A New Generation of Architects with Chris Precht

Chris Precht’s aim to reconnect our lives to our food production by bringing it back into our cities and our minds can be found throughout his architecture. Listen as he discusses the importance of authenticity, creating spaces that activate our senses, and looking at our objective reality to solve the problems of our time.

As an architect, you always think about visions. You’re always in this kind of this fictional world. Right? Because you always think about future buildings and so forth. So it is a good kind of balance to go to reality, to go to nature to be part of the kind of an ecosystem.

Listen to Chris Precht on Design and the City now:

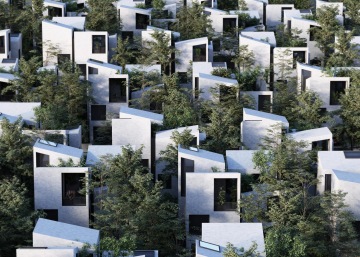

reSITE: When it comes to urban regeneration, not many are thinking about it the way Chris Precht is. Chris is an Austrian architect hailing from the Austrian mountains, but I’ll let him introduce himself to you. If you’ve spent any time in the realm of social media, you may have come across Studio Precht’s stunning images of modular buildings with interwoven, natural geometry that bring “being green” to a whole other level. They are all variations on theme - vertical farming meant for city-living.

Aside from just how eye-catching they are, they serve an important purpose - to reconnect our lives to our food production by bringing it back into our cities, and our minds through architecture. And as civilization was once shaped by food, and it might be the key to the future of regenerating cities. Our discussion begins there and on the kind of stories like these that drive us—as people and as architects.

Chris Precht: Yuval Noah Harai said that we are driven by fiction stories. Stories that we’ve invented. Stories that just exist because we all agree that they exist. Stories like money, religions, nations, borders, the economic system. The same is true about architecture.

Architecture was always driven by fictional stories. We built the pyramids for Gods, castles for Kings, palaces for Queens, now we are building to make a profit in an economic system. We all care about those stories, but our planet doesn’t. If we are not able to connect ourselves to our objective reality, then I do not see any chance that we are able to solve the problems of our time.

We care about fictional stories. Our planet doesn't.

reSITE: That was Chris Precht’s lecture during reSITE 2019 REGENERATE. He kicked off his lecture by talking about some of his biggest childhood influences. Including his father, a well-known freestyle rock climber, meaning he scaled mountains with just himself and the rocks. We asked Chris more about his influences.

Precht: Maybe how my upbringing of being a child influences the thoughts I have as a grown-up and an architect. My dad, he was a pretty famous climber. He was a crazy climber, he did everything free solo, so without any ropes, without security. That means he was really connected to our natural environment in a 3-dimensional way. If I asked him why he did that, he would say, well because in this moment he is connected to himself—to his senses, to his feelings, to his emotions, but also to the here and now. He was living in this real objective reality.

I think that this one also captures my mind as an architect. How can we build buildings that introduce an objective reality back in our buildings? Nature and ecosystems— really connecting to our senses and our feelings. I think how my dad actually spent his life in the mountains really influences me as an architect now, as well.

reSITE: We asked Chris to tell us a little bit about himself, like what it was like growing up in the Austrian mountains, his experiences in Beijing, and what returning to his roots has meant to him as an architect.

Precht: I grew up in the mountains of Austria. Then we started our office, my wife and [I], together in Beijing. After 3 years we relocated back to my hometown - not really, but back to the mountains in Austria. And from there now, we're running a small studio called Studio Precht. Before we founded a studio called Penda, and we renamed it now to studio Precht. From there we work on projects that are mainly global, so very international projects.

It’s a special place but I think I had to go away, you know, for some time to really recognise how beautiful my home actually is. Because if you ever if you're always stuck in this place, you don’t recognise it. If you go to other places then you really feel gratitude.

reSITE: With a relocation came both a new perspective and a new name, so we were curious about the meaning and inspiration behind their first studio’s name, and why the decision to rebrand was important for them as creators.

In the countryside, I think it's not so much about branding yourself, but being authentic.

Precht: It wasn’t that creative. It was just a mixture of our names. It was actually really boring. I think that this rebranding came because we now operate on the countryside. Actually having a synonym for what you're doing, it doesn't seem really authentic. In the countryside, I think it's not so much about branding yourself, but being authentic so you want to stand with your name for what you were doing. That’s why we rebranded.

reSITE: But there's more to the story about their rebranding, and decision to relocate. It wasn’t an easy one for Chris and Fei Precht, his co-founder, and wife, but it was an important one. They made the decision to close their successful three-year-old Beijing-based studio, Prenda, setting out back to Chris’s roots in the Austrian countryside in order to seek more harmony and stability in their lives.

Precht: It keeps us balanced I think. You know, in the city there is much more hustling. You feel that you have to always be places, so you are surrounded by distractions, so that's not really in the countryside. In the mountains, there are no distractions. You can go to the mountains, to the forests and find balance. I think that's in general good as an architect because, as an architect you always think about visions. You always think about this kind of this fictional world. Right? Because you always think about future buildings and so forth. So it is a good kind of balance to go to reality, to go to nature to be part of the kind of an ecosystem.

It’s always very fast and things need to happen immediately and you, as an architect, you are also adapting to this kind of lifestyle, right? And so, I was hustling a lot for new projects, to fly to clients. For me success, during [my] time in China, it meant that I have to grow my business, that I want to grow my projects, that I want to grow my team, my fame and so forth, right? It was like a hamster in a wheel - always running. Now I think in the countryside, success for me means something different. I don't need to be the most famous architect or the most known architect or richest architect, or whatever. I want to be a happy architect. So we achieved that now.

I think that means also regenerating your head and your mind because those are the most important tools for an architect.

I’m really, really happy with what we are doing. We downsized the office a lot. Now we have a very small studio with a couple of people and we really choose our projects that we take on very carefully so we don't take on a lot of projects per year. We select them very carefully, and put quality over quantity.

I think like this, you know, to create also a work-life balance through that, that you downsize, that means for me, that I can regenerate between architecture, which I truly love and I’m passionate about, but it's not the most important thing in life. So you value things a little bit different, you put a little bit of a different hierarchy into place. I think that means also regenerating your head and your mind because those are the most important tools for an architect.

reSITE: In order to regenerate our cities, we must be able to regenerate ourselves, to be able to show up, and to deliver as much energy and creativity as we can towards whatever it is we wish to create, and in our case, in terms of placemaking. For Chris, it’s spending time in the mountains, utilizing it as the year-around playground that it is. But the mountains, as we know, are harsh, unforgiving places and that is part of their magic.

Precht: We are in the mountains right, so we do everything that somehow deals with mountains. We climb, we hike, we go on ski touring, we ski. This is so special, you know, you take your mind for a walk. That means pure regeneration. If you eat an apple on 3000 meter altitude this tastes better than any gourmet New York restaurant.

It teaches you that you have to work for real gratitude, and real gratification. You know, this one doesn't necessarily come at your tip of your finger - at the moment we get gratification very easily - a like on Instagram or we can go to any restaurant to eat whatever we want, so we can have everything we want immediately. Real gratification means that you have to put time and effort in it. Hiking is not necessarily about happiness and being happy all the time. It is about overcoming obstacles, overcoming really bad times during the hike. This one teaches you what real gratification really is. I think is also maybe a lesson for architecture. Architecture is a very long, long paced game. It is a marathon and you need to have a lot of patience for the process.

reSITE: Chris represents a generation of architects who aren’t concerned with theories or concepts but with the environment, with climate change, and with sustainability. He stated, currently, it is very profitable to destroy nature. It is profitable to exploit our ecosystem. Since Studio Precht’s return to the mountains, their projects have taken shape through inspiration drawn from their newfound way of life that inherently counters that. They live off the grid. They grow their own food. They try to live as self-sufficient as possible. And they aim to translate that into their projects, bringing that kind of connection back into the city. Here, Chris is discussing those projects at reSITE 2019 REGENERATE.

Chris Precht at reSITE: We try to find a way to somehow combine in this project on the one hand, architecture, and the other—agriculture. [We try] to somehow combine them and maybe both can profit from each other. So, within the A-frame system, you actually have a space to live, and on the outside, you have a space for gardening. If you translate that to the city, it becomes more interesting.

We create spaces that really reconnect to all of our senses. It creates different city centers. City centers are not defined by banks or corporations but by health and vitality.

I think cities need to be part of the food production of the future. In the next 30 years, more food will be consumed in the last 10,000 years combined and 80% will be consumed in cities. So that means if you want to grow our food closer to its consumption, cities need to be part of that. It actually makes sense to grow food on our buildings. We can think of buildings of the future differently, we can think of it as an ecosystem by itself, of organic loops within the building. Food waste can be transported to the basement, there it decomposes and turns into nutritious soil to reuse in order to grow vegetables. This kind of production of food gets back into our city centers and it's back to our minds.

We reconnect with our food and it’s no mystery anymore how old this food lands on our table. We also create spaces that really reconnect to all of our senses. We create spaces that we want to touch because we use haptic materials, we can listen to because birds and bees are nesting into our buildings, and we can smell, taste and eat parts of our buildings. So really buildings that connect to all of our senses. It creates different city centers. City centers are not defined by banks or corporations but by health and vitality.

reSITE: He continues to discuss this deeper with us during our conversation. He described the impact the disconnect has on the overall well being of both our cities as a whole and the communities we live in.

Precht: I think there is a problem at the moment—what we build and how we build it. So how we build it you know because architecture is very closely connected to the economic system. A lot of developers and investors are going to make a profit, so how buildings are built - sometimes with very cheap materials, materials with a very high ecological footprint.

I think there is a problem at the moment - what we build and how we build it.

I think that is a big problem. The building industry is the most polluting industry on [the] globe. But also what we build, like this international style of concrete frames with curtain-wall facades—somehow we have it in every city. So it doesn't matter if this is Toronto or London or Shanghai, those buildings look the same everywhere now. But all of those places actually have a much different heritage. They had building traditions that are going back thousands of years, but this international style is uniforming our cities and kills all this building traditions.

reSITE: He reminds us that, to explore and discover is something so fundamental in our DNA, and architects have a responsibility to create the ways in which architecture will drive that curiosity. And he’s right, these kinds of inspirational and diverse structures are the kinds of buildings we need to see in our cities.

Precht: It creates a problem that when everything looks the same, no one is really inspired by it. When people are not inspired by buildings, then they don't care for buildings. They don’t care for buildings, then they don't maintain the buildings. So I think that means that a building needs to be reconstructed after 20 years, instead of 50 years, if they would maintain it.

It creates a problem that when everything looks the same, no one is really inspired by it.

And I think that’s a challenge for architects is how can we build buildings that people really care about. I think that brings back a lot of this...how can we create sensible buildings, buildings that really connect to your emotions, to your feelings, and to your senses: with materials that are haptic, that you want to touch, buildings where the birds and bees are inside and you can listen to the building. Or bringing gardens into the buildings, so you can taste, you can smell, and you can eat part of your buildings. Buildings that really connect to all of the senses.

reSITE: The connection to one’s senses is a pillar of Studio Precht designs, making material choices is a crucial variable in achieving the kind of organic living structure they’re after. Chris’s time in Beijing was also spent learning about bamboo as a material, and how to work with it, all from Fei’s grandfather who is a bamboo craftsman.

Precht: The last time I was really inspired was when I was in Bali. And I saw the work of Hapuku. Laurel Hardy, she was leading a puku team, they are creating wonderful bamboo buildings. You really can see, you know, what you can produce out of bamboo as an imperfect material. It’s fascinating, it’s much different buildings then you would see anywhere else. When you take a local material and you have craftsmen in place who can deal with this material. And then you have people who have really have a vision and creativity then you can create much [more] diverse buildings than what you see today in the city. So we also work a lot with bamboo. We also just finished a hotel in Ecuador which is four stories and made out of bamboo. And it’s a fascinating material to work with.

I mean it always depends what you grow and how you manage your forests. It’s the same thing to our forests. So if bamboo becomes a building material, in the larger scale, not just for some lovely projects, somewhere. If bamboo really enters our city, then of course we need to grow much more bamboo. Bamboo grows much faster than trees, so you can use bamboo within 7 years of growing. Bamboo can grow 1.4 meters per day. From this perspective you know it is a very great material to work with. But so is, for example, woods, but as an architect, you always need to know where to use which material, where and which location it fits better.

reSITE: We return to our discussion about how the other ways living in the countryside has impacted the studio’s work, and perspective. One that is contrasted against their experience in Beijing.

Precht: A lot of this is missing of course in the countryside you know when it comes to art, the opportunities you have, the people you meet, but I think that is also very refreshing. It also offers some time in the countryside that you're bored. When was the last time you have been really bored? Now we have our phones with us all the time, so there is no reason anymore to be bored. But, you know, in the countryside they're still sometimes boredom, and I really enjoy that.

For example, in China, they want to bring the smart city towards the countryside, to bring all this quality from the city to the people in the countryside so they don’t need to move to the city. But I think in our terms maybe, in the West we may need to think in a different way - how can we bring the quality of the countryside to the cities? You know, all of this fresh air, nature, all of this regeneration that you have in the countryside, how can this become part of the city? Because the cities will change.

I think the question is not how can we create more information or more intelligence, but [how] to create more consciousness.

The cities will have more technology, they will have more artificial intelligence, they will collect more data, they will be much smarter. We will know more in the city of the future, but I think we will feel much less. I think the question is not how can we create more information or more intelligence, but [how] to create more consciousness. I think the quality of the countryside really can influence the city of the future.

We are a generation that asks what is possible and not necessarily what is profitable. I have a big hope that we are a generation of architects that do not build for fictional stories, but for an objective reality.

reSITE: That is the question, isn’t it? How can we create that consciousness? A consciousness that is capable of driving change. If we want to create real change, it needs to come with a change of system and the change in our mentality. We will wrap up with some hopeful words from Chris Precht at reSITE 2019 REGENERATE.

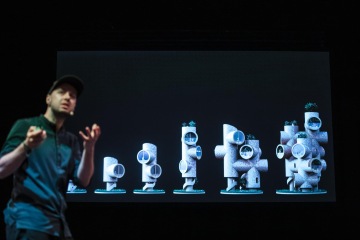

Chris Precht at reSITE: Our generation of architects is not driven anymore by styles, forms, or intellectual theories. Our generation has much bigger problems than that - climate change, global warming, pollution, urbanization or A.I. These are all tasks now of an architect. These are very big challenges, but I'm very hopeful. I think that we are a generation of strategic dreamers. We are a generation that asks what is possible and not necessarily what is profitable. I have a big hope that we are a generation of architects that do not build for fictional stories, but for an objective reality.

That was Chris Precht, Founder of Studio Precht.

Design and the City is brought to you by reSITE and organized as part of the project, Shared Cities: Creative Momentum. This podcast is produced by Radka Ondrackova, Matej Kostruh, Adriana Bielkova, Gil Cienfuegos and Polina Riabukha. It is directed and hosted by Alexandra Siebenthal, and recorded and edited by LittleBig Studio.

Listen to more from Design and the City

Designing on a Human Scale with Thomas Heatherwick

Thomas Heatherwick’s holistic approach brings a thoughtful dimension to architecture, design and urban spaces. Listen to the acclaimed designer along with ArchDaily editor, Christele Harrouk, as they explore how he approaches projects by considering them from a human scale.

Creating Emotional Connections to Nature with Yosuke Hayano

Yosuke Hayano, principal partner for MAD Architects examined how the studio approaches every project with a vision to create a journey for people to connect with nature through architecture. Listen as he draws on specific projects that embody that connection on a macro and micro level. Photo courtesy of MAD Architects

Fighting Gentrification, Berlin-Style with Leona Lynen

A vast, unoccupied administration building in the heart of Berlin at Alexanderplatz - Haus der Statistik - has become a prototype for gentrification done right. Hear from Leona, a member of the cooperative, ZUsammenKUNFT, as she discusses how they are developing a mixed-use urban space oriented towards the common good. Photo courtesy of Nils Koenning

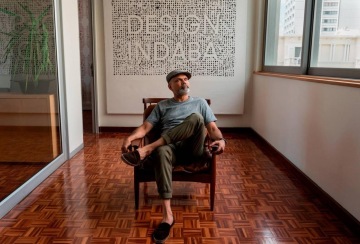

Giving Design a Higher Purpose with Ravi Naidoo

Ravi Naidoo, the driving force behind Design Indaba, arguably the most influential design event in the world. The event takes place annually in Cape Town is only the tip of the iceberg. Listen as he pushes the boundaries of the purpose design holds with the simple question—what is design for? Photo courtesy of Design Indaba