as solutions to urban crises in post-COVID-19 urban space directly attacks many of the issues of the field today. The prioritizing of urban projects for individualist gains, or the failure to address systemic problems in proposals for ‘better’ urban areas in a post-COVID-19 city, also imperil any proposal for larger change in urban space in the wake of ongoing protests. “If the coronavirus has made anything clear, it’s that cities cannot be fixed if we do not insist on dismantling the racial, economic, and environmental inequities that have made the pandemic deadlier for low-income and nonwhite residents.” Continuing on that “perpetuating the delusion that all cities need are denser neighborhoods, more parks, and open streets to magically become 'fairer' is a dangerous sentiment”.

The push for more green spaces, public transit, or city squares may sound appealing, but the construction of these spaces cannot mitigate the impacts of racism or larger patterns of aggression in policing, especially in response to violent responses from police in response to protest. As founder of McMansion Hell, Kate Wagner, explains, “when we critics say "carceral urbanism" that means putting technocratic solutions like bike lanes, bus lanes and bike shares before equity; before doing the political work to ensure those resources will be not be turned or used as leverage against the communities they're in.”

Related: Nothing in Between: Integration or Exclusion. A Story of Gdansk

With many municipalities on more limited budgets than usual, the expansion of metro systems or painting of new bike lanes comes at the expense of programs that could challenge racial hierarchy in space. The enforcement of social distancing laws in New York resulted in the arrest of 40 people in Brooklyn, 35 of whom were Black. No expansion of the subway or bus lines to Black communities in New York would have prevented this type of enforcement of social distancing laws. Not that the expansion of public transit wouldn’t have benefits to travellers bogged down by a system that doesn’t fully extend to many neighborhoods wouldn’t have benefits, such as making it easier for residents of lower-income neighborhoods to get to work, but the city’s transit system has also served as a space for racism in policing.

Thinking about race and urban space in the wake of both COVID-19 and ongoing protests must also not only address reforms through state measures, although recent decisions such as those of diverting funding from policing to education and healthcare have potential to lead to remakings of space in forms that are less grotesquely racialized, they do not account for those not counted. Campaigns occurring in cities like Bogota, where residents can hang red banners from their windows when in need of help, black banners when facing violent situations, and blue banners when in need of medical assistance, do not exclude residents who are not counted in formal measures like censuses.

Related: Michael Sorkin on Why Public Space Belongs to People

The projects of architects and urbanists in the remaking of public spaces can never be thought of outside of their political and social implications. As Michael Sorkin reminded us, architecture is “never non-political.” Large firms like AECOM have come under fire for participating in the #BlackoutTuesday movement on social media while being awarded contracts to design the literal and figurative structures that so often drive racial inequalities, such as New York City’s prisons. Regardless of any design imperative to build more ethical incarceration centers, as problematic as that is in-and-of-itself, there is nothing stopping a newly designed prison from not exacerbating the inherent inequalities and cruelties of incarceration.

However, there are numerous architects and urbanists with proposals for the construction of space in ways that seek to both challenge existing relations of race and space, and to think about racialized experiences in future spaces. The Bartlett has published a guide for teaching “‘Race’ and Space” in the built environment, offering both tools for its own instructors and additional resources from those who have been addressing this question long before it came near the forefront of popular discourse.

Related: How Border Zones Became a Physicalization of Fear with Teddy Cruz

Further architectural thinking on race and space have ranged from the challenge of perceptions of colonial space in the Carter’s “Apeshit” music video, to the moral failure of remaining neutral in Teddy Cruz’s talk on border zones. Jackie Wang’s Carceral Capitalism presents an in-depth view of how capitalism furthers racist policing in the United States, and how America’s carceral systems are deeply intertwined with its economic forces.

It is important for those interested in architecture and urbanism to look past typical sources of information in order to seek out the perspectives of those who are not fairly represented or equally treated in the industry. It is a conversation we need to continue until realizing that the utopian shared space found in those “urbanist fantasties” is a possibility.

Below are some resources for those interested in these perspectives, and to take action to assist those currently fighting for racial justice in their communities:

More ideas on Designing Anti-Racist Public Spaces

Eight Talks on Using Design to Solve Urban Inequalities

Can design be used to solve urban inequalities? Hear eight talks from reSITE speakers with examples on how we can use the built environment as a tool for social impact.

Systemic Racism is by Design

We’ve taken a backseat to listen and to reflect on ways we have been complicit in institutional racism, and how we can implement more inclusive anti-racist actions. Photo by Clay Banks.

Emmanuel Pratt on Regenerating Urban Ecology

Emmanuel Pratt, MacArthur fellow and founder of Sweet Water Foundation, regenerates neighborhoods by fusing architecture & community development.

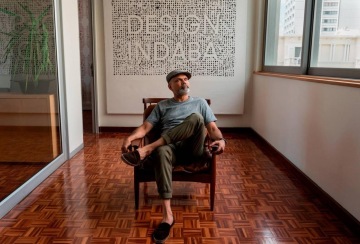

Giving Design a Higher Purpose with Ravi Naidoo

Ravi Naidoo, the driving force behind Design Indaba, arguably the most influential design event in the world. The event takes place annually in Cape Town is only the tip of the iceberg. Listen as he pushes the boundaries of the purpose design holds with the simple question—what is design for? Photo courtesy of Design Indaba