Venice Architecture Biennale: How Will We Live Together with Hashim Sarkis in Conversation with Greg Lindsay

Part two of our Design and the City episode covering the long-awaited 17th Venice Architecture Biennale to explore the question “How will we live together?” and features curator Hashim Sarkis in conversation with Greg Lindsay along with British and Austrian pavilion curators as they explore accessibility on many levels.

The postponed 17th Venice Architecture Biennale asked its 112 participants to consider the question, “How will we live together?”. A question originally posed in 2019 by curator and architect, Hashim Sarkis far before our collective 2020 experience. Sarkis originally asked participants “to imagine spaces in which we can generously live together” Answers from 46 countries materialized into the exhibition of 2021. After a year spent living apart, the theme is both hauntingly fitting and reifies our disconnection.

Listen to part two of our special episodes on the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale on Design and the City now:

It has signalled something, a community eager to reconnect and a deeper understanding of just how interwoven we are with our spaces spanning the full spectrum of human existence. The exhibition explores that spectrum across five scales: Among Diverse Beings, As New Households, As Emerging Communities, Across Borders, and, As One Planet.

For this episode we have it broken down into three parts. The first features none other than the 17th Biennale curator himself, Hashim Sarkis. Hashim is the Dean of the School of Architecture and Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and founder of Hashim Sarkis Studios. Joining him in conversation is NewCities’ Director of Applied Research and reSITE’s own visiting curator, Greg Lindsay, to discuss the meaning and aims of this special Biennale.

17th Venice Architecture Biennale curator, Hashim Sarkis in conversation with Greg Lindsay

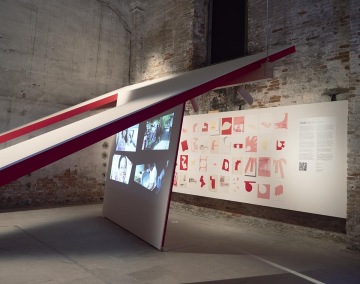

Sarkis’ challenge—“How will we live together?”—was initially posed with reference to the societal impacts of climate change, political turmoil, wealth inequality, among other global crises. But it became even more pertinent with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lindsay, along with his teammates at MIT Architecture’s Future Urban Collectives Lab, proposes answers through their installation Open Collectives, which illustrates how the synergy of the digital and the urban can foster and strengthen new communities. We were excited to host these two in conversation.

Following Sarkis and Lindsay’s conversation, we will explore accessibility and hear from the curators of the British Pavilion entitled The Garden of Privatised Delights and wrap up with the curators of the Austrian Pavilion entitled, We Like Platform Austria. Both sets of curators tackled what can often be a rather serious topic regarding accessibility along with the binary that exists between public and private space, but with a bit of whit and a sense of playfulness, ultimately makes the message on accessibility, accessible in itself. But first, let’s hear from Sarkis and Lindsay.

Greg Lindsay, NewCities + reSITE: Hashim, thanks so much for joining us.

Hashim Sarkis, Curator of the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale: Thank you.

Greg: Obviously, this has been the strangest Biennale, not just because of the pandemic, but because of the extra year the participants had to prepare, including my own team. And so I'm curious how, obviously beyond simply the fact that the pandemic denied us the ability to live together for much of it. So much has changed on the other side of it.

The world is at multiple speeds. Nations have quarantined themselves off. We've seen bubbles in housing markets around the world. I'm curious, coming to the other side of the pandemic, how does architecture and design start to grapple with these questions? Why is design the proper tool for dealing with things like the financialization of housing with borders and quarantines? How do architects assert themselves as having the agency to deal with these problems?

Hashim: This extra year was actually a very challenging one, as you mentioned. Initially, we basically huddled, each into their own world, trying to come to terms with what it could do—to our lives, to our work, and to the Biennale, but that was tertiary almost at that point. But slowly as we began to understand better the situation and what it might entail, and after we postponed the second time until May 2021, we in a way, pressed restart, and started talking again.

This extra year also gave every one of us the opportunity to understand a little bit better, actually much better, the role that architecture plays in our daily lives.

And this extra year gave us more space to talk with each other, not just curators, to individual participants, but across [and] among participants. And that also allowed the national curators to talk among themselves almost for the first time because we've had the opportunity to do that. And that created very interesting synergies, exchange of ideas—at the very practical level, comparing notes as to how people are going to be able to adjust their work to fit the new schedule, to fit the new shipping restrictions, and all.

And I also think that extra year gave us an opportunity to simplify, refine, improve on many of the installations. And because of restrictions on travel and shipping, it also allowed us to reduce the carbon footprint of this event quite dramatically I would say, and I really hope that these changes will stay for Biennales to come even in normal times.

This extra year also gave every one of us the opportunity to understand a little bit better, actually much better, the role that architecture plays in our daily lives. Each one of us all of a sudden became a scenographer of the space behind us on Zoom. Even though we say well, we're in isolation, but actually, that scene behind me represents me on Zoom, and all of a sudden architecture became much more present. We entered people's houses, people's bedrooms, people's living rooms, and even when they didn't want us to look into them, they put a scene of something else, which was also invariably architectural or landscape. So we became very attentive to that aspect of our lives.

The Biennale is not about the pandemic, it is about the causes that led us to the pandemic.

We also began to be much more aware of distances. We now can measure quickly with our eyes, six feet, or three feet, or four feet, depending on our setting. And we became much more aware of how tables are arranged in a restaurant—how a house can also become an office. So, it may very well be that we've been in isolation, but we have become much, much more attentive to the role that architecture plays in shaping our daily lives.

Greg: That's true, but the flip side is also true in the sense of these digital tools, how we're recording this now, you know, always existed, but they have sort of asserted their supremacy in this over the past 18 months. You know, we've seen, you know, these housing shortages, again, in the United States and elsewhere have sort of, you know, led to people fleeing cities. I mean, the whole notion of how we will live together has been challenged. We've seen people desperately try not to live together at all, by purchasing the largest homes in the rural countryside they can.

We've seen, you know, a year of stories about whether this is the end of cities as we know it. And, you know, I've been reading the reviews of the show, of course, you know, the critics say that they asked so many questions, but you know, there's a paucity of answers and solutions to this. And I'm curious where you see the Biennale pointing to. What is the future on the other side of this? We're putting the pandemic behind us, at least in some places, but what features have opened up for us?

Hashim: The Biennale is not about the pandemic, it is about the causes that led us to the pandemic. It is about climate change. It is about how we live together with other species and the planet. It is about increasing political polarisation, and how we can live together across these political divides. It is about growing economic differences and how these are really eroding the idea of a common good, and how we can re-engage that through architecture. It is about mass migrations, and how we can, whether citizens, nomads, tourists, or refugees, find common spaces to live and share. All of these are factors that led us to the pandemic. But this Biennale is not about the pandemic.

The pandemic will probably go away, hopefully, it will go away very soon and we will forget about the two feet, six feet, eight feet. But if we do not address these major issues, other pandemics or other problems will come back to haunt us. That's what this Biennale is about.

If we do not address these major issues, other pandemics or other problems will come back to haunt us.

Now, you asked me about the end of cities, and I want to remind you of a very similar moment that took place during the Second World War when cities were being bombed, and people were leaving central cities elsewhere to go to the countryside and all. And there was a very lively debate in, and among, urban planners and urban designers about where we will be after the end of the war. Some were saying well, “we will now continue to inhabit the countryside, we will be spreading around because of new transportation systems”. And others were saying “no, we will come back to the city as a way to rebuild and reassert the urban presence”.

I would say that after the war, both happened at the same time, or at different degrees in different settings. And I feel that we will probably face a similar situation now. I do also want to point out that those who fled the city are the ones who could afford to. And therefore, if anything, the pandemic or this phenomenon led to an even bigger divide between the rich and the poor. The rich house and the poor house have become much more strongly distinguished through this public health crisis.

Greg: Yes, and my question about this is how can architecture help us repair this inequality, help us repair these quarantines these bridges, again, how is design the right tool for these crises, verses dealing in global taxation rates in all sorts of policy visions as well, how does design reassert itself as a primary tool in helping to, again sort of bridge this, and help us to think about these scales?

This is the sort of thing architects are always asking themselves and are always asserting the fact that they are the makers of cities, and that they are the ones with the power over the public realm to do this. And I'm curious, you know, at a time when people turned away from the office buildings and turned away from the cores of cities—how does architecture as a profession bring its sensibility back to solving these issues?

Hashim: As architects, we are many things and I will distinguish between that, and the planners or urban designers, who are also many things. But primarily, we are the custodians of the contract—the contract to build. And therefore we represent the client in terms of how a project gets to be put together, and therefore we convene structural designers, city employees to help us on the permits—mechanical engineers, programmers, contractors, and designers as well. Sometimes we include interior decorators, sometimes we include other skills. But our skill is in convening and in synthesising the input of all of these people into a solution, or a resolution of a particular project.

We do not solve all the problems alone, but we orchestrate the solutions of problems.

That skill set is a very important one, and it can extend to many situations. We do not solve all the problems alone, but we orchestrate the solutions of problems. That's one aspect of our agency. The other aspect of our agency is that we are, after all, citizens. And there's a certain activism that comes with that and a set of responsibilities that comes with that. Sometimes we can use our tools as architects or skill sets as architects towards that. But sometimes we act as if we are simply citizens. And the confluence of the two sometimes it's important, because it allows us to bring to other citizens a certain level of awareness of their rights to space, their understanding of space.

We are also artists—we express, we represent, we make visible certain phenomena that others cannot see. And this is another level of the agency of architecture, which is this idea of the architectural imaginary.

That's very important also, as an aspect of our agency. But another extremely important aspect of our agency, Greg, is that we are also artists—we express, we represent, we make visible certain phenomena that others cannot see. And this is another level of the agency of architecture, which is this idea of the architectural imaginary, that is very much on display at the Biennale. When dealing with issues like climate change, of course we cannot act alone. But we can make visible the way that political boundaries have ravaged the Amazon. We use architectural representation tools to do that.

Greg: Interesting. Oh, one idea. One question that comes to mind is going back to the elongated time period of planning the Biennale. What ideas at the outset now seem in retrospect absurd to you? What has been discarded? We've talked about whether we're going back to new normals or going back to whatever normal is. I'm curious what did you and your team have, having all this time to rethink the Biennale from scratch, what do you discard as no longer true or no longer worth keeping and, and proceed from there?

Hashim: We did not have the opportunity, luxury, or even the difficulty of having to reimagine the Biennale from scratch. The first time we postponed was February 2020. We were three months away from the finish line. Many people had already packaged their projects in boxes and they were on their way to Venice. We did have the luxury to refine the exhibition and that helped a lot. It sharpened the dialogues that we were trying to create among projects in different rooms, in the way we set them up, in the way we framed the question for every room. It also allowed many of the participants themselves to go back and rethink some of their projects.

We also can help imagine what could be the future of the planet through certain changes, whether in terms of carbon emissions, in terms of connectivity of green spaces, in terms of the impact of geoengineering and what it might do to the planet. We help imagine alternative futures and in that, whether it's at the level of an alternative and better house, or an alternative and better planet, we propose and say, what if? And it's in that skill, that we also can change the world by proposing alternative worlds.

Greg: You've asserted in other interviews, that and that space is defining our social relations as the pandemic has shaped us, right? So the notion of social distancing, the notion of how architectures are defining how we interact during the pandemic, but I'm curious if the opposite isn't also true—that you know that social, social relations and the mental states that many of us have spent the last 18 months in will also affect our architectures going forward as well.

And I'm curious about your thoughts on this about how our spaces shape us and in turn, and what do you think, if anything, there will be a lasting legacy of pandemic architecture? There's been, of course, so much discussion about the Spanish Flu leading to Bauhaus. Is there an architecture of our time that emerges from this on the other side?

Hashim: It's too soon to say at a certain level, especially that most of the signs lead to the observation that the new normal looks very much like the old normal. However, stronger awareness of public health is actually a good thing. A stronger awareness of the fact that we have rights to public open spaces in cities where we don't have the luxury to have open spaces around our houses is a good thing. Taking over sidewalks, or parks for public activities is a good thing. And the realisation that a collective common good is necessary in order to define cities.

The privatization of public space, which has been increasing over the past 50 years, has now somehow been confronted with the reality that these public spaces are needed for leisure, public health, social distancing, education, all of that.

So the privatisation of public space, which has been increasing over the past 50 years, has now somehow been confronted with the reality that these public spaces are needed for leisure, public health, social distancing, education, all of that. And I feel that these kinds of changes will probably stay with us for a little bit longer, and we'll probably settle into a different understanding of what the public realm is.

Greg: Well, there is this question about what, what the, what the public realm is now on the other side—of who these new clients might be. You mentioned climate change, for example. You know, Rafi at our team has talked about the fact that the 20th century—the public was the client leading to social housing and leading to these programmes, and under the neoliberal turn the markets became the client and drove that as well and it raises questions about whether there could be new forms of clients, new ways to initiate projects—whether that is new ways to understand climate change, whether that is sort of non-human participants, I think it's Superflux—really gets into it in the Biennale, and others.

And I'm curious, what do we think about on the other side about new ways to initiate projects, new ways of practising architecture because that theme runs through the Biennale as well? How might we reimagine the profession itself and education as well, to grapple with these problems beyond simply the client, whoever they might be?

Hashim: As we know, the Biennale is organised into five scales, from the scale of the body to the household, to community, to borders and across borders, to the planet. And in the section, As Emerging Communities, we deliberately use the term community, not cities or neighbourhoods, in order to keep it open to possibilities of communities manifesting themselves spatially, in forms other than cities, or that we can understand and identify communities.

Let me give you a very concrete example, in the section As Emerging Communities we invited a group from Armenia called "Tumo", T-U-M-O. Tumo is an after-school programme to help kids in relatively underprivileged communities in the city of Yerevan, but now it's a national programme and actually international to become more digitally educated, to learn about coding to learn about data visualisation, to learn about animation, to learn about AI. And in order to enable those communities even more, they planted their after-hours schools in areas close to these communities, but strategically, near empty spaces where they can create parks, or next to a highway so that they can create an overpass to connect them better.

And over the years, the success of the programme has become such that they are not only providing support education wise, they are providing support to the communities urbanistically—architecturally, urbanistically. And now, the government is turning to them whenever they have a need for an urban design intervention to help frame the project so that it is more inclusive of the communities.

This is the kind of agency that emerging communities are looking for—architects to understand better the nature of their needs, and to turn them out to become less about one sector meaning education, and more about the connectedness among the different sectors. The fact that the government is now using the agency of Tumo to help in urban improvement is a testimony to the success of this group of architects, programmers in creating a very important agency for architecture.

Greg: Interesting, well beyond the scope of the Biennale I'm curious what's on your radar as an educator, as a curator in these new types of hybrids. Obviously our project at the Biennale dwells upon this-- this notion of hybrid physical-digital communities. There's so much attention of course to blockchain, non-fungible tokens, distributed autonomous organisations, there's so much attention to this notion of non-physical communities and also the need for rethinking housing and new types of projects that go beyond the sort of single-use types.

And again, you know, in the context of your work at MIT, and as a curator, I'm curious, you're thinking about what new forms, what new hybrids, what new projects, do you think offer perhaps some of the most opportunities or avenues for architects to explore to rethink what the physical-digital means? Or what you know, housing means, in this context, given the functions that we folded into housing over the last year? How is this affecting the curriculum at MIT and the questions that you were asking?

Hashim: The digital has not replaced the physical. If there's any evidence in this Biennale to that relationship, it is about how they complement each other in different ways. At one very basic level, the production of drawings and now of models is through digital means. At another level, the presence of the machine is, and the computer as well, is very necessary for the activation of many of these installations. They depend on the machine and on the computer a lot.

The digital has not replaced the physical.

At another level, the visualisation that digital brings amplifies some of these experiences rather than replaces them. And so I feel it's not that one is taking over the other. It's that we are at a point right now where we are finding complementarities and continuities in a way that we do not see the seams or the ruptures or the generational shift anymore. It's actually quite smooth.

Greg: Interesting. Well, going back to that, I mean, what does—your students at MIT and a younger generation of architects who are looking at this, I'm very curious about sort of how they are perceiving these relationships, this complementarity between the physical and digital? And, on the other side of this, I mean many students, MIT's included, have spent time doing virtual learning by default. And, you know, while I personally am in favour of face-to-face and believe in the power of space, of design that way, it's been challenged on many levels. And again, I'm curious about how that is, how does this get represented in the curriculum? Or how does this get represented in the projects in the studios that the faculty will pursue?

Hashim: We've talked a lot about the digital entering into our production of architecture, the CAD/CAM, etc, and 3D printing, and all of that. That is a discussion that happened and that was important, and that is continuing to impact the production of architecture and the teaching of architecture. Because now, the possibility of a student making prototypes, physical prototypes out of their projects is much stronger than before. That set of tools and equipment have entered into the workshop and even into the studio space. Behind every student, sometimes you find a 3D printer.

We are beginning to discover that they are not contingencies at all, but they are crucial to the shaping of architecture.

So the presence of this new technology and industry is in the studio. But another level, I think, which is going to be even more important is the possibilities that these technologies are bringing, to changing what we consider to be contingencies or externalities to the design process and what we don't. For the past century, I would say, we have come to acknowledge that the important factors in the design project are the form of composition and the arrangement of space—structure to a secondary level, but ultimately, it's all about the composition.

And that factors like context, not always, but sometimes factors like the mechanical, electrical, the environmental budget constraints are seen as contingencies or as secondary or tertiary factors of the building. The technologies that we have right now allow us to have all of these factors built into the design-making from the get-go. And all of a sudden, I think, we are beginning to discover that they are not contingencies at all, but they are crucial to the shaping of architecture.

The performance of a system is difficult to measure because the discrete nature of the architectural object allows us to contain it, to fathom it, to measure it, to assess it.

And especially with the sustainability pressures on us, we have to rise to the responsibility and to the occasion. And therefore we are beginning to even strengthen the capacity and the agency of the architect as a synthesiser, of all of these factors together, thanks to this new technology. This is a direction that I'm hoping we can see, improve, and change the profession by changing the education of the architect.

Greg: It's interesting. I'm reminded of a line by Frank Duffy, the office architect who once asked whether architects were slaves at the mill in the sense that they were bound to a system that led inexorably to the production of physical space, whether that space was needed or not. And it's interesting, because your Biennale raises particular questions about—it looks at some of the issues beyond simply that amount of space.

And I'm curious about what directions architecture should head in beyond simply that construction of space to look at these relationships, these contingencies, and ways to reconfigure the system of how we produce the built world, and if that opens up particular avenues on the other side of this, that could lead the profession interesting ways.

Hashim: That is definitely in this Biennale, but also in the air among young architects—the interest in going beyond designing objects to designing systems. Now, that's very challenging, because systems are sometimes invisible, and how do you design them? The aesthetic evaluation of the system is very hard. We know what is a beautiful object, or at least we dabble with the qualities that we think are describable as beautiful or not. But a system is a tough thing to measure that way.

In the air among young architects [is] the interest in going beyond designing objects to designing systems. That's very challenging because systems are sometimes invisible, and how do you design them?

More importantly, the performance of a system is difficult to measure, because the discrete nature of the architectural object allows us to contain it, to fathom it, to measure it, to assess it. But a system depends on so many other factors and variables, and indeterminate futures, that it becomes very difficult for us to assess. But we're beginning to take on this challenge and introduce it into our thinking.

Obviously, by system, we mean environmental systems, the urban system, the connectivity of the object, or the architectural intervention to a larger network in which, to which it belongs. And its impact on it is going to be important, but it's very difficult to measure it right now. We're entering into that space and you can see that in the Biennale.

Greg: Indeed, and I mean, it gets to the heart of so many of the wicked problems that confront the world, climate change being one of them obviously—and a world perhaps of, yes, of mounting adversity and diminishing resources in some areas. Pivoting to an example of that, I wanted to ask you about Beirut, obviously, as a Lebanese architect. And we've had a prior episode looking at the destruction of Beirut and the challenges the city and the nation of Lebanon will face given the collapse of its economy over the last year.

I'm curious about how you would intervene there and where there might be spots for intervention and in the context of so much of the city has to be rebuilt. So much wealth has been destroyed because of currency issues. How again, does sort of design intervene or find spots to begin that process given so many systems in perhaps freefall right now? I'm curious how you look at that problem and think, where can we begin to solve that?

Hashim: The explosion that happened in Beirut last August happened at about one kilometre away from the city centre in the harbour of Beirut. The past reconstruction of Beirut in the 1990s was in the old downtown—a downtown that was historically very vitally linked to the harbour. But over the years of the reconstruction, and for, because of the privatisation of the process of reconstruction, and the not so friendly relationship between the port and the company that took control of the reconstruction, the harbour was separated from the downtown. That created a rupture in the fabric of the city that till today we feel. That downtown is sitting in the middle but without that vital economic connection.

The explosion made us aware of the proximity between the harbour and the residential areas of Beirut in the downtown. And it made us, as we are beginning to rethink the reconstruction of the harbour and the areas around it, aware of the possibilities of reconnecting the two.

In the meantime, the harbour grew on its own because of container shipping and other needs and isolated itself even further from the residential area that was behind it, and even from the transportation networks that fed it originally. The explosion made us aware of the proximity between the harbour and the residential areas of Beirut in the downtown. And it made us, as we are beginning to rethink the reconstruction of the harbour and the areas around it, aware of the possibilities of reconnecting the two. The opportunities for Beirut are to correct the mistakes of the previous reconstruction by connecting the economic vitality of the cities with its residential fabric and with its commercial centre. That's where I feel we should put our emphasis.

Greg: Interesting. Well, as a last question, I want to return to the Biennale. It's been interesting in terms of the arc of the Biennales over the last decade from, you know, Aaron Betsky's show very focused on form. There was a turn with curators such as Alejandro Aravena, who of course is also in your Biennale, to explore some of these pressing social issues. And I thought it was interesting at the time it was announced, that your theme of "How will we live together?", followed quite naturally from Freespace under the previous curators, of looking at these rethinking of social relationships.

And looking ahead, you know, any advice you might have for future curators or thinking about where the Biennale should go? What are the questions that should grapple with on the other side of it? What is the larger story that you have provided a chapter in that the Biennale has tried to tell and how the Biennale can be a force for thinking through these issues? Because of course, its critics argue that the Biennale is, you know, a party for architects, a wasteful exercise, etc. But it's, you know, unlike any other event in its ability to convene, so what should we be convening for?

Hashim: Every field, every discipline, every profession should have its parties. And the poor profession of architecture doesn't have that many. So Venice has, since the 80s, provided that opportunity for architects to come together to discuss and show what possibilities they are thinking about for the future. That's hugely important. And that proved to be the case, when everybody converged on Venice for the opening of the Biennale.

There were 7,000 people who were there, usually there were 12,000 on the opening weekend. There were 7,000 on this one, just one week after the borders opened in Europe. This proves that people were really interested in coming together, seeing what young architects from around the world are proposing, trying to do, and benefiting from this to have discussions about the future of architecture. These are irreplaceable and the platforms that the Venice Biennale, but also other Biennales provide, is hugely important.

Venice has the experience, has the space, has the visibility. And that's what we benefited from in being able to turn around and make a Biennale happen despite all of the financial, travel, and public health constraints. So yes, there are sometimes continuities among Biennales, but then there are sometimes ruptures. A part of that is the decision of the president of the Biennale in terms of who they appoint as curator, but a part of that is also the decision of the curators themselves in choosing the theme.

It is part of the Biennale's mission as well is to surprise us, to introduce different angles on architecture from different periods.

There are clearly strong continuities, as you observe, in terms of the relation between this Biennale and past Biennales, particularly when it comes to Aravena's Biennale on the social dimension, particularly when it comes to the very early or kind of forerunners of the Biennales by Vittorio Gregotti in terms of the relationship with the territory and landscape. There's a lot of territory and landscape and planet here. When it comes to where the future of the Biennale lies, I am so happy that it's not my responsibility to determine. But I also feel that it is part of the Biennale's mission as well is to surprise us, to introduce different angles on architecture from different periods.

Invariably, Greg, the Biennale is a kind of time capsule that tries to capture the situation, at the moment, at its best, both in terms of what its problems are, and what it could propose as being inspiring projects and possibilities for architecture.

There are Biennales that have been much more reflective on the present condition and even on the past. And by that I point to Demetri Porphyrios'—uh, sorry—the first Biennale, the, "The Presence of the Past". But I feel like some Biennales try to represent the moment at its best through built projects. This Biennale is not about that. It does include built projects. It does include projects that are proven to be valid and deployable like the two more projects that I mentioned earlier. But it also includes research. It includes theoretical propositions, experiments, and widely visionary projects. This Biennale is about the future.

Greg: Thank you, Hashim.

This episode was directed and produced by myself, Alexandra Siebenthal and Radka Ondrackova and with support from Martin Barry, Nikkolas Zellers, Weronika Koleda, and Anna Stava, as well as Nano Energies and the Czech Ministry of Culture. It was edited by LittleBig Studio.

More Venice Biennale curators featured in this episode:

Venice Architecture Biennale Nordic Pavilion: What We Share with Siv Helene Stangeland + Reinhard Kropf

reSITE is back with a special two-part Design and the City episode covering the long-awaited Venice Architecture Biennale to explore the question “How will we live together?” We spoke with exhibitors of the Nordic Pavilion, Siv Helene Stangeland and Reinhard Kropf, entitled What We Share about the inspiration behind their co-living experiment in Stavanger, Norway, which they not only designed, but also occupy, along with 65 other tenants.

Venice Architecture Biennale U.S. Pavilion: American Framing with Paul Andersen + Paul Preissner

reSITE is back with a special two-part Design and the City episode covering the long-awaited Venice Architecture Biennale to explore the question “How will we live together?” Part-one covers the U.S, Pavilion curators, Paul Andersen and Paul Preissner as they reexamine humble softwoods and their place as the literal bones for American homes in their exhibition entitled “American Framing”.

Venice Architecture Biennale: How Will We Live Together? [Part 1]

reSITE is back with a special two-part Design and the City episode covering the long-awaited Venice Architecture Biennale to explore the question “How will we live together?” Part-one covers the U.S, Nordic and Luxembourg Pavilion curators for their use of timber and wood construction to answer this years pressing question.

Venice Architecture Biennale: There Are Walls That Want to Prowl, Lukas Feireiss + Leopold Banchini

reSITE is back with a special two-part Design and the City episode covering the long-awaited Venice Architecture Biennale to explore the question “How will we live together?” with curators Lukas Feireiss and Leopold Banchini to discuss their definitions of shelter, application of wood structures, degrowth models and retrospectives to rethink how we will live together.

More from Design and the City

Trey Trahan on Building Sacred Spaces for Connection

This episode of Design and the City features the founder of Trahan Architects, Trey Trahan on the importance of creating sacred spaces devoid of clutter that make way for that human connection, his definition of beauty, and the potential regeneration holds, presenting a different side of that coin.

Tim Gill on Building Child-Friendly Cities

A city that is good for children, is good for everyone--and idea we explore with Tim Gill, author of Urban Playground: How Child-Friendly Planning and Design Can Save Cities, on this episode of Design and the City. Photo by Els Lena Eeckhout.

Why is Birth a Design Problem with Kim Holden

Can rethinking and redesigning the ways birth is approached shift the outcomes of labor and birth experiences? Can it be instrumental in improving our qualities of life--in our environments, in cities, and beyond? Architect and founder of Doula x Design Kim Holden join Design and the City to explore how she sees birth as a design problem. Photo by Kate Carlton Photography

The Architecture of Healing with Michael Green + Natalie Telewiak

Michael Green and Natalie Telewiak love wood. These Vancouver-based architects champion the idea that Earth can, and should, grow our buildings--or grow the materials we use to build them on this episode of Design and the City. Photo courtesy of Ema Peter